Table of Contents

Introduction

This is one of the most frustrating situations leadership teams encounter.

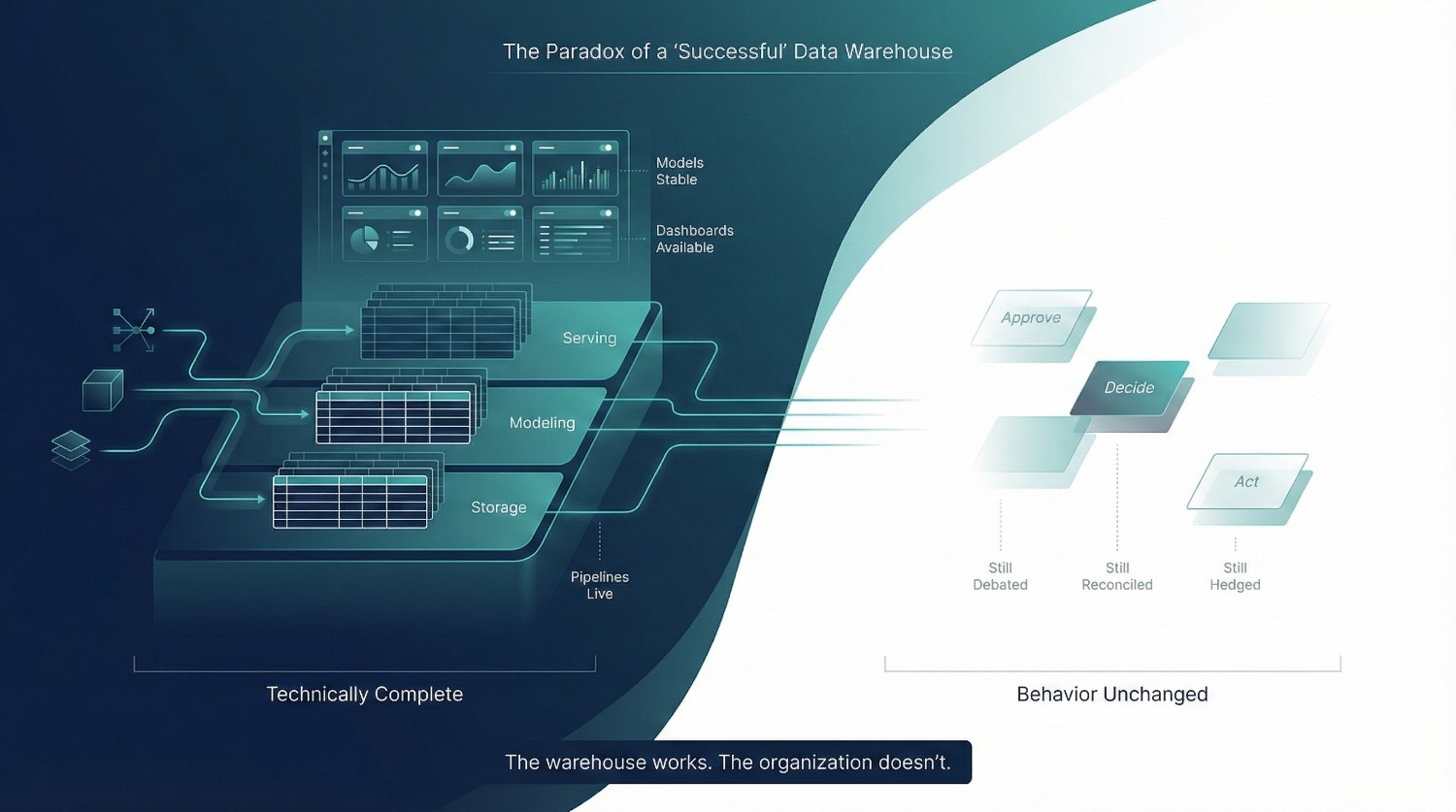

On paper, everything looks right.

- A modern cloud data warehouse is live

- Pipelines run reliably

- Models are clean and performant

- Tooling is current and well chosen

The technical checklist appears complete. In modern cloud data platforms, technical completeness is no longer rare. With mature managed services, reference architectures, and experienced talent, it is entirely possible to deliver a warehouse that is fast, stable, and well modeled, without changing a single decision making behavior in the business.

This is not a failure of engineering. It is a mismatch between what technology can deliver and what organizations are structurally prepared to adopt.

And yet:

- Business teams still don’t trust the numbers

- Adoption stalls or quietly declines

- Decisions continue to rely on spreadsheets and side reports

- Leadership starts asking, “What did we actually get from this?”

From the outside, it feels irrational.

From the inside, it feels familiar.

The Paradox of “Successful” Data Warehouse Projects

Many data warehouse consulting engagements reach technical completion and still feel like failures from a business perspective.

Not because anything is broken, but because nothing meaningfully changed.

- Reporting exists, but isn’t relied on

- Metrics are available, but still debated

- Data is centralized, but decisions remain fragmented

The organization invested heavily, followed best practices, hired capable engineers or consultants, and yet the outcome feels underwhelming.

This is not an edge case.

This pattern has become common enough that major data platform vendors now emphasize operating models, ownership, and adoption readiness alongside performance and scale. Snowflake, Databricks, and Google Cloud increasingly frame successful analytics programs as organizational transformations, not platform deployments.

Yet many consulting engagements still scope, staff, and measure success almost entirely through technical delivery.

Why This Failure Is So Confusing

Traditional explanations don’t hold up.

It’s usually not:

- A tooling problem

- A performance problem

- A skills gap

- A lack of effort

In fact, these failures often happen precisely because the technical execution was strong.

The harder the team pushes on delivery, the more visible the gap becomes between what was built and how the organization actually works.

The Real Question Leaders Ask (Often Quietly)

When this happens, leadership rarely says it out loud, but the question is always the same:

“Why didn’t this change how we operate?”

Why are:

- Meetings still spent arguing over numbers?

- Analysts still reconciling instead of analyzing?

- Engineers still fielding questions about meaning and scope instead of building forward?

- Executives still hedging decisions with caveats?

At this point, data warehouse consulting itself starts to feel suspect, not because the work was wrong, but because the promised impact never materialized.

Core Thesis

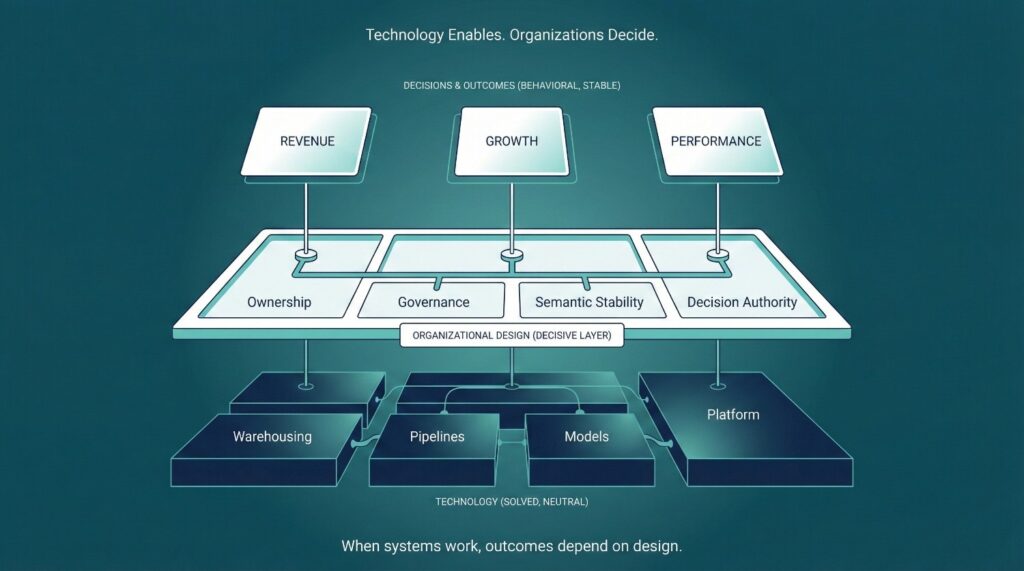

This article makes a clear claim:

Data warehouse consulting fails not because the technology is wrong, but because the organization is unprepared to absorb it.

When:

- Ownership is unclear

- Decisions are deferred

- Semantics are unstable

- Operating models are missing

- Trust is often treated as a side effect….

Even the best technical systems will fail. Data platforms do not fail at scale because they are wrong. They fail because organizations underestimate how much clarity, ownership, and behavioral change is required to make shared data operational.

Until those conditions exist, even the best warehouse will function as a reporting layer, not a decision system.

The warehouse works.

The organization doesn’t.

What This Article Will Unpack

This is not another list of technical best practices.

Instead, we will examine:

- Why strong technical delivery often exposes organizational gaps

- How data warehouse consulting quietly fails after go live

- Where responsibility shifts from engineers to leadership

- What must be in place before technology can create value

If you’ve ever wondered why a “successful” data warehouse still feels like a disappointment, this article will explain why, and what has to change for it to actually work.

The False Definition of “Success”

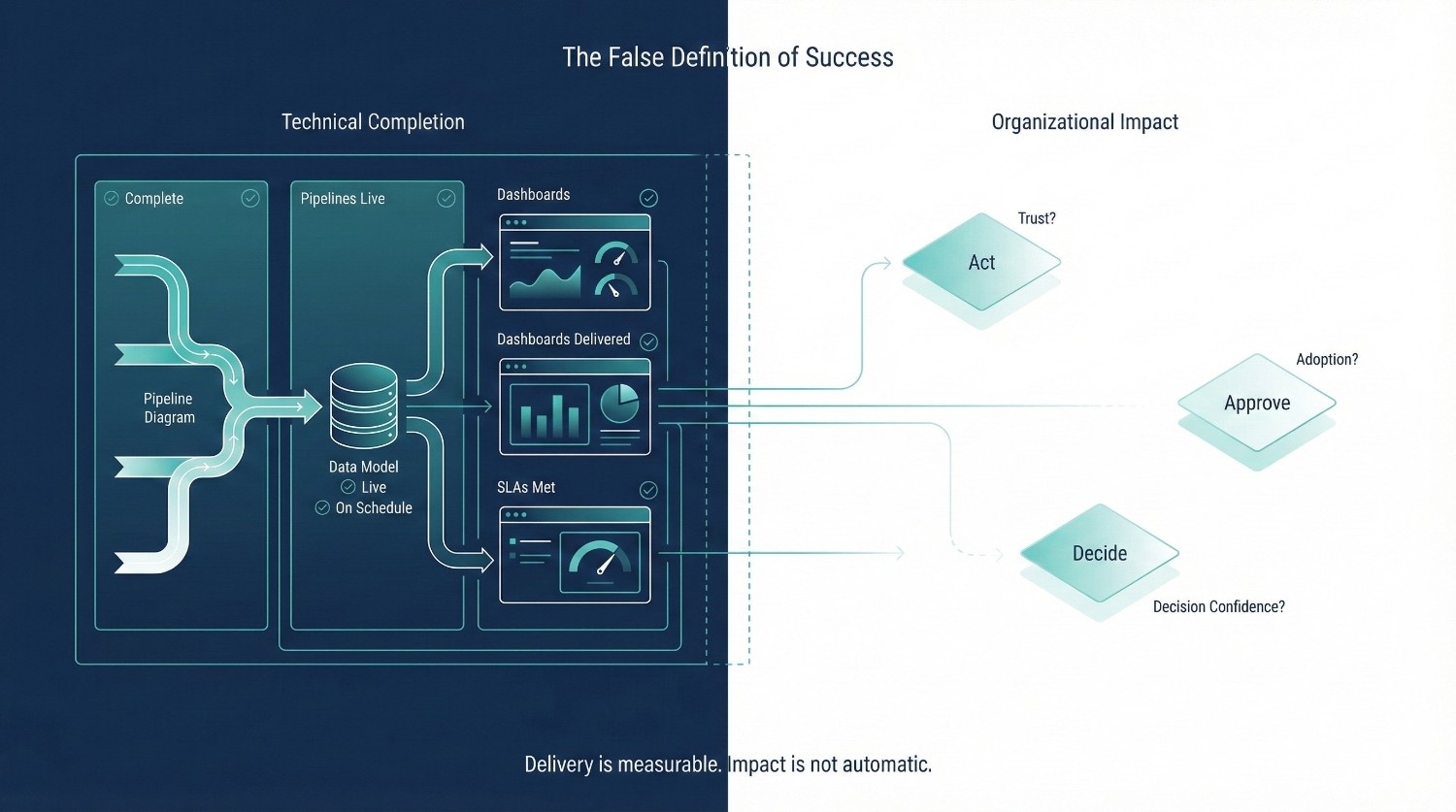

One of the biggest reasons data warehouse consulting underdelivers, even when the technology is solid, is that success is defined too narrowly.

The work finishes.

The system runs.

The engagement is closed.

And yet, the organization feels unchanged.

That disconnect comes from confusing technical completion with organizational impact. Narrow success metrics persist because they are easy to contract, easy to report, and easy to defend. Delivery milestones fit cleanly into project plans, statements of work, and steering committee updates.

Organizational impact is harder to measure, it requires tracking behavior change, decision confidence, and accountability, which most engagements are neither scoped nor incentivized to own.

Technical Completion vs. Organizational Impact

Technical teams and consultants often declare success primarily based on delivery milestones.

From a delivery perspective, this makes sense:

- Pipelines are running

- Models are built

- Dashboards are live

- SLAs are being met

But none of these guarantee that decisions have improved.

Pipelines Running ≠ Decisions Automatically Improved

A pipeline can be perfectly reliable and still feed:

- Ambiguous metrics

- Conflicting definitions

- Data no one feels confident using

If decision makers still ask for manual checks or alternative numbers, the pipeline is infrastructure, not value. Infrastructure becomes leverage only when it replaces existing decision mechanisms. If spreadsheets, side reports, and manual reconciliations still exist in parallel, the warehouse has not failed, it has simply not displaced anything.

Dashboards Shipped ≠ Trust Earned

Dashboards are relatively easy to launch and notoriously hard to adopt.

If:

- Numbers surprise users

- Definitions aren’t understood

- Changes aren’t explained

- Ownership isn’t clear

Then dashboards become reference material, not decision tools.

Organizational impact shows up when people stop questioning whether the data is safe to use.

How Consulting Success Is Mis-measured

Most consulting engagements are measured on what is easiest to track.

Common success signals include:

- Tickets closed on time

- Models deployed to production

- Dashboards delivered as scoped

- SLAs met for freshness and uptime

These metrics are not wrong, but they are insufficient on their own.

They measure activity, not outcomes.

They answer:

- Was the work done?

- Was it delivered as promised?

- Did the system behave as expected?

They do not answer:

- Did decision making change?

- Did trust improve?

- Did adoption increase?

- Did ambiguity decrease?

When these deeper questions are never asked, disappointment is inevitable.

Why These Metrics Are Dangerously Incomplete

The danger is not that technical metrics exist.

The danger is that they become the only definition of success.

When success is framed this way:

- Consultants optimize for delivery, not adoption

- Engineers ship quickly rather than carefully

- Ambiguity gets encoded instead of resolved

- Hard conversations are postponed until “after go live”

Ambiguity hardens once systems are live. Teams adapt around uncertainty, build workarounds, and normalize exceptions. By the time leadership intervenes, fixing ownership and semantics is no longer a technical task, it is an organizational change problem.

By the time leadership realizes value hasn’t materialized, the engagement is over and the system is already in use.

At that point:

- Ownership gaps are harder to fix

- Semantic drift is entrenched

- Business teams have formed opinions

- Trust debt has accumulated

All while the project is officially labeled “successful.”

The Core Problem

Data warehouse consulting often disappoints because it succeeds on paper.

The technology works.

The checklists are complete.

The engagement closes cleanly.

But the organization never changed how it:

- Defines metrics

- Resolves disputes

- Makes decisions

- Trusts data under pressure

Until success is measured by those outcomes, not just by delivery artifacts, data warehouse consulting will continue to feel underwhelming even when the tech is right.

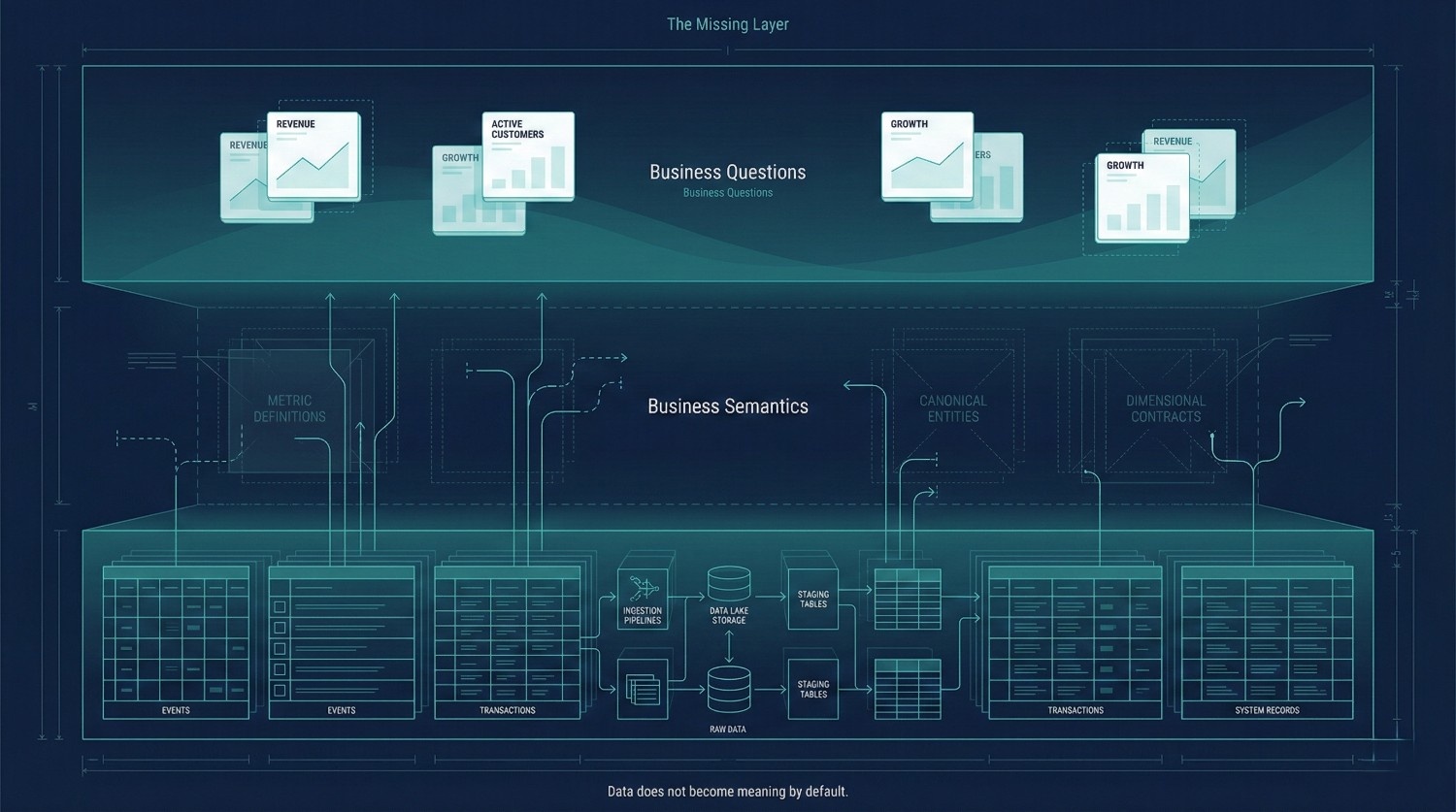

The Missing Layer

When data warehouse consulting “fails” despite solid technology, the missing piece is very often the same:

Business semantics were never truly established.

The warehouse contains data.

It does not automatically contain meaning.

And without meaning, organizations struggle to trust or reuse what they’ve built.

Raw Data ≠ Meaning

Raw data answers system level questions:

- What event was logged?

- What value was stored?

- When did a record change?

Business users ask decision level questions:

- How much revenue did we generate?

- How many active customers do we have?

- Are we performing better than last quarter?

These are not the same questions.

A technically correct warehouse can faithfully represent raw events and still fail to answer business questions consistently, because meaning is not inherent in the data. It has to be designed. In mature analytics organizations, semantics are treated as a first class design artifact, alongside schemas and pipelines. This includes explicit metric definitions, dimensional contracts, and documented decision logic that remains stable even as underlying data sources change.

This translation layer is where many consulting efforts quietly fall short.

Why Semantic Modeling Is the Real Consulting Work

This is also the layer internal teams often struggle to establish on their own. Semantic decisions cut across teams, incentives, and historical assumptions, making them difficult to resolve without external facilitation and authority. When consulting avoids this layer, it avoids the very work organizations hire consultants to help with.

Semantic modeling is where consulting effort most often creates lasting value.

It is the work of:

- Defining canonical entities (customer, order, subscription, event)

- Establishing metric definitions that hold under pressure

- Choosing one interpretation when multiple are reasonable

- Encoding business logic once, so it doesn’t have to be reinvented everywhere

This work is difficult because it forces decisions that organizations often avoid:

- Which definition wins when teams disagree?

- Which edge cases matter?

- Which historical inconsistencies are acceptable?

- Who owns the answer when numbers are questioned?

Consulting that stays focused on pipelines and performance often avoids this discomfort, and that avoidance is a major reason systems fail to land.

Common Failure Modes When Semantics Are Weak

When the semantic layer is underdeveloped or ignored, the same problems surface again and again.

Ambiguous Metrics

Metrics like “revenue,” “active user,” or “conversion” exist, but with caveats.

Different teams:

- Apply different filters

- Use different time windows

- Include or exclude edge cases differently

The metric has a name, but not a stable meaning.

Inconsistent Dimensions

Dimensions such as customer, product, or region appear consistent, but behave differently across reports.

A “customer” in one dashboard:

- May include inactive accounts

- May exclude test users

In another, it may not.

These inconsistencies aren’t bugs, they’re symptoms of missing semantic contracts.

Unowned Definitions

No one is accountable for answering:

- “Is this the correct number?”

- “Why did this change?”

- “Which definition should we use going forward?”

When definitions have no owner, every disagreement becomes political, and every resolution is temporary.

The Result: Regression to Old Habits

When business semantics are unclear, business behavior adapts predictably.

Business teams:

- Export data to spreadsheets

- Rebuild logic locally

- Maintain “backup” reports

- Trust their own numbers over the warehouse

Parallel logic emerges again, not because people are stubborn, but because the system feels unsafe to rely on. From a business perspective, spreadsheets are not a rebellion against the warehouse, they are a risk management tool. When definitions shift silently or ownership is unclear, local logic feels safer than shared ambiguity.

At that point, the warehouse is technically successful but organizationally irrelevant.

Why This Is a Consulting Failure, Not a Business Failure

Business teams revert to spreadsheets when:

- Meaning changes without warning

- Numbers require explanation before use

- Accountability is unclear

That behavior is rational.

The failure lies in data warehouse consulting that:

- Treated semantics as secondary

- Avoided decision ownership

- Optimized for delivery speed

- Assumed meaning would “sort itself out”

It never does.

Semantic modeling is not an enhancement layer.

It is the layer that determines whether data can be used without negotiation.

Until data warehouse consulting treats business semantics as the primary work, technically correct systems will continue to be quietly abandoned after launch, even while every dashboard still loads perfectly.

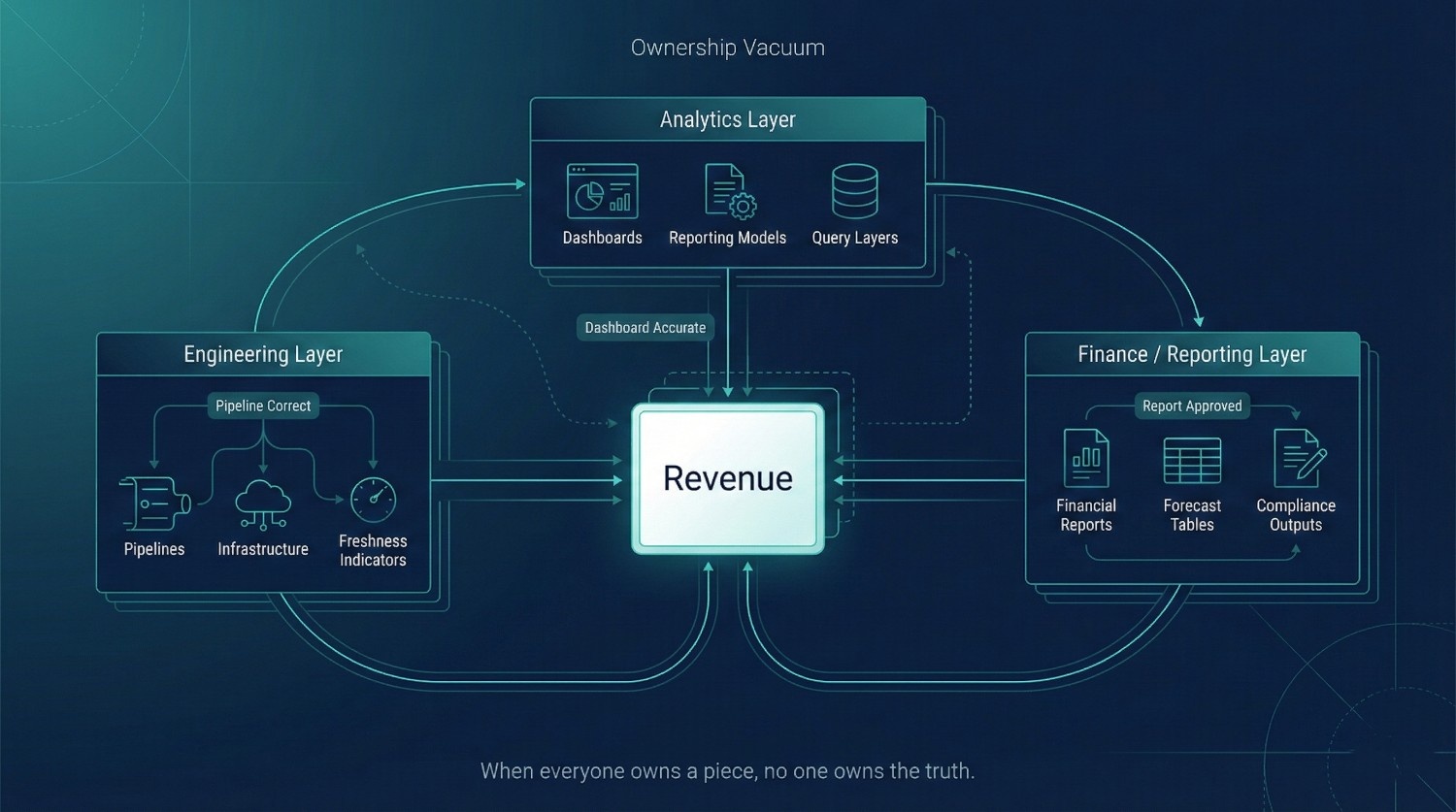

Ownership Vacuum

In practice, underperformance in data warehouse consulting is rarely technical, it is rooted in unclear ownership.

Everyone owns a piece of the system.

No one clearly owns the truth it produces.

Fragmented Ownership Is the Default

Ownership of data is often misunderstood as a reporting line or a role assignment. In practice, ownership means decision rights: who can define a metric, approve changes, and stand behind the number when it is challenged.

Without explicit decision authority, ownership exists in name only.

In most organizations, ownership looks like this:

- Engineering owns pipelines

Reliability, performance, freshness, cost. - Analytics owns dashboards

Queries, reports, visualizations, stakeholder requests. - Finance owns reporting

Revenue numbers, forecasts, compliance facing outputs.

Each role is legitimate.

Each role is doing its job.

And yet, when numbers are questioned, no one can say:

“This is the authoritative answer, and I’m accountable for it.”

That gap is where trust reliably erodes.

When Everyone Owns Something, No One Owns Truth

In an ownership vacuum:

- Engineers say, “The pipeline is correct.”

- Analysts say, “That’s what the model outputs.”

- Finance says, “This doesn’t match what we reported.”

- Leadership asks, “So which number do we use?”

There is no clear escalation path because truth itself has no designated owner.

As a result:

- Disputes become political instead of resolvable

- Decisions stall while numbers are debated

- Changes are delayed because no one has authority to approve them

- Engineers become accidental arbitrators of meaning and definition

Engineers are pulled into semantic disputes not because they are best positioned to resolve them, but because they are closest to the system. This creates a failure mode where technical teams absorb organizational ambiguity, slowing delivery and eroding trust on all sides.

Why Data Warehouse Consulting Consistently Struggles Without Ownership

Data warehouse consulting depends on decisions being made and upheld over time.

Without ownership:

Disputes Escalate

Every disagreement travels upward, to managers, directors, executives, because there is no designated owner empowered to decide.

Over time, leadership loses patience and confidence.

Changes Stall

Even small changes feel risky:

- “Who approved this?”

- “What will it break?”

- “Can we revert it?”

So teams freeze. Temporary workarounds become permanent. Progress slows quietly.

Trust Erodes Quietly

The most dangerous part is that erosion happens silently.

Business teams adapt by:

- Keeping their own numbers

- Adding manual checks

- Maintaining shadow reports

- Trusting the warehouse less, not more

No outage occurs.

No incident is logged.

But adoption fades.

Ownership failures rarely trigger alarms. Systems remain up, dashboards load, and SLAs are met. The damage shows up instead as hesitation: decisions deferred, caveats added, and reliance shifted elsewhere.

By the time leadership notices, trust has already moved on.

Why This Is a Consulting Failure

When data warehouse consulting avoids ownership questions, it sets the system up to fail after going live.

Consultants often:

- Deliver clean models

- Document definitions

- Recommend governance

But if ownership is not explicitly assigned and operationalized, those artifacts have no authority.

A definition without an owner is a suggestion.

A model without ownership is optional.

The Hard Truth

A data warehouse can only be trusted if:

- Someone is accountable when numbers are challenged

- Someone has authority to approve changes

- Someone is responsible for long term semantic stability

Without that, the warehouse becomes a shared resource with no steward, and shared resources without stewards predictably decay over time.

Data warehouse consulting doesn’t fail because engineers didn’t build well.

It fails because the organization never answered the simplest, and hardest, question:

Who owns the numbers when it actually matters?

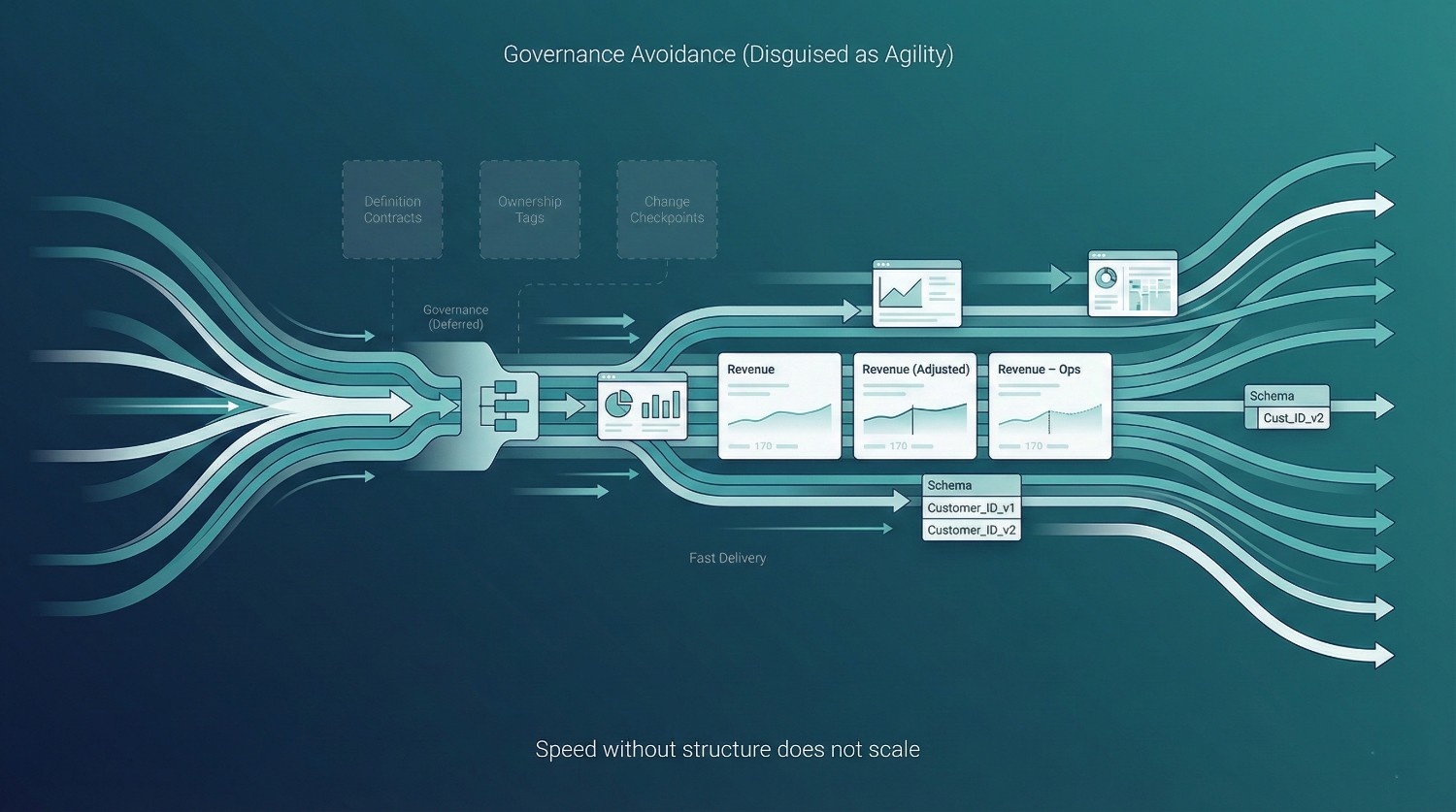

Governance Avoidance (Disguised as Agility)

Few things undermine data warehouse consulting more quietly than this phrase:

“We don’t want bureaucracy.”

It sounds reasonable.

It often signals deeper structural risk.

In many organizations, governance is avoided in the name of speed and flexibility. What often actually follows is not agility, it’s unbounded drift.

“We Don’t Want Bureaucracy”

This belief usually comes from real pain. Resistance to governance is rarely ideological. It is usually a reaction to governance models designed for control rather than flow. When governance slows delivery, obscures accountability, or exists only as documentation, teams learn to avoid it, even when structure would help.

Teams have experienced:

- Slow approval processes

- Overly rigid standards

- Committees blocking progress

- Governance that exists only in documents

So they swing hard in the opposite direction.

No rules.

Unclear owners.

Informal approvals.

“We’ll figure it out as we go.”

For a short time, this feels fast.

Governance Deferred Indefinitely

In practice, governance isn’t removed, it’s postponed.

Decisions are avoided with phrases like:

- “Let’s keep it flexible for now”

- “We’ll standardize later”

- “This is just temporary”

- “We don’t want to slow delivery”

But data systems rarely stay neutral while decisions are deferred.

They harden around whatever happens first. In data systems, the first acceptable decision often becomes the default standard. Not because it was correct, but because downstream logic, dashboards, and expectations were built around it. Over time, reversing these early choices becomes politically and technically expensive.

Temporary logic becomes permanent.

Local fixes become shared assumptions.

Ambiguity becomes embedded in models.

By the time governance is reconsidered, the cost has usually multiplied.

The Cost of No Rules

When there is no lightweight governance, the same failure patterns appear again and again.

Metric Sprawl

Without clear ownership and definitions:

- Slightly different versions of the same metric appear

- Teams create “their own” versions for safety

- Leadership sees conflicting numbers with similar names

Individually, every metric is justified. Together, they create noise.

Schema Drift

Drift does not occur because teams are careless. It occurs because systems amplify small inconsistencies when there is no mechanism to resolve them. Without governance, variation compounds faster than alignment.

Without change control:

- Columns change meaning over time

- New fields are added without context

- Old logic lingers even when assumptions change

The schema still works, but it no longer tells a consistent story.

Conflicting Logic

When there are no shared contracts:

- Business logic moves into dashboards

- Analysts rewrite filters independently

- Engineers encode assumptions defensively

At that point, correctness becomes subjective, and trust collapses.

Why This Feels Like Agility (But Isn’t)

Avoiding governance feels agile because:

- Work moves quickly at first

- No one is blocked

- Decisions don’t require alignment

The absence of constraints feels liberating early on. But without shared contracts, every downstream change requires explanation, validation, and negotiation. What looked like speed becomes a coordination tax, paid repeatedly.

Agility without structure doesn’t scale.

Sustained agility is not the absence of rules, but the presence of:

- Clear contracts

- Predictable change

- Fast resolution of disagreement

Without those, every change requires re-validation, re-explanation, and re-negotiation. The system slows down, not because of rules, but because of uncertainty.

Why Lightweight Governance Is Not Optional

The alternative to heavy governance is not no governance.

It is embedded, lightweight governance.

Effective data warehouse consulting introduces governance that:

- Assigns owners, not committees

- Documents definitions, not policies

- Controls change through workflow, not meetings

- Makes the right path the easy path

This kind of governance:

- Speeds up delivery over time

- Reduces rework

- Prevents silent drift

- Protects trust

The most effective governance is embedded directly into workflows: code reviews enforce definitions, deployment paths encode ownership, and change logs explain intent. When governance lives where work happens, it stops feeling like overhead. Most importantly, it makes the warehouse safe to use.

Data warehouse consulting underdelivers when governance is treated as an enemy of speed.

In reality, governance is what allows speed to compound instead of resetting.

Without it, agility is temporary, and the cost shows up later as confusion, rework, and lost confidence, even when the technology itself is working perfectly.

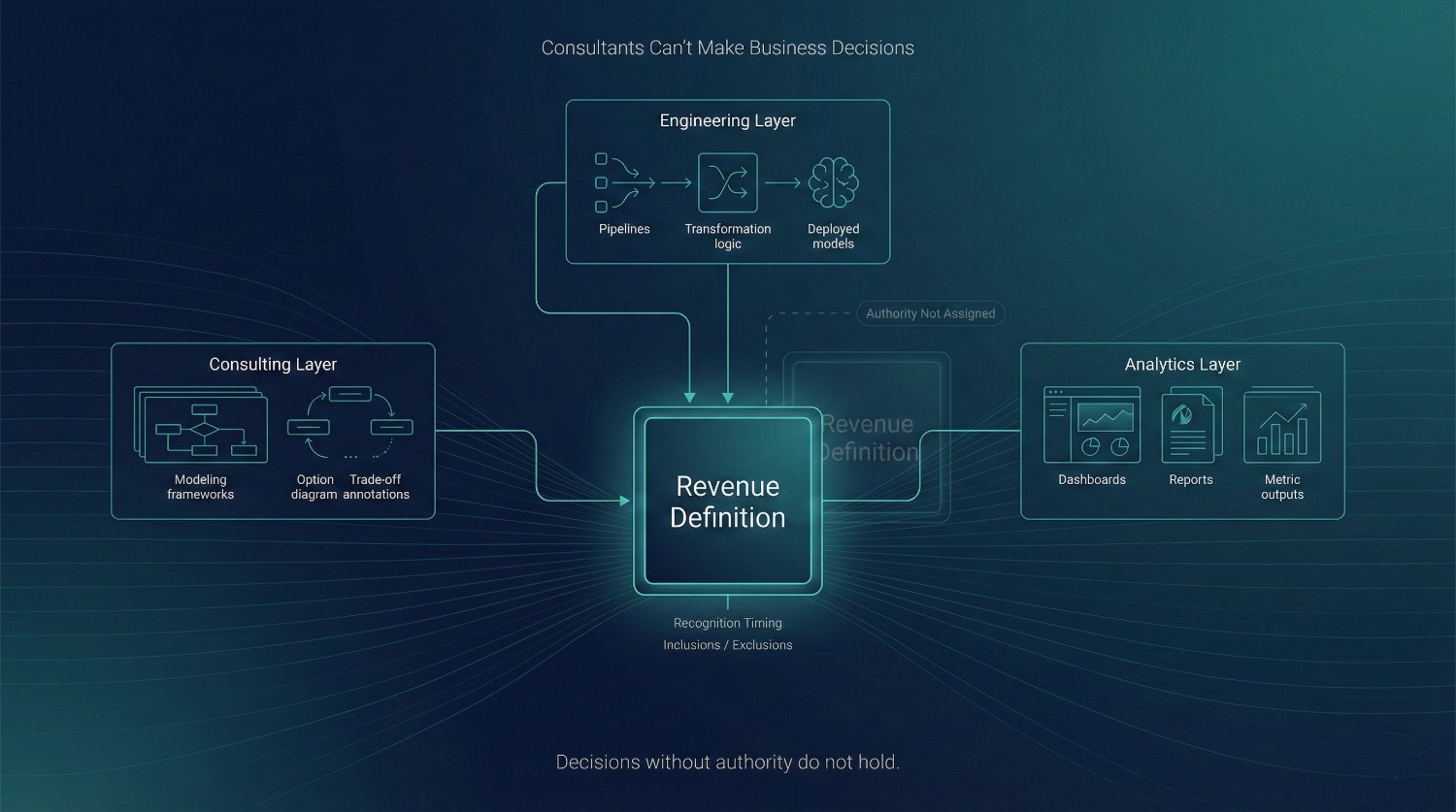

Consultants Can’t Make Business Decisions

One of the most predictable failure points in data warehouse consulting appears when consultants are implicitly expected to do one thing they cannot do: make binding business decisions.

This expectation is rarely stated directly. It emerges gradually through deferred escalations and open ended questions. Leadership wants momentum, teams want closure, and consultants, often the only ones present across all domains, become the path of least resistance.

Asking them to “just decide” feels expedient at the moment, but it is an improper transfer of organizational responsibility.

The Decisions Consultants Are Often Asked to Make

As migrations progress, ambiguity surfaces. At that point, consultants are frequently asked to:

- Define revenue

Decide which transactions count, when revenue is recognized, and how edge cases are treated. - Resolve historical inconsistencies

Choose whether old numbers should be corrected, preserved, or versioned, and how to explain changes. - Choose winners between teams

Pick one definition over another when Product, Finance, and Sales disagree.

On the surface, this looks like efficiency.

In practice, it is decision abdication.

Why This Always Fails

Consultants can recommend and model options. Designing options is not the same as choosing outcomes. While consultants can frame trade-offs and implications, selecting a definition commits the organization to a narrative that persists long after the engagement ends.

They cannot make those decisions, and when pressured to, the system degrades in predictable ways.

No Authority

Decisions without organizational backing are fragile. They hold until challenged, at which point there is no recognized owner with the legitimacy to defend or enforce them. The system technically remembers the decision, but the organization does not.

No Accountability

When numbers are questioned in executive reviews, consultants are not in the room to defend them. Accountability always returns to internal teams.

No Political Cover

Many data decisions are inherently political. They affect:

- Performance narratives

- Incentives

- Bonuses

- Accountability

Consultants cannot absorb that fallout. Only internal leadership is positioned to do so.

Moreover, the political nature of above mentioned decisions is not a flaw, it is a signal. When metrics affect incentives and accountability, leadership involvement is not overhead; it is the mechanism that makes alignment durable.

The Hidden Cost of Letting Consultants Decide

When consultants are pushed into decision roles:

- Decisions are encoded quietly into models

- trade-offs are undocumented

- Teams feel overruled rather than aligned

- Trust erodes once changes surface

The result is often worse than temporary indecision:

- Numbers change unexpectedly

- Ownership feels external

- Business teams disengage

- Consultants become scapegoats

Why This Is a Consulting Failure, Not a Consultant Failure

This situation arises when data warehouse consulting is treated as decision outsourcing instead of decision facilitation. The highest leverage consulting work is not choosing definitions, it is forcing decisions to be made explicitly, by the right people, at the right time. When that facilitation is successful, technical delivery becomes straightforward.

Good consultants:

- Surface the decision

- Clarify the options

- Explain consequences

- Push for explicit ownership

Bad outcomes happen when organizations:

- Avoid making the decision themselves

- Use consultants as shields

- Hope technical implementation will “settle” disputes

It never does.

The Right Division of Responsibility

In successful engagements:

- Consultants structure and inform decisions

- Leadership makes and owns them

- Engineering implements them

- Business teams validate and adopt them

When these roles are respected, progress accelerates.

When they are blurred, data warehouse consulting stalls, even when the technology is flawless.

Data warehouse consulting does not fail because consultants lack technical skill.It fails because organizations ask them to do what only leadership can:own the meaning and consequences of data.

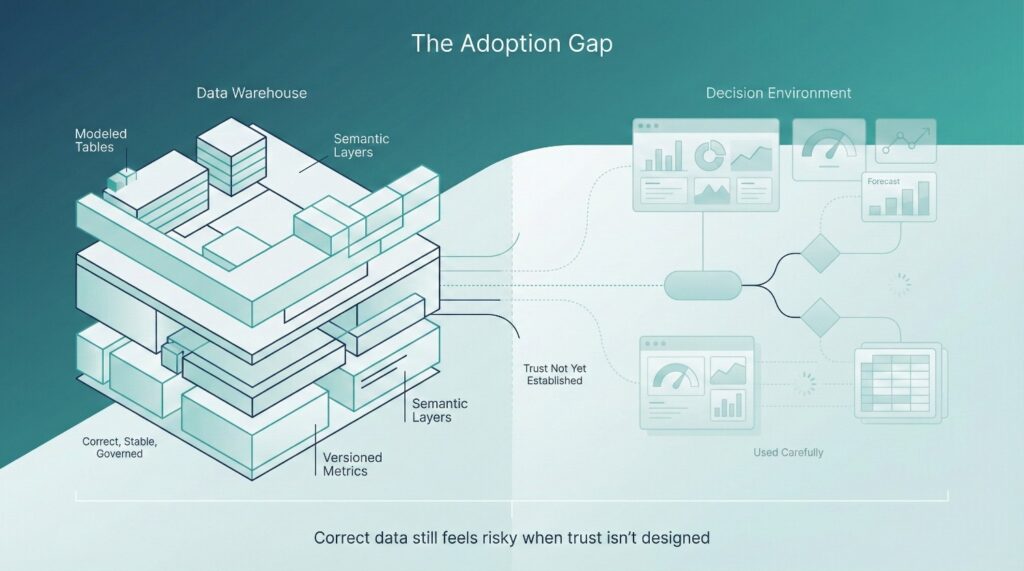

The Adoption Gap

One of the most confusing outcomes of data warehouse consulting is the following:

The system is correct.

The data is accurate.

The models are sound.

And yet, business teams hesitate to rely on it.

From the user’s perspective, adopting a new warehouse is not a technical upgrade, it is a risk decision. Using a new system publicly exposes judgment, accountability, and outcomes. Until that risk feels bound, hesitation is rational.

This is not primarily a failure of engineering.

It is a failure to understand how adoption actually works.

Why Business Teams Resist (Quietly)

Resistance rarely appears as open refusal.

It looks like hesitation, double checking, and fallback behavior.

The most common drivers are:

- Changed numbers

Even when numbers are more accurate, they differ from what people are used to. That difference feels like risk, not improvement. Familiar numbers carry social proof. They have been used before, defended before, and survived scrutiny. New numbers, even better ones, lack that history, making them feel fragile in high stakes settings. - Loss of flexibility

Legacy systems and spreadsheets allow on the fly adjustments. Structured models feel restrictive, even when they are more correct. What feels like flexibility in legacy tools is often ambiguity. Structured models reduce that ambiguity, which improves consistency, but also removes the ability to adjust narratives on the fly. - Fear of exposure

Clean, consistent data makes discrepancies visible. That visibility can surface uncomfortable truths about performance, process gaps, or past assumptions.

Each of these dynamics triggers self protective behavior.

How “Correct” Data Feels Unsafe

From a technical perspective, correctness is a virtue.

From a business perspective, it can feel threatening.

Correct data:

- Removes plausible deniability

- Narrows interpretive wiggle room

- Forces alignment across teams

- Makes errors and inconsistencies visible

For users who are accountable for outcomes, this feels like:

“If I use this and it’s wrong, or just different, I’m exposed.”

So they hedge.

They:

- Cross check with spreadsheets

- Ask for “one more validation”

- Keep parallel reports “just in case”

- Delay using the new system in high stakes decisions

The warehouse is technically successful, and practically sidelined in decision making.

Why Adoption Is Largely Emotional, Not Logical

Adoption is not driven by accuracy alone.

It is driven by:

- Confidence that numbers won’t surprise users

- Assurance that changes will be explained

- Trust that someone will stand behind the data

- Psychological safety in using it publicly

These are emotional conditions, not logical ones.

Data warehouse consulting often fails here because:

- Adoption is treated as training, not trust building

- Communication focuses on features, not reassurance

- Go live is treated as a finish line instead of a transition

Adoption work accelerates after going live, not before it. Early questions, surprises, and edge cases are not signs of failure, they are the moments where trust is either built deliberately or lost quietly.

When users don’t feel safe, they don’t adapt, no matter how correct the data is.

The Hidden Cost of Ignoring the Adoption Gap

When adoption lags:

- The warehouse becomes a reference system, not a decision system

- Business teams revert to old tools

- Data teams spend time reconciling instead of improving

- Leadership questions the value of the investment

All while the technology continues to perform perfectly.

Data warehouse consulting underdelivers when adoption is assumed to be automatic.

In reality, adoption must be earned, deliberately and emotionally.

Until organizations design for trust, reassurance, and safety, not just correctness, even the best built systems will be used cautiously, if at all.

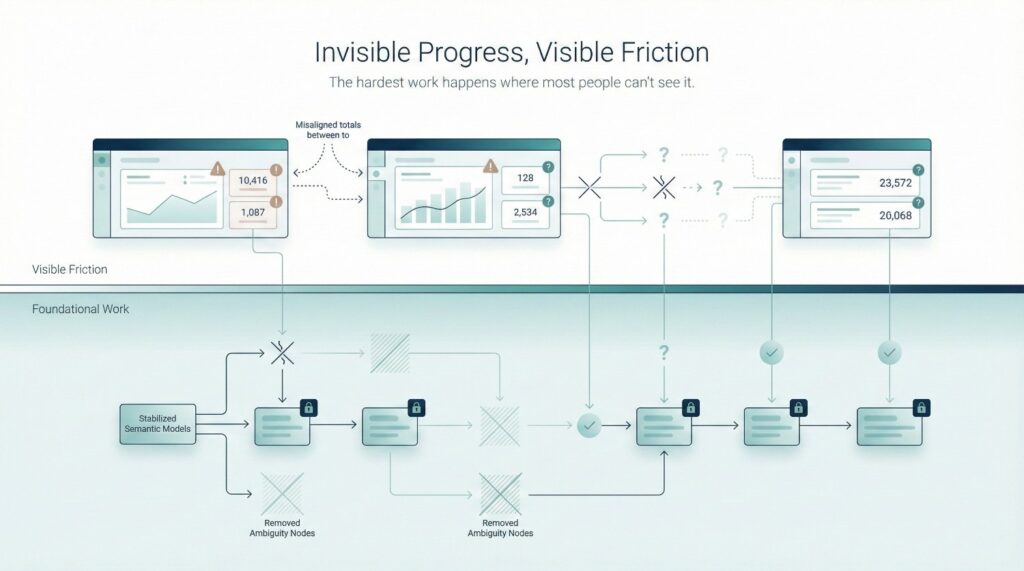

Invisible Progress, Visible Friction

Another reason data warehouse consulting underdelivers, even when the technology is right, is that progress is invisible to the people who matter most.

The hardest work happens below the surface.

The friction shows up where everyone can see it.

Consulting Work Happens Below the Surface

Most consulting effort during a data warehouse engagement is foundational:

- Resolving ambiguous definitions

- Refactoring models to be more stable

- Untangling historical assumptions

- Designing guardrails to prevent future drift

- Validating edge cases that only appear under scrutiny

This work is essential to long term stability yet it rarely produces immediate applause.

That is because it is strictly preventative. It removes future failures, reduces ambiguity, and stabilizes decision paths, outcomes that are only obvious in hindsight, once problems no longer occur.

It is also largely invisible work:

There are no flashy UI changes.

No obvious “before and after” screenshots.

No immediate feature announcements.

From a technical perspective, this is progress.

From a business perspective, it can look like nothing is happening.

What the Business Actually Sees

While foundational work is underway, business teams experience the migration very differently.

They see:

- Delays

“Why isn’t this report ready yet?”

“Why is this taking longer than expected?” - Questions

Requests for clarification, validation, and sign-off that didn’t exist before. - Changed outputs

Numbers that look different, totals that no longer match legacy reports, metrics that require explanation.

To the business, it can feel like the system is becoming harder, not better.

Why This Feels Like Regression

Humans evaluate change relative to familiarity, not correctness. When known imperfections are replaced with unfamiliar rigor, the immediate experience feels worse, even if the long term outcome is objectively better.

From the business point of view:

- Old systems may have been messy, but familiar

- Reports may have been imperfect, but predictable

- Errors were known and managed informally

The new system introduces:

- Precision

- Constraints

- Explicitness

- Accountability

Without context, this feels like friction introduced by the migration itself. Much of this perceived friction comes from surfacing assumptions that were previously implicit. Precision replaces guesswork, and accountability replaces informal tolerance, both necessary shifts, but uncomfortable ones.

So the natural conclusion becomes:

“We had something that worked well enough. Now everything is slower and more complicated.”

That perception is highly damaging.

Why Lack of Narrative Kills Confidence

In the absence of a shared narrative, organizations default to speculation. Narrative acts as a control system: it aligns expectations, explains short term pain, and connects invisible work to visible outcomes.

When progress is invisible, narrative becomes everything.

If there is no clear story explaining:

- What is being fixed

- Why it matters

- What risks are being removed

- When the pain will subside

- What will be better afterward

Then people fill the gap themselves.

And the story they tell is rarely generous.

They assume:

- Consultants are over-engineering

- The team is stuck

- The migration is off track

- The value was overstated

Even when none of that is true.

The Consulting Failure Pattern

Data warehouse consulting often struggles here because:

- Progress is communicated in technical terms

- Updates focus on pipelines and models

- Business impact is implied, not explained

- No one translates effort into outcomes

So confidence erodes long before results are visible.

By the time improvements surface, trust has already been damaged.

The Simple but Rare Fix

Making progress visible does not require exaggeration or premature celebration. It requires translating technical work into business consequences, fewer disputes, faster decisions, reduced rework, and doing so consistently throughout the engagement.

Successful engagements do one thing differently: They make invisible progress visible.

They explain:

- Which decisions are now resolved

- Which ambiguities are gone

- Which future failures have been prevented

- Which questions the business will no longer need to ask

When people understand why friction exists, and what it is buying them, they tolerate it.

When they don’t, every delay feels like failure.

Data warehouse consulting doesn’t fail because progress isn’t happening.

It fails because progress is silent, while friction is loud.

And in the absence of a clear narrative, loud always wins.

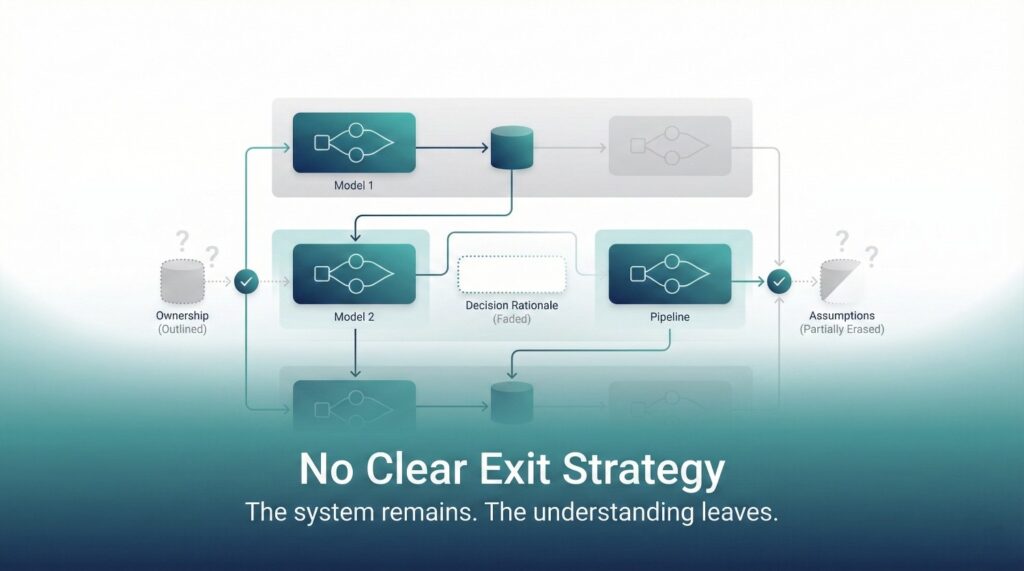

No Clear Exit Strategy

One of the most damaging, and relatively common, failure points in data warehouse consulting appears after the work is declared complete.

The consultants leave.

The warehouse remains.

And the organization quietly realizes it doesn’t fully know how to operate what it now owns.

Consultants Leave

This part is expected. Engagements end. Contracts expire. Teams move on.

But in many failed data warehouse consulting efforts, consultants leave while:

- Key decisions live only in their heads

- trade-offs were never documented

- Governance exists informally

- Context was assumed, not transferred

Nothing breaks immediately, which is what makes this failure so dangerous.

That’s what makes this failure so dangerous.

Knowledge Leaves With Them

When there is no intentional exit plan, the codebase remains, but the context vanishes:

- The Rationale: Why certain models exist is unclear

- The Semantics: Why definitions were chosen is forgotten

- The History: Which edge cases were debated is unknown

- The Risks: Which assumptions are fragile is undocumented

Internal teams inherit a paradox: A technically sound system with invisible reasoning.

Documentation alone is insufficient if it records outcomes without intent. To truly own a system, teams don’t just need to know how it works; they need to know:

- The History: Why specific decisions were made.

- The Graveyard: Which alternatives were rejected and why.

- The Expiration Date: Which assumptions are expected to change over time.

Over time, uncertainty replaces confidence.

Engineers hesitate to refactor.

Analysts avoid core models.

Business teams lose trust when answers can’t be explained clearly.

Internal Teams Inherit Complexity, Without Context or Authority

Complexity is manageable when teams have authority to simplify it. Without decision rights, internal teams default to caution, avoiding refactors, minimizing change, and preserving the status quo even when improvements are obvious.

The worst outcome is not complexity itself.

It is complexity without context.

Internal teams are left:

- Responsible for maintaining models they didn’t design

- Accountable for numbers they didn’t define

- Asked to explain behavior they can’t justify

- Forced to reverse engineer intent from SQL

This leads to predictable behavior:

- Defensive changes

- Local fixes instead of systemic ones

- Gradual divergence from original design

- Quiet decay of trust and adoption

The warehouse still works.

The organization no longer feels fully in control of it.

Why Data Warehouse Consulting Must Design Its Own Exit

Exits fail when they are treated as documentation tasks rather than architectural outcomes. If a system cannot be reasoned about, modified, and defended by internal teams, the problem is not knowledge transfer, it is that the system was never designed for independence.

A successful consulting engagement plans its exit from day one.

Not as a handoff checklist, but as a design requirement.

That means:

- Decisions are documented with rationale, not just outcomes

- Ownership is explicit and accepted internally

- Governance processes are operational, not advisory

- Teams are trained on why, not just how

- The system can evolve without consultant involvement

If the warehouse cannot be confidently operated without the consultants, the engagement has underdelivered, no matter how clean the technology is.

The Core Failure Pattern

A simple test exposes weak exits: if consultants had to disappear tomorrow, could internal teams confidently explain, change, and defend the system’s behavior? If not, the engagement delivered assets, not capability.

Data warehouse consulting often assumes:

“If we build it well, the organization will figure out the rest.”

In practice, it rarely does.

Without a clear exit strategy:

- Confidence erodes

- Complexity feels unsafe

- Teams regress to old habits

- Leadership questions the investment

All while the technology continues to function perfectly.

Data warehouse consulting does not fail at delivery.

It fails at departure.

If an engagement does not leave behind clarity, confidence, and internal ownership, it has simply postponed failure until after the consultants are gone, even when the tech is exactly right.

The Organizational Cost of Getting This Wrong

When data warehouse consulting underdelivers, even with strong technology, the damage extends far beyond the warehouse itself.

The cost is not just financial.

It is organizational, cultural, and long lasting.

Wasted Spend

Financial loss is the easiest cost to see, and often the smallest. The deeper loss is optionality: the ability to justify future investments, experiment safely, and evolve data capabilities without re-litigating past failures.

Organizations invest in:

- Modern cloud platforms

- Consulting engagements

- Internal engineering time

- Migration programs that span months or years

When the outcome fails to change decision making:

- The spend becomes difficult to defend

- ROI narratives collapse

- Data investments are labeled “overhead”

What makes this especially painful is that the technology often works.

Leadership struggles to explain why so much was spent for so little visible impact.

Burned Trust

Trust loss changes how organizations behave. Teams hedge decisions, leaders demand excessive proof, and innovation slows, not because people lack ambition, but because the cost of being wrong feels too high. When consulting fails:

- Business teams become skeptical of future data initiatives

- Executives hesitate to sponsor analytics projects

- Engineers and analysts feel their work is undervalued

- Data becomes associated with disruption instead of clarity

Once trust is burned, it is difficult and slow to rebuild.

Future efforts are met with:

- More scrutiny

- Less patience

- Lower tolerance for change

- Stronger resistance from business users

Future Initiatives Get Blocked

Once an organization internalizes a failed transformation, risk tolerance resets. Even well scoped, well justified initiatives inherit the burden of proof, and many never make it past that gate. Perhaps the most damaging outcome is what follows.

After a failed consulting engagement:

- New data projects are delayed or denied

- Platform upgrades are postponed

- Governance conversations are avoided

- Strategic analytics initiatives lose executive backing

Not because they are bad ideas, but because the organization has been burned before.

The phrase “we already tried that” becomes a blocker for years afterwards.

“We Tried Consulting, It Didn’t Work”

This conclusion collapses distinct failures into a single narrative. It confuses execution gaps, ownership gaps, and adoption gaps with the viability of consulting itself, making it harder to diagnose what actually went wrong.

It is rarely accurate, but it becomes an accepted truth.

The organization concludes:

- Consulting doesn’t deliver value

- Data transformations are overhyped

- The problem must be unsolvable

What is lost in that conclusion is nuance.

The failure was not:

- Consulting as a discipline

- Modern data platforms

- Technical capability

It was the mismatch between organizational readiness and technical delivery.

The Compounding Effect

Organizational debt compounds faster than technical debt. Skepticism hardens, fatigue sets in, and even strong teams lower their ambitions to avoid repeating painful experiences.

These costs don’t stay isolated.

They compound over time:

- Each failed initiative increases resistance

- Each missed opportunity deepens skepticism

- Each avoided decision entrenches the status quo

Eventually, the organization stops trying to improve how data works, not because it doesn’t matter, but because failure feels inevitable.

Data warehouse consulting that underdelivers does more than waste money.

It poisons the ground for future progress.

That is why getting this right matters so deeply, not just for one project, but for the organization’s long term ability to use data as a strategic asset.

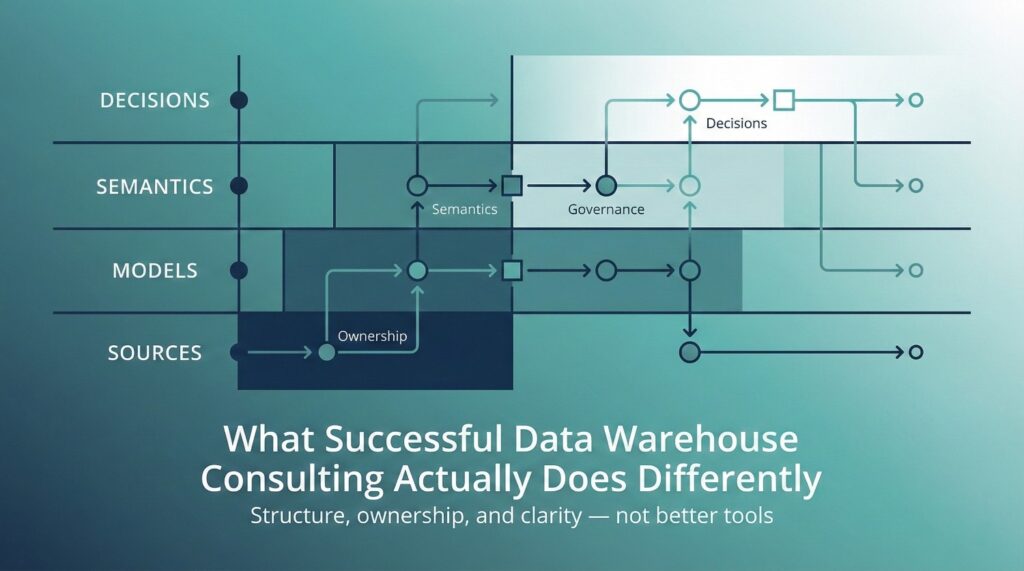

What Successful Data Warehouse Consulting Actually Does Differently

When data warehouse consulting does succeed, even in complex, high stakes environments, it is not because the consultants were smarter or the tools were inherently better.

It is because the engagement was structured differently at a fundamental level.

The successful cases tend to follow a consistent set of patterns that directly counter the failure modes described earlier.

Forces Ownership Early

Ownership delayed is ownership denied. Early ambiguity feels harmless when systems are still in motion, but it becomes paralyzing once decisions need to be defended. Successful engagements treat ownership as a prerequisite for progress, not a cleanup task.

Successful engagements do not postpone ownership discussions until after delivery.

They force clarity early in the engagement by answering:

- Who owns each core metric?

- Who approves semantic changes?

- Who is accountable when numbers are questioned?

This is uncomfortable work.

It often slows early progress.

But it prevents the far more expensive stall that happens later when no one has authority to decide.

Ownership is not documented as a suggestion, it is operationalized as an ongoing responsibility.

Makes Semantics Explicit

Successful data warehouse consulting treats meaning as first class work.

Instead of assuming shared understanding, it:

- Defines metrics precisely

- Documents inclusion and exclusion rules

- Makes assumptions visible

- Version controls meaning when it changes

Semantic clarity is not treated as cosmetic polish.

It is treated as infrastructure.

Because once semantics are explicit, trust becomes possible, and reuse becomes safe.

Aligns Incentives Across Teams

Most friction in data programs is not caused by lack of competence, but by misaligned incentives. Teams behave rationally according to how they are measured, even when that behavior undermines shared outcomes.

Many failed engagements ignore incentive misalignment.

Successful ones confront it directly.

They recognize that:

- Engineering is rewarded for delivery and stability

- Analytics is rewarded for responsiveness

- Finance is rewarded for consistency

- Leadership is rewarded for confidence and speed

When these incentives conflict, the warehouse becomes a battleground.

Effective consulting aligns incentives by:

- Designing shared definitions

- Reducing rework that punishes responsiveness

- Making ownership visible so responsibility is not diffused

When incentives align, cooperation replaces constant negotiation.

Creates Business Visible Milestones

Business visible milestones translate progress into confidence. They allow leaders to see risk being retired and ambiguity being removed, not just work being completed. Successful engagements make progress visible outside the data team.

Instead of milestones like:

- “Model X deployed”

- “Pipeline Y complete”

They use milestones like:

- “This executive question now has a trusted answer”

- “This report no longer requires reconciliation”

- “This metric is now owned and stable”

Business visible milestones:

- Build confidence

- Reduce skepticism

- Justify investment

- Anchor adoption

Without them, even real progress feels abstract and fragile.

Transfers Decision Making, Not Just Code

The true measure of a successful engagement is whether internal teams can make and defend decisions without external validation. Code can be copied; confidence and authority cannot.

One of the most important differences appears at the end of the engagement.

Successful consulting does not just transfer:

- SQL

- Pipelines

- Dashboards

- Infrastructure

It transfers:

- Decision authority

- Semantic ownership

- Governance responsibility

- Confidence to operate and evolve the system

Internal teams don’t just inherit a warehouse.

They inherit the ability to run it deliberately.

That is the real handoff.

The difference between failed and successful data warehouse consulting is not effort or expertise.

It is whether the engagement changes:

- Who decides

- What is explicit

- How progress is understood

- What the organization can confidently own after consultants leave

When those patterns are present, even complex systems tend to land successfully.

When they are absent, even perfect technology quietly fails.

Is Your Engagement Headed for Failure?

Most data warehouse consulting engagements don’t fail suddenly; they erode over time.

They drift, quietly, predictably, with plenty of warning signs that are easy to rationalize.

The problem is that those warnings often sound reasonable at the moment. These phrases persist because they reduce immediate discomfort. They delay decisions, avoid conflict, and keep delivery moving. In the short term, that feels responsible. In the long term, it compounds ambiguity.

If you hear the following phrases repeatedly, the engagement is likely optimizing for delivery while accumulating long term risk.

“We’ll Define It Later”

This usually means:

- No one wants to make a decision yet

- Ownership is unclear or politically sensitive

- Teams hope implementation will “clarify” meaning

What actually happens:

- Ambiguity gets encoded into models

- Temporary assumptions become permanent

- Every downstream consumer interprets differently

Deferring definitions does not meaningfully preserve flexibility.

It locks in confusion at scale.

If semantics are not defined early, they will be defined implicitly, and inconsistently, by whoever builds first. Defining semantics later is not a neutral delay, it is a structural choice that determines who gets to define meaning by default. In practice, meaning is set by whoever ships first, not by whoever owns the outcome.

“Just Match the Old Numbers”

This sounds pragmatic. In practice, it is often destructive.

What this really means:

- Legacy logic is being treated as truth

- Historical inconsistencies are being preserved without scrutiny

- The migration is avoiding uncomfortable conversations

What it leads to:

- Complex, brittle transformations

- Logic that no one understands or trusts

- A new system that inherits old failures

- No improvement in decision confidence

Matching legacy outputs prioritizes comfort over understanding. It prevents organizations from learning which numbers were wrong, fragile, or politically convenient, and why.

Matching old numbers without understanding why they look that way guarantees that nothing improves, only that the same problems are now more expensive to maintain.

“The Business Will Adopt Once It’s Live”

This is one of the most common and dangerous assumptions.

It assumes:

- Adoption is logical

- Trust is automatic

- Correctness is enough

In reality:

- Adoption is emotional

- Trust is earned through predictability and ownership

- New systems feel risky until proven safe

When this belief is present:

- Business users are excluded from validation

- Communication is minimal

Adoption outcomes are largely determined before going live. If trust, ownership, and communication are absent during validation, no amount of post launch training will reverse the hesitation.

By the time adoption fails, it is blamed on “change resistance”, not on missing trust building work.

“Governance Can Wait”

This phrase frequently precedes governance failure.

It suggests:

- Speed is being prioritized over stability

- Ownership conversations are uncomfortable

- Teams believe rules slow progress

What actually happens:

- Metric sprawl accelerates

- Schema drift goes unnoticed

- Conflicting logic multiplies

- Trust erodes silently

Governance delayed is governance denied. Governance delay compounds cost in two dimensions: technical rework and organizational resistance. By the time alignment feels urgent, both systems and opinions have already hardened.

By the time it feels necessary, the system has already hardened around bad assumptions, and fixing them becomes politically and technically expensive.

How to Use This Diagnostic Honestly

Hearing one of these phrases once is not a failure.

Hearing several of them repeatedly is a strong signal that:

- Decisions are being avoided

- Responsibility is diffused

- The engagement is optimizing for short term delivery

- Long term absorption is being ignored

At that point, the question is not:

“Are we making progress?”

It is:

“Are we building something the organization can actually own?”

If these warning signs persist, the technology may still succeed, but the consulting engagement will likely underdeliver.

How to Fix a Technically Successful but Organizationally Failing Warehouse

When a warehouse is technically sound but failing to change behavior, the instinct is often to add more features.

That instinct is understandable–but wrong.

Adding features feels productive because it produces visible output. But when trust is low, new surface area amplifies confusion faster than it creates value. Organizations interpret motion as avoidance when fundamentals remain unresolved.

At this stage, the primary problem is not capability.

It is absorption.

Fixing this often requires slowing down, re centering, and deliberately rebuilding the conditions that allow the organization to trust and use what already exists.

Reset Success Metrics

The first fix is conceptual rather than technical.

Stop measuring success by:

- Models shipped

- Dashboards delivered

- Queries optimized

- Pipelines completed

And start measuring:

- Which decisions now rely on the warehouse

- Where reconciliation work has disappeared

- Whether executives use numbers without caveats

- How often definitions are questioned

The most reliable adoption signals are negative indicators, work that no longer needs to happen. Fewer reconciliations, fewer clarification meetings, and fewer parallel reports signal success more clearly than any delivery metric. Until success is redefined in organizational terms, teams will continue optimizing for delivery instead of impact.

Pause Feature Work

An intentional pause is not a lack of ambition; it is an assertion of leadership. It signals that clarity and trust are prerequisites for scale, not obstacles to it. This is uncomfortable, but often necessary.

When trust is low, adding more features:

- Increases surface area for confusion

- Introduces new definitions before old ones are stable

- Signals that speed matters more than clarity

A short, intentional pause allows teams to:

- Stabilize semantics

- Reduce noise

- Address foundational issues

- Communicate clearly without competing priorities

This is not stagnation.

It is a deliberate recovery.

Establish Ownership (Explicitly and Publicly)

Ownership only works when it is visible at the point of use. If users do not know who stands behind a number, ownership exists only on paper, and paper authority does not build trust. Nothing changes until ownership is explicitly named.

That means:

- Assigning owners to core metrics

- Making those owners visible to the business

- Giving them authority to approve changes

- Holding them accountable when numbers are questioned

Ownership must be operational, not ceremonial.

If engineers are still being asked to arbitrate meaning, ownership has not actually been established.

Publish Definitions (And Stand Behind Them)

Definitions that live only in documents no one reads don’t count.

Effective definition publishing means:

- Clear metric descriptions

- Inclusion and exclusion rules

- Known limitations

- Effective dates for changes

- Owners listed by name

More importantly, it means leadership is willing to say:

“This is the definition we are using, even if it’s imperfect.”

Stability builds trust faster than theoretical correctness. In practice, users forgive imperfect definitions faster than shifting ones. Predictability allows teams to plan, commit, and act, even while improvements continue behind the scenes.

Rebuild Trust Deliberately

Trust does not reliably return on its own.

It must be rebuilt through:

- Transparent communication about changes

- Pre announcing differences before users discover them

- Explaining why numbers shifted, not just that they did

- Inviting business teams into validation, not just sign-off

This phase is relational, not technical.

It requires:

- Patience

- Repetition

- Consistency

- Visible leadership support

When users feel safe using the warehouse, even when it isn’t perfect, adoption follows.

The Hard Truth

You do not fix an organizational failure with better SQL alone.

You fix it by:

- Redefining success

- Slowing down intentionally

- Making ownership unavoidable

- Choosing clarity over speed

- Treating trust as a deliverable

A technically successful warehouse is not a lost cause.

But without deliberate organizational repair, it will remain a reference system, never a decision system.

Final Thoughts

By the time a data warehouse is technically sound, the primary limiting factor is no longer technology.

The platform works.

The pipelines run.

The models are correct.

What determines success from that point forward is how the organization is designed to use them.

Technology Enables Outcomes

Over the last decade, data platforms have largely commoditized core capabilities. Performance, scalability, and reliability are no longer differentiators, they are baseline expectations. As a result, competitive advantage has shifted away from tooling and toward how organizations operationalize shared data.

Modern data platforms are extraordinarily capable.

They enable:

- Scale

- Speed

- Reliability

- Flexibility

But they are fundamentally neutral with respect to organizational outcomes.

They do not decide:

- What metrics mean

- Who owns the number

- How disagreements are resolved

- When change is acceptable

- What “good enough” looks like

Those decisions live outside the code.

Organizations Determine Outcomes

Two organizations can deploy the same warehouse with the same tools and arrive at materially different results.

The difference is rarely talent or effort.

It is organizational design.

Specifically:

- Who has authority to decide

- Whether semantics are stable or fluid

- How governance is embedded

- How progress is communicated

- Whether trust is actively cultivated or passively hoped for

Data warehouse consulting succeeds when it reshapes these elements, not just the technical stack.

When Data Warehouse Consulting Actually Works

Data warehouse consulting delivers value when it changes how the organization operates around data. The highest leverage consulting engagements do not just deliver systems, they change behavior. They leave behind clearer decisions, fewer disputes, and a shared understanding of what the numbers mean and who stands behind them.

It succeeds when it:

- Changes how decisions are made

Decisions become faster, more confident, and less dependent on reconciliation. - Clarifies ownership

Everyone knows who owns which numbers, and where to escalate questions. - Builds durable trust

Data behaves predictably, changes are explained, and people feel safe using it in high stakes contexts.

When these conditions exist, technology compounds value instead of exposing fragility.

Final Takeaway

If:

- The technology is right

- The warehouse is stable

- The tools are modern

And the system still fails to change behavior,

Then the problem is no longer primarily technical.

Data warehouse consulting is not a software exercise.

It is organizational design applied to data.

Until leadership treats it that way, even the best built warehouses will continue to work correctly, and quietly fail to matter.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Because technology alone doesn’t change how an organization makes decisions. When ownership is unclear, semantics are unstable, governance is avoided, and trust isn’t actively built, even perfectly functioning systems fail to be adopted.

No. That is technical completion, not organizational impact. Success is measured by whether people trust the numbers, use them confidently in decisions, and stop maintaining parallel systems.

Lack of ownership. When no one is accountable for defining, defending, and evolving metrics, disputes escalate, changes stall, and trust erodes, even if nothing is technically broken.

Because spreadsheets feel safer. They offer control, familiarity, and flexibility when warehouse numbers change without explanation or ownership. This behavior is rational, it signals trust has not been earned.

They can help design the conditions for trust, but they cannot own it. Adoption requires visible leadership backing, explicit ownership, clear communication, and psychological safety for business users.

Governance is often equated with bureaucracy. When avoided, metric sprawl, schema drift, and conflicting logic emerge. Lightweight, embedded governance is what enables agility to scale without chaos.

Consultants can recommend and model options, but they lack the authority, accountability, and political cover to decide metric definitions, historical corrections, or tradeoffs. When forced into that role, trust collapses.

If you hear:

- “Which number is right?”

- “This used to match”

- “Let’s double check in Excel”

- “We’ll define it later”

The issue is organizational. Technology is only revealing it.

Pause feature work, reset success metrics around trust and adoption, establish explicit ownership, publish definitions, and rebuild confidence deliberately. More features will not fix a trust gap.

Without intentional knowledge transfer, internal teams inherit complexity without context. Fear replaces confidence, and the system slowly decays after consultants leave, even if nothing breaks immediately.

If the technology is right and the warehouse still fails, the problem is no longer technical.

Data warehouse consulting succeeds only when it is treated as organizational design, not a delivery project.