Table of Contents

Introduction

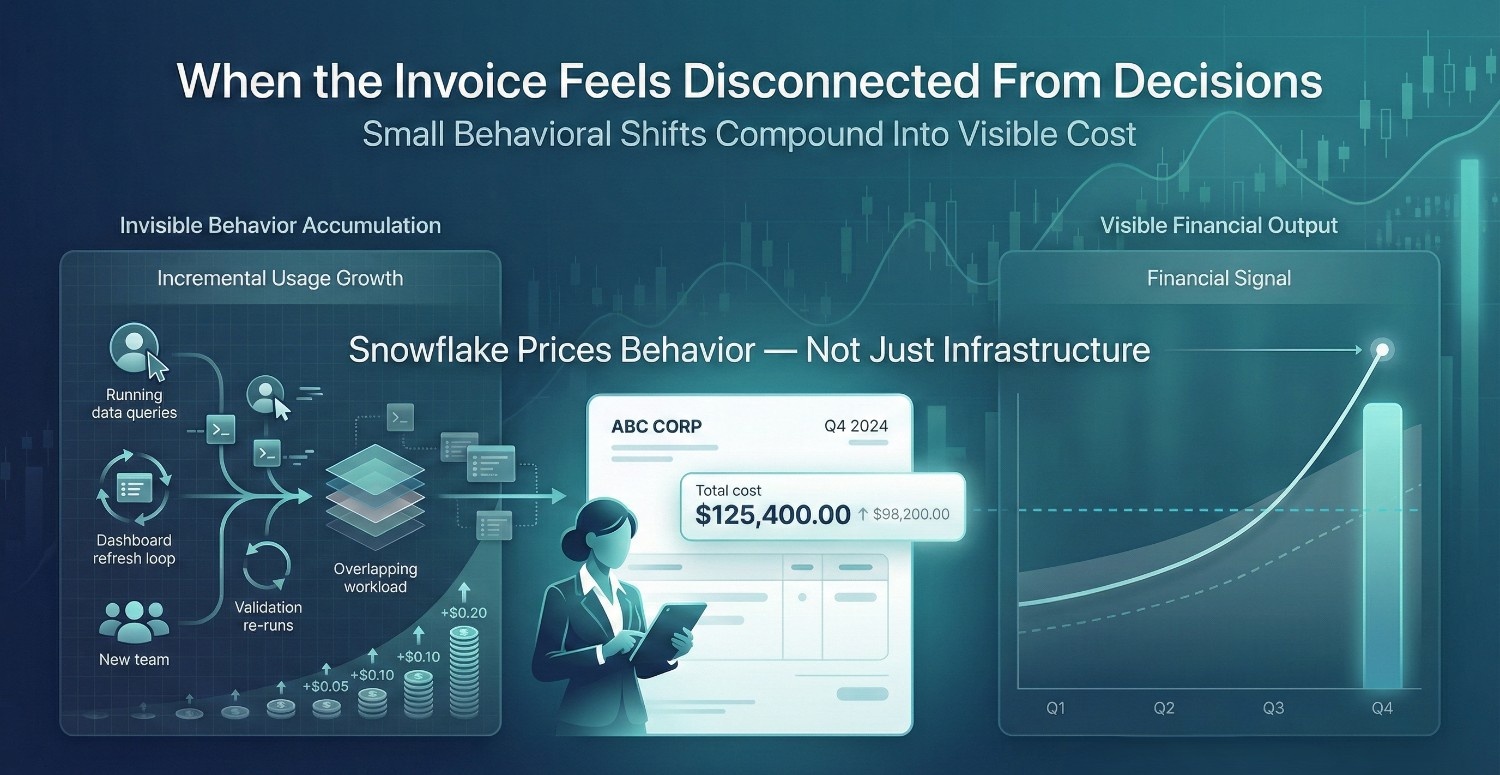

For many finance teams, the moment can feel uncomfortably familiar. The Snowflake invoice arrives.

The number is higher than forecast. No system was down. No one reports a mistake. Nothing obviously went wrong. And yet, the bill is meaningfully larger than expected.

This is often the point where Snowflake cost shifts from a data concern to finance concern. What makes this moment frustrating is not just the amount, it’s the lack of a clear explanation. Unlike traditional IT spend, there’s no new server purchase to point to, no license expansion, no obvious capacity upgrade.

The cost increase feels detached from any deliberate decision.That’s actually not because something broke. It’s because Snowflake operates on a different economic model than most finance teams are used to managing.

Why Snowflake Cost Surprises Even Well-Run Organizations

Snowflake can surprise finance teams precisely because it works as intended.

Snowflake removes friction:

- Teams get faster access to data

- More users can run analytics independently

- Experiments are cheap to start

- Scaling does not require procurement approval

Those are strengths, but they also allow usage to expand quietly if governance does not keep pace. Cost increases don’t arrive through:

- A budget request

- A purchase order

- A planned capacity change

They arrive through dozens, or hundreds, of small, reasonable actions taken across the organization. From finance’s perspective, this can feel like a failure of control. From Snowflake’s operating model perspective, it reflects adoption growth.

The Core Misunderstanding

Unlike capital intensive infrastructure models, usage based pricing exposes behavioral change immediately, which shortens feedback cycles but increases perceived volatility.

Here’s the key idea most organizations miss early:

Snowflake bills typically don’t spike because teams are careless. They increase because Snowflake prices behavior, rather than fixed assets.

Traditional systems price things finance can see and approve:

- Servers

- Licenses

- Contracts

Snowflake prices dimensions of usage that finance rarely tracks directly:

- How often questions are asked

- How many people ask them at once

- How often answers are re-checked

- How much parallel work exists due to low trust

When behavior changes, even slightly, cost follows.

Why the Surprise Feels Sudden

Snowflake cost rarely grows in a smooth, linear way.

Instead:

- A new team is onboarded

- Self-service expands

- Validation work increases

- Migration or backfill activity spikes

Each change feels incremental. Together, they cross a threshold that shows up clearly on the invoice. Because Snowflake doesn’t enforce hard limits by default, the primary early signal is financial rather than operational. That’s why finance teams experience Snowflake cost as a surprise rather than a gradual drift.

What This Article Will Clarify

This article is not about blaming engineering or analytics teams. It will explain:

- Where Snowflake cost surprises actually come from

- Why invoices feel disconnected from planning

- How organizations can prevent surprises without slowing analytics or innovation

The goal is not to make Snowflake cheaper at all costs. The goal is to make Snowflake cost:

- Explainable

- Predictable

- Governable

Once finance understands that Snowflake is pricing how the business uses data rather than only infrastructure, the conversation shifts from shock to strategy. Organizations that separate migration, validation, and steady state usage in reporting frameworks tend to reduce perceived unpredictability significantly.

Snowflake Pricing Breaks Traditional Finance Mental Models

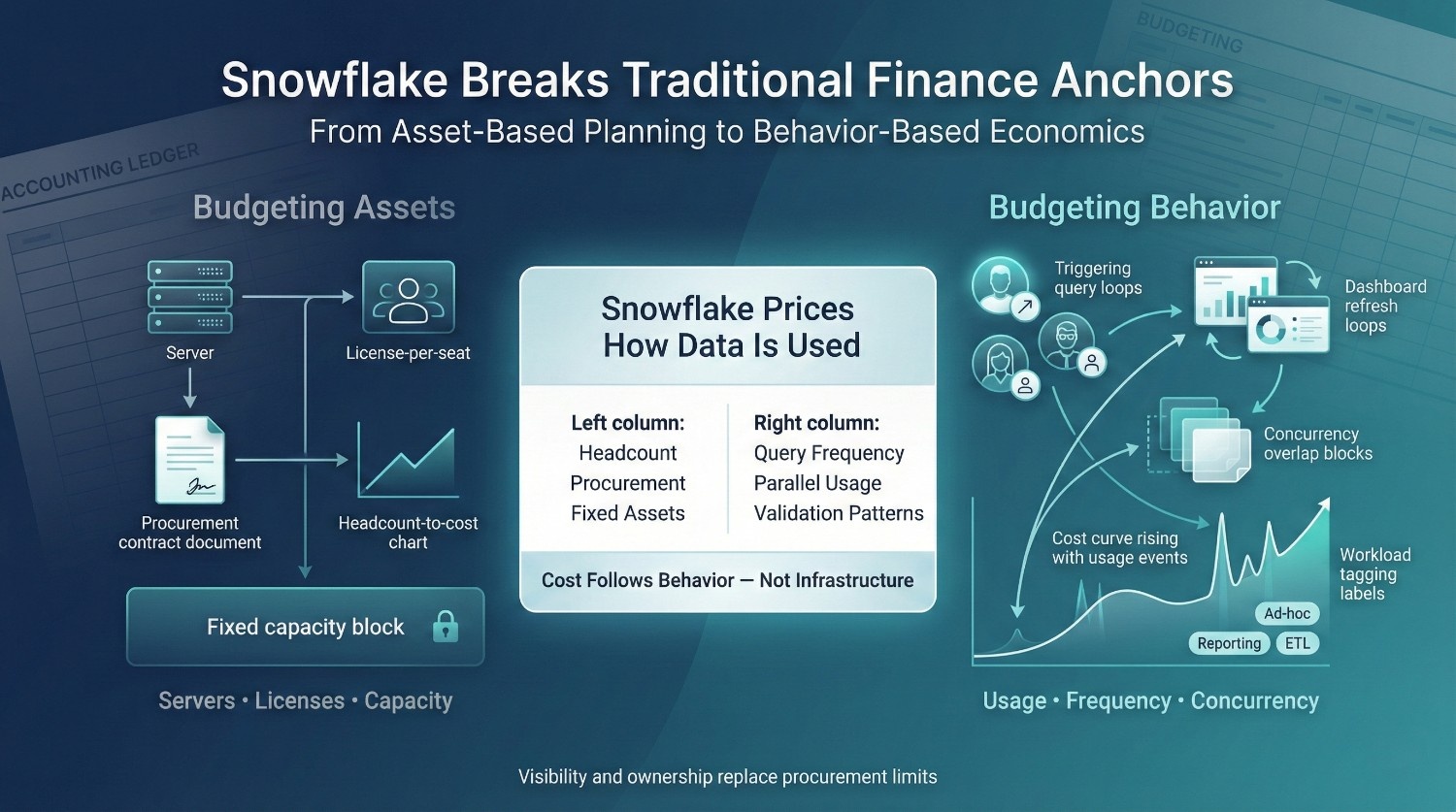

Snowflake pricing can feel uncomfortable to finance teams because it doesn’t align with how most traditional financial controls are designed. There are:

- No fixed licenses

- No per-seat pricing

- No mandatory pre-purchased capacity by default

That reduces the familiar anchors finance relies on to forecast, approve, and attribute spend.

In traditional systems, cost is tied to assets:

- Servers are bought or leased

- Licenses are counted per user

- Capacity is approved in advance

Those assets map cleanly to:

- Headcount plans

- Project budgets

- Departmental ownership

Snowflake significantly alters that model entirely.

Why Snowflake Cost Doesn’t Map Cleanly

FinOps maturity models consistently show that cost transparency improves only after ownership is assigned at the workload or team level rather than at the infrastructure level. Snowflake cost does not directly scale with:

- The number of employees

- The number of projects

- The number of departments

It scales with how often data is used, by whom, and in what patterns. Two teams with the same headcount can generate materially different Snowflake bills because:

- One reuses shared models

- The other duplicates logic

- One trusts shared metrics

- The other re-runs validations constantly

From a finance perspective, this can be disorienting. There’s no obvious “owner” to charge. No clean allocation rule. No simple multiplier to apply during planning. The spend can feel detached from organizational structure, even though it’s deeply tied to organizational behavior.

From Budgeting Assets to Budgeting Behavior

This is the mental shift Snowflake forces. Snowflake does not ask finance to budget:

- Hardware

- Licenses

- Capacity

It asks finance to budget for:

- Query frequency

- Concurrency

- Self-service adoption

- Validation and rework

Those are not line items finance traditionally governs directly. That’s why Snowflake cost can often feel:

- Hard to explain

- Hard to forecast

- Hard to attribute

Not because it’s uncontrollable, but because it requires a different control model. Organizations that implement workload level tagging and chargeback models tend to reduce forecast variance significantly within two to three planning cycles.

Why This Gap Creates Surprise

When finance applies asset-based thinking to behavior-based pricing:

- Forecasts underestimate growth

- Variance explanations sound vague

- Cost spikes feel unjustified

Snowflake didn’t break budgeting discipline. It exposed a mismatch between traditional financial planning methods and actual data usage patterns.

Once finance recognizes that Snowflake is pricing behavior, not infrastructure, the path forward becomes clearer: cost control comes from visibility, ownership, and usage discipline, not from traditional procurement-style limits. That realization is the first step toward reducing cost surprises.

The Biggest Misconception

“We only pay for what we use” is Snowflake’s most quoted promise, and the one most likely to mislead finance teams. Technically, it’s accurate within the billing model. Financially, it can be incomplete without governance framing.

The phrase implies intention and control: that “use” is deliberate, bounded, and predictable. In practice, Snowflake prices compute whenever it is active, regardless of whether that activity was planned or explicitly reviewed.

What “Use” Actually Means in Snowflake

In Snowflake, “use” is defined by runtime activity rather than by a formal business approval event.. It’s a runtime condition. You pay when:

- Warehouses are running , even if they’re lightly loaded

- Queries are executing, including background refreshes and validations

- Compute stays active due to concurrency, a steady trickle of queries can prevent auto-suspend

- The same logic is re-run, dashboards, reconciliations, and investigations repeat work

From a finance perspective, this activity may not appear as a discrete budgeting decision. From Snowflake’s perspective, it’s all billable activity.

Why “Idle” Compute Still Burns Credits

A common surprise is paying for compute that appears underutilized. This happens when:

- Warehouses are sized larger than needed

- Auto-suspend is set too conservatively

- Multiple small queries keep the warehouse alive

- Shared warehouses never fully go quiet

Auto suspend configuration and warehouse sizing policies are among the most common root causes identified in Snowflake cost optimization reviews. The warehouse isn’t “doing nothing”. It’s available, and availability has a cost.

How Small Inefficiencies Compound

Individually, these behaviors are harmless:

- One extra dashboard refresh

- One more validation query

- One analyst running the same check twice

At scale, they compound:

- Dozens of dashboards

- Hundreds of users

- Thousands of repeated queries

Snowflake doesn’t amortize inefficiency across time. It reflects it immediately in spend.

The Financial Reality

“We only pay for what we use” is accurate, but incomplete without governance. A better framing for finance is:

We pay for everything the organization permits to occur within the platform.

Organizations that implement workload level ownership and cost dashboards typically see invoice volatility decline within a few reporting cycles. Once finance understands that Snowflake is monetizing behavior, not intent, the surprise disappears. Cost control stops being about catching mistakes and starts being about shaping usage.

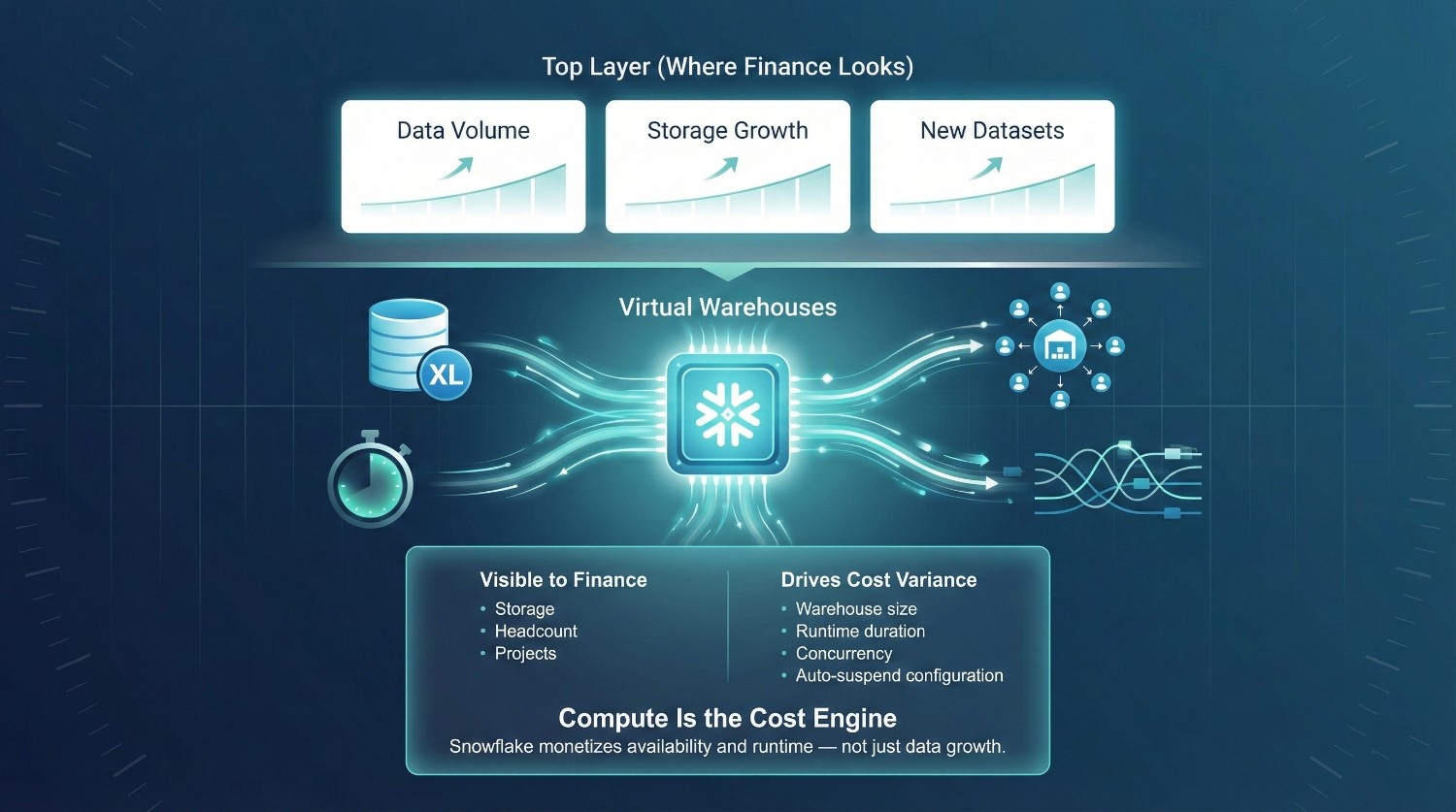

Compute Is the Real Snowflake Cost Shock

When finance teams investigate an unexpected Snowflake bill, they often start in the wrong place.

They look at:

- Data volume

- Storage growth

- New datasets

In many cases, those are secondary factors rather than primary drivers. The real driver of Snowflake cost surprises is compute, specifically, how virtual warehouses are sized, shared, and allowed to run.

Virtual Warehouses Are the Cost Engine

In Snowflake, most variable spend is driven by virtual warehouses.Warehouses consume credits when they are:

- Running

- Actively executing queries

- Kept alive by continuous activity

Storage grows slowly and predictably. Cloud services are typically secondary in comparison to warehouse compute. Compute is where cost variance lives. Snowflake customer cost reviews consistently identify warehouse sizing and auto suspend configuration as the highest leverage optimization areas. And compute is governed, often implicitly, by dozens of small configuration choices that finance rarely sees.

Oversized Warehouses Inflate Spend Quietly

Oversizing is common, particularly during early adoption phases. Teams choose larger warehouses because:

- Performance complaints are politically risky

- The cost difference between sizes feels abstract

- No one is measured on efficiency

The result:

- Light workloads run on heavy compute

- Queries may finish faster than required for the workload

- Credits are consumed at a higher rate per second

From a finance perspective, no explicit purchasing decision changed.

From Snowflake’s view, every second costs more.

Long Auto-Suspend Times Create Invisible Waste

Auto-suspend is Snowflake’s primary cost control, but it’s often misconfigured. Common patterns include:

- Suspend times set too high “just in case”

- Warehouses kept warm for convenience

- Shared warehouses never fully going idle

Even a few extra minutes of runtime per hour can compound significantly across days and teams.

This waste is:

- Small in any single instance

- Large in aggregate

Often difficult to detect without deliberate monitoring

Shared Workloads Quietly Multiply Cost

Shared warehouses feel efficient. In practice, they are one of the fastest ways to lose cost control. Workload isolation is widely cited as one of the most effective mechanisms for improving both cost attribution and performance predictability. When multiple workloads share compute:

- Concurrency keeps warehouses running

- Auto-suspend rarely triggers

- One team’s activity extends another’s cost

Finance sees a single warehouse line item. In reality, it’s subsidizing unrelated work across the organization.

Why Finance Only Sees This at Month-End

Snowflake does not interrupt usage when costs rise. It reports them after the fact.

Without:

- Real-time visibility

- Clear workload ownership

- Spend attribution

Cost growth feels sudden, even though it accumulated gradually. The shock is rarely caused by one mistake. It’s caused by compute continuing to operate according to its configured parameters.

Real time spend dashboards and workload level tagging significantly reduce month end invoice surprises in large Snowflake deployments. Once finance understands that Snowflake compute monetizes availability and behavior, not just work performed, the pattern becomes clear. And with that clarity, the surprise stops being mysterious, and becomes governable.

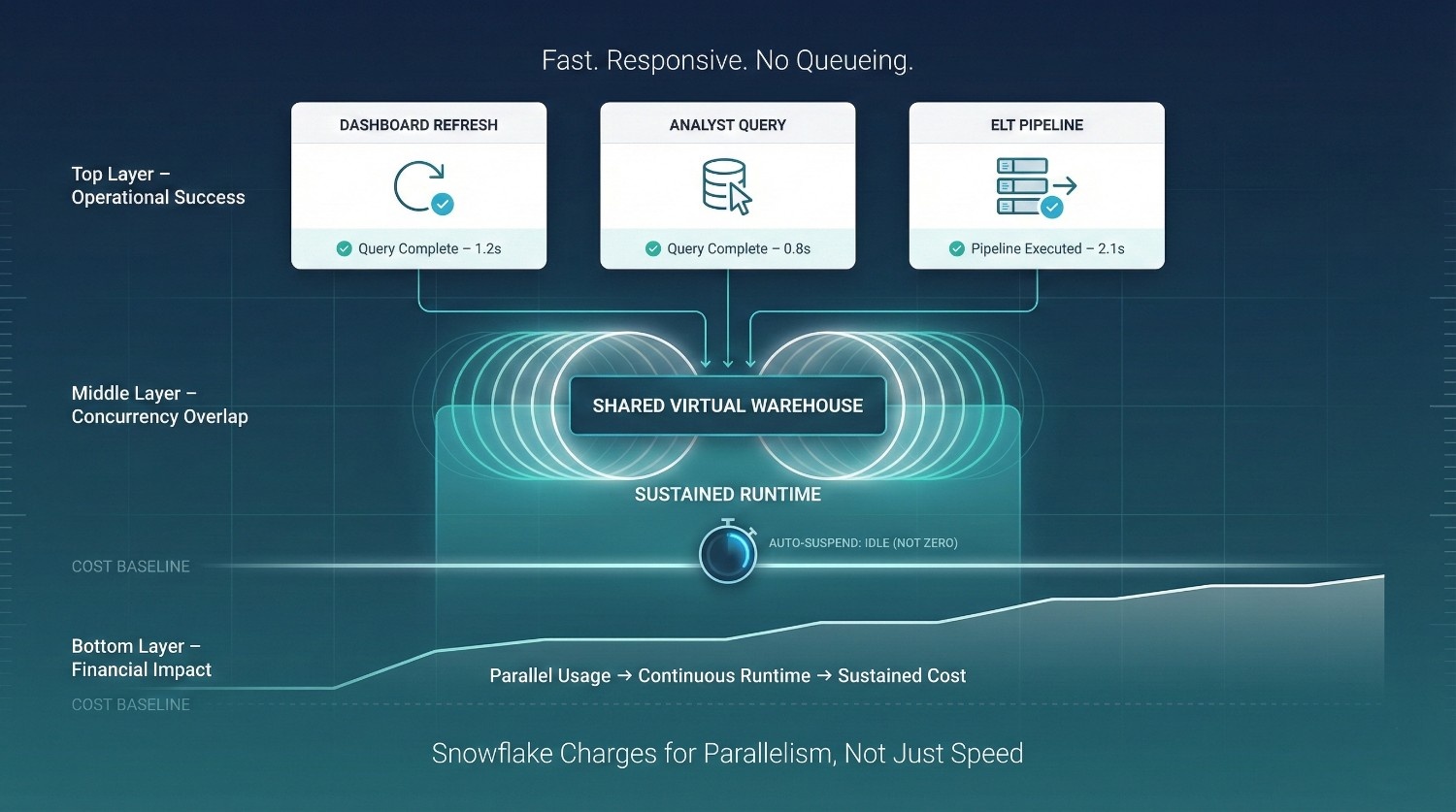

Concurrency

Concurrency is one of the least intuitive, and potentially expensive, drivers of Snowflake cost. From an operational standpoint, concurrency feels like a success. Queries don’t queue. Dashboards stay fast. Teams don’t wait on each other. Everything “just works.” Financially, that same success can quietly multiply spend.

One Query vs. 50 Users

A single query running occasionally is easy to reason about. Fifty users running queries at the same time is not fifty times the cost, but it’s close enough to surprise finance teams when it happens consistently.

Concurrency extends warehouse runtime:

- More queries overlap

- Warehouses stay active longer

- Auto-suspend triggers less often

Even if individual queries are efficient, simultaneous usage prevents compute from ever turning off.

When Workloads Collide

Snowflake makes it easy for very different workloads to run together:

- Dashboard refreshes

- Ad-hoc analyst queries

- ELT and transformation jobs

Each workload is reasonable on its own. Together, they create a steady stream of activity that keeps warehouses alive. The result:

- Warehouses run nearly continuously

- Credits accrue around the clock

- No single team sees themselves as the cause

Concurrency often doesn’t appear as a sharp spike. It often appears as a sustained elevated baseline.

Why Concurrency Feels “Free” Operationally

In many legacy systems, concurrency created friction:

- Queries queued

- Performance degraded

- Users complained

Snowflake reduces that friction by allowing compute to scale elastically. From a user’s perspective:

- Queries still return quickly

- No one waits

- There’s no immediate visible cost signal

From finance’s perspective:

- Spend increases without any visible event

- There’s no purchase to approve

- No limit was technically exceeded

That’s why concurrency-driven cost feels invisible until the invoice arrives.

How Snowflake Cost Scales with Simultaneous Usage

Snowflake cost scales with:

- How many queries overlap

- How long warehouses remain active

- Whether scaling or multiple warehouses are involved

Concurrency doesn’t require inefficient queries. It requires many reasonable users acting at the same time. Large scale Snowflake cost reviews consistently identify concurrency overlap and shared warehouse design as primary contributors to sustained elevated compute baselines.

The Finance-Level Insight

Concurrency is not misuse. It’s adoption. But without isolation, guardrails, and visibility, concurrency turns success into surprise. Snowflake doesn’t charge for speed, it charges for parallelism. Understanding that distinction is critical for finance teams trying to explain why “nothing changed,” yet the bill did.

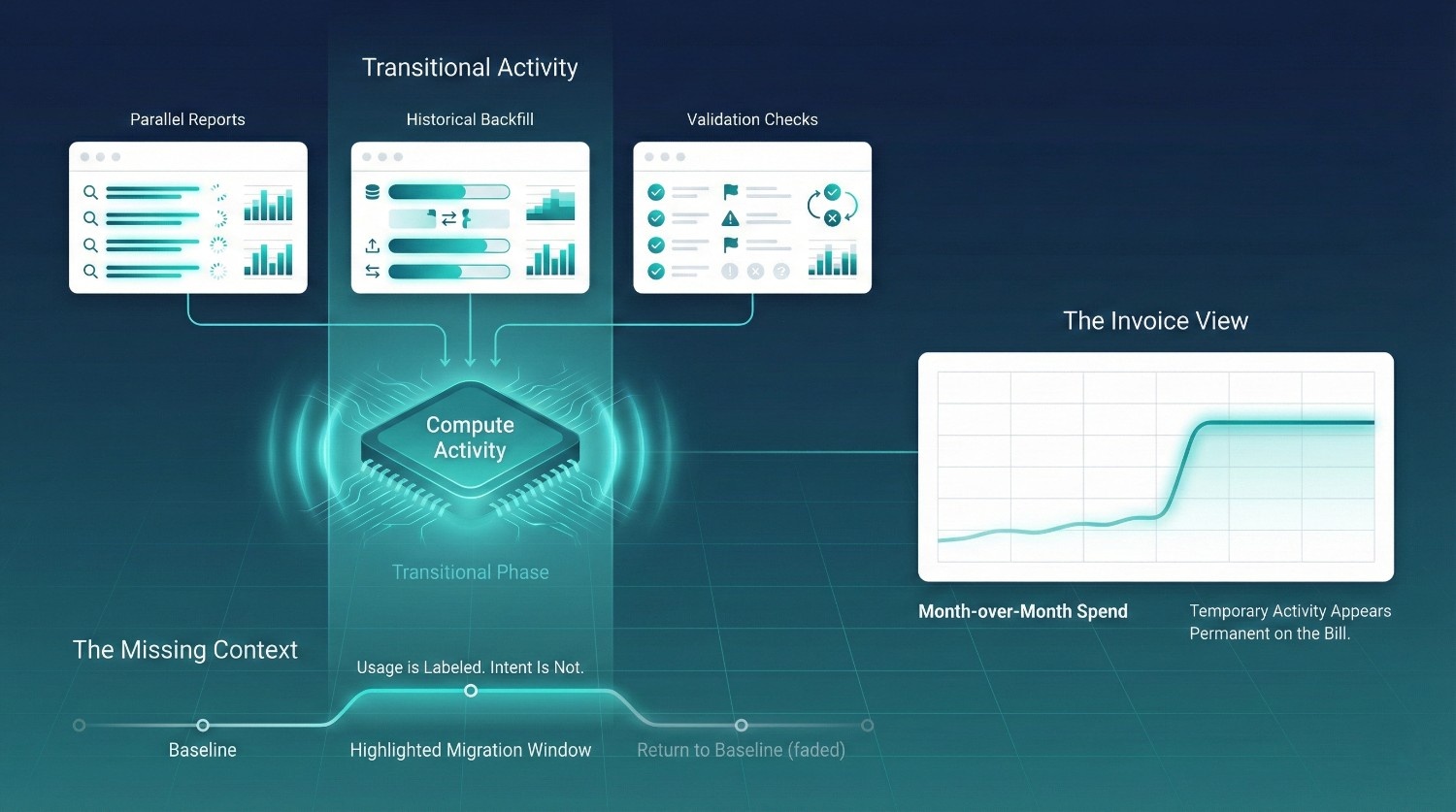

Temporary Workloads That Look Permanent on the Bill

One of the most common reasons Snowflake bills alarm finance teams is misclassification. Temporary workloads show up on the invoice the same way permanent ones do. Snowflake does not label intent, only usage. Without context, finance is left to assume the worst.

Migration Dual-Runs

During migrations, dual-running is almost unavoidable. Teams:

- Run reports in legacy systems and Snowflake in parallel

- Compare outputs repeatedly

- Keep both pipelines active “just in case”

This can significantly increase compute activity for a defined period of time. From a finance perspective, it looks like:

- A sudden, sustained increase in usage

- No clear signal that it will taper off

In reality, dual-runs are transitional. But unless they are time-boxed and communicated, they read as a new baseline. Enterprise migration programs frequently separate dual run spend in financial reporting to prevent transitional activity from distorting steady state forecasts.

Backfills and Reprocessing

Backfills are another major source of temporary spend. They occur when:

- Logic changes

- Historical data needs to be recomputed

- Bugs are corrected retroactively

Backfills:

- Run on large warehouses

- Scan large data volumes

- Often happen in bursts

They are expensive, but finite. On the invoice, however, a heavy backfill month looks identical to steady growth. Without narrative, finance has no way to distinguish cleanup from expansion.

Validation and Reconciliation Queries

Trust-building is computationally expensive. During periods of change:

- Teams re-run the same queries to confirm results

- Slight discrepancies trigger deeper investigation

- Multiple stakeholders validate independently

This behavior fades once confidence stabilizes, but during the transition, it creates dense compute usage. Again, Snowflake does exactly what it’s designed to do: it prices the activity. It does not signal when that activity is temporary.

Why Finance Mistakes Spikes for Structural Growth

Finance teams operate on patterns:

- Month-over-month trends

- Run-rate assumptions

- Forecast extrapolation

When temporary workloads aren’t labeled as such:

- Spikes are treated as permanent

- Forecasts are revised upward unnecessarily

- Cost anxiety escalates

The problem isn’t Snowflake cost itself. It’s missing context.

The Critical Insight

Temporary Snowflake workloads are normal, especially during migration and stabilization. What causes surprise is not the spend itself, but the absence of:

- Time boundaries

- Ownership

- Explicit communication

When temporary work is named, scoped, and time-boxed, Snowflake bills stop looking mysterious, and start looking intentional.

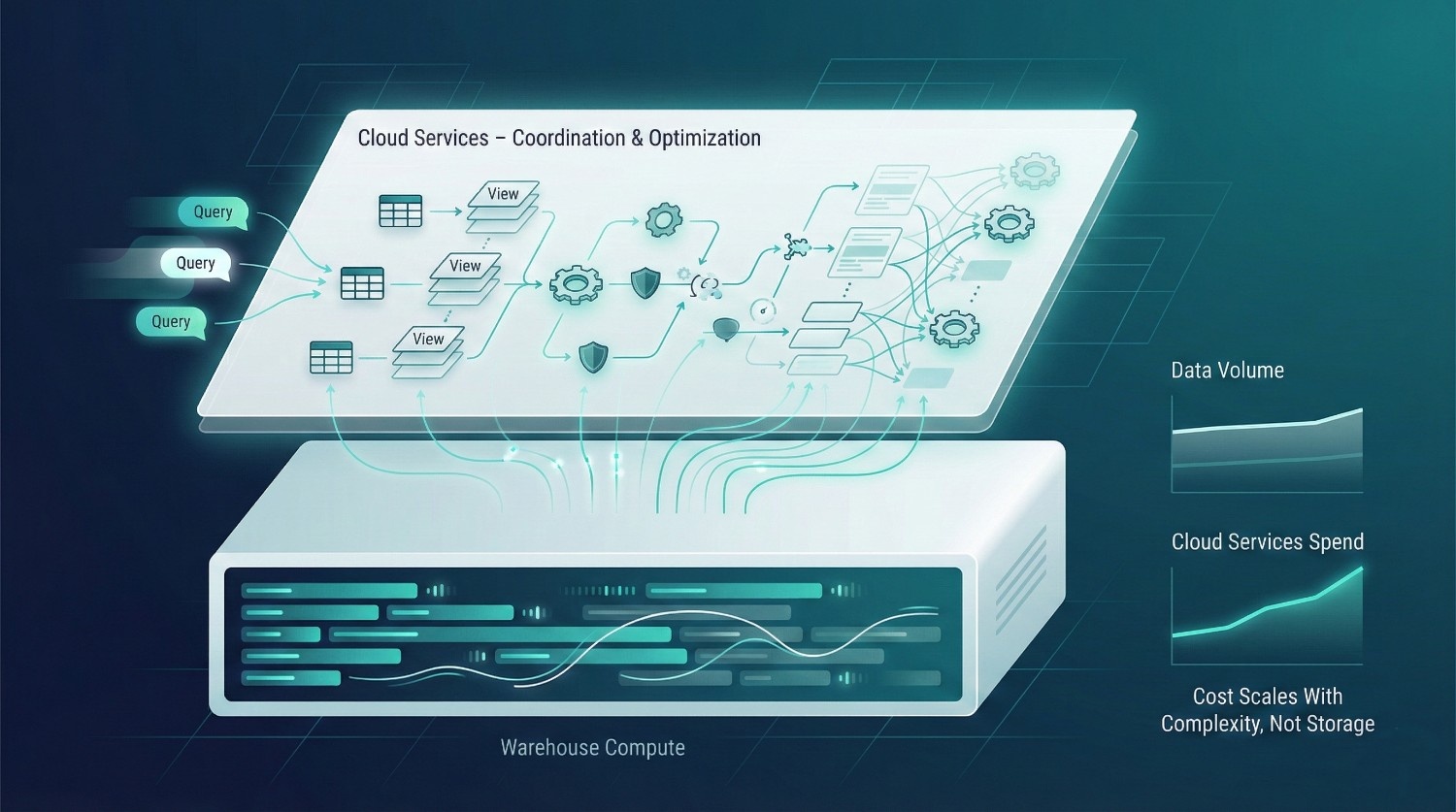

Cloud Services Cost

When finance teams review Snowflake bills, attention almost always goes to compute. That’s understandable, it’s the largest line item. There’s another category that can quietly grow in the background and is often under forecasted: Cloud Services cost.

What Cloud Services Cost Actually Covers

Cloud Services charges are not about data processing. They cover the “control plane” work Snowflake does behind the scenes, including:

- Metadata operations (parsing, planning, and managing query structure)

- Query compilation and optimization

- Transaction management

- Result caching coordination

- Security and access control checks

This activity does not directly scan user data. None of it runs warehouses directly. But all of it consumes resources, and is billable once usage crosses free thresholds.

Why This Cost Grows With Complexity, Not Volume

This is where finance teams often misinterpret the signal. Cloud Services cost does not primarily scale with:

- Data size

- Storage growth

- Single-query runtime

It scales with:

- The number of queries

- The complexity of SQL logic

- The number of objects involved (tables, views, joins)

- The number of users interacting concurrently

Examples that drive Cloud Services cost:

- Highly nested views and abstractions

- Complex dbt model graphs

- Many small queries rather than fewer consolidated ones

- Large numbers of dashboards refreshing independently

It is possible to have modest data volume and still see Cloud Services cost rise meaningfully as analytical complexity increases.

Why It’s Rarely Forecasted

Most Snowflake cost forecasts tend to focus on:

- Warehouse size

- Query runtime

- Storage growth

Cloud Services is often ignored because:

- It’s less visible in planning tools

- It feels “small” early on

- It’s harder to tie to a specific team or workload

By the time it becomes noticeable, it’s already embedded in daily usage patterns. Finance sees a line item growing without an obvious lever to pull.

Why It’s Often Misunderstood

Cloud Services cost is frequently misdiagnosed as:

- A Snowflake pricing quirk

- An inefficiency in query execution

- “Overhead” that should be zero

In reality, it’s a signal of analytical maturity and complexity. As organizations:

- Add more semantic layers

- Support more users

- Build richer analytical workflows

Cloud Services cost typically grows as analytical activity and complexity increase. The issue is not that it exists as a billing category. The issue is that no one is watching it, or explaining it.

The Finance-Level Insight

Cloud Services cost can be viewed as a coordination overhead within the platform. It reflects:

- How complex the data environment has become

- How many questions are being asked

- How much abstraction sits between raw data and answers

It’s rarely the biggest Snowflake cost driver, but it’s often the most confusing. When finance teams understand that Cloud Services cost grows with how sophisticated and active analytics become, not with data volume, it stops looking like noise, and starts looking like a diagnostic signal. Ignoring it doesn’t reduce it. Understanding it makes it predictable.

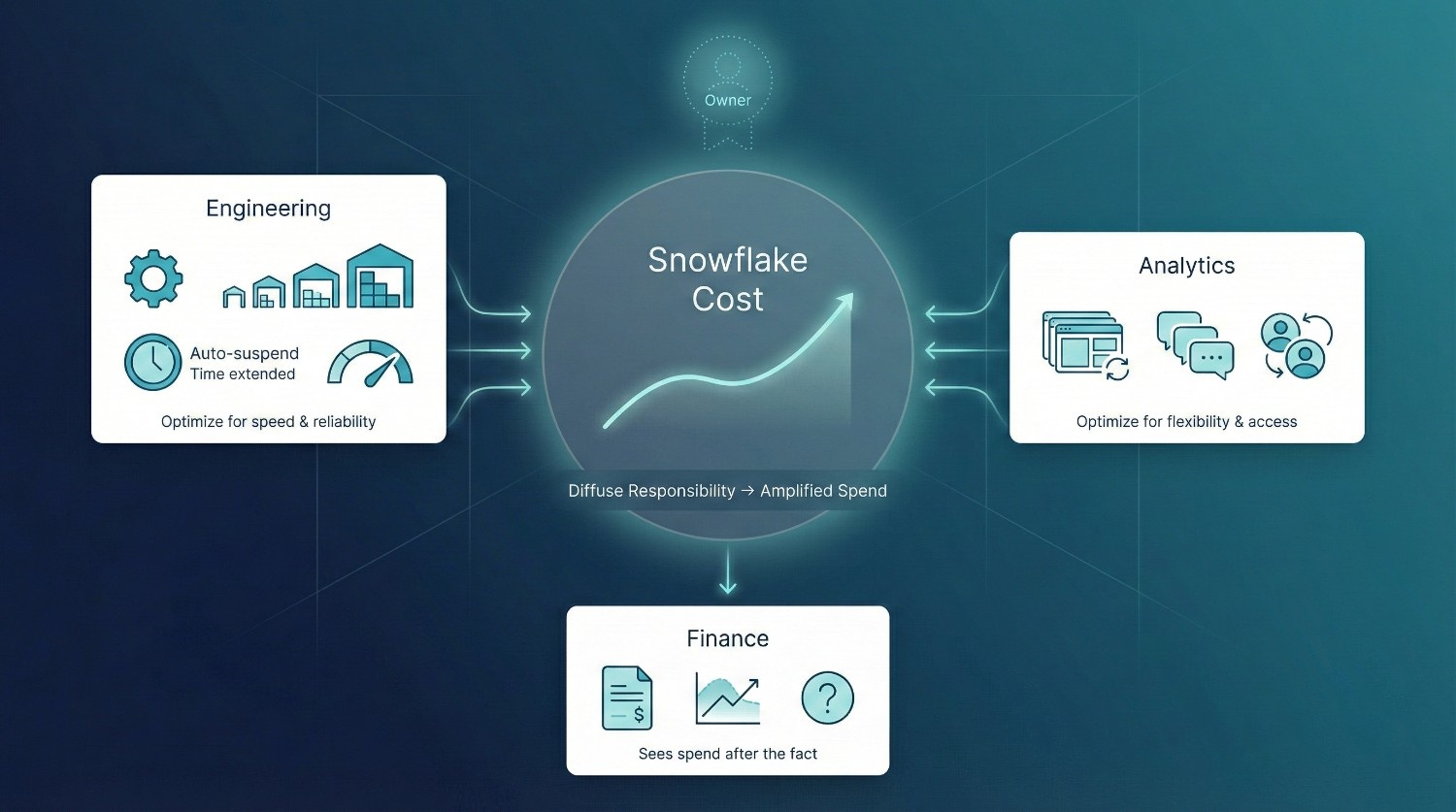

Lack of Cost Ownership Amplifies Surprises

Snowflake cost surprises are typically not caused by bad intent. They are frequently caused by diffuse responsibility. When no one clearly owns Snowflake cost end to end, every team makes reasonable local decisions, and the organization absorbs an unreasonable global outcome.

No Single Owner of Snowflake Cost

In many organizations:

- Engineering owns pipelines and performance

- Analytics owns dashboards and self-service

- Finance owns the invoice

But no one is explicitly accountable for the economic behavior of the platform.

Without a named owner:

- No one is responsible for tradeoffs between speed and spend

- No one arbitrates competing workload priorities

- No one feels accountable when usage patterns drift

Cost becomes everyone’s concern, and no one’s job. FinOps operating models recommend assigning cost accountability at the workload or domain level rather than at the infrastructure level to reduce ambiguity.

Engineering Optimizes for Speed

Engineering teams are typically measured on:

- Reliability

- Performance

- Delivery timelines

When faced with ambiguity, they choose:

- Larger warehouses to avoid complaints

- Longer auto-suspend times to prevent cold starts

- Shared compute to reduce operational complexity

These are rational technical choices. But they quietly increase Snowflake cost, often without engineers realizing the financial impact of each decision.

Analytics Optimizes for Flexibility

Analytics teams are rewarded for:

- Fast answers

- Self-service enablement

- Minimal friction

To achieve that, they:

- Refresh dashboards frequently

- Run validation queries repeatedly

- Explore data freely during investigations

Again, these behaviors are rational and valuable. But without constraints, flexibility turns into constant concurrency, and constant concurrency turns into cost.

Finance Sees the Bill Last

Finance typically enters the loop only when:

- The invoice arrives

- Spend exceeds forecast

- Leadership asks for explanations

At that point:

- The behavior has already happened

- The cost has already accrued

- The narrative is already defensive

Finance is forced into a reactive posture, questioning usage after the fact instead of shaping it beforehand. Organizations that implement shared cost dashboards between finance and engineering typically reduce reactive budget escalations within a few reporting cycles.

Why Surprises Are Inevitable Without Shared Ownership

Snowflake prices the intersection of engineering behavior, analytical behavior, and organizational trust. If ownership is split across silos:

- Each team optimizes locally

- No one optimizes globally

- Cost signals arrive too late

Surprises are not solely a failure of monitoring.

They are frequently a failure of ownership design.

The Core Insight

Snowflake cost cannot typically be governed by finance alone. It cannot typically be optimized by engineering alone. It cannot typically be controlled by analytics alone. It requires shared ownership with explicit decision rights:

- Who can create new workloads

- Who decides warehouse sizing standards

- Who approves prolonged dual-runs or backfills

- Who explains spend in business terms

Enterprise cloud governance frameworks consistently show that clearly defined decision rights reduce both cost variance and internal friction. Until Snowflake cost has a clear owner, or a clearly defined ownership model, surprises aren’t just possible. They’re inevitable.

Snowflake bills often do not creep up in a smooth, predictable line. They can move in noticeable steps. To finance teams, this feels like a surprise. To technical teams, it often feels confusing. In reality, Snowflake cost is behaving consistently with its usage based design..

Usage Grows Non-Linearly

Snowflake cost does not necessarily scale in a straight line with:

- Data volume

- Headcount

- Number of dashboards

Instead, it scales with how many workloads and queries overlap at the same time. A small increase in:

- Users

- Dashboards

- Ad-hoc exploration

can create a step-change in concurrency:

- More simultaneous queries

- More overlapping warehouse runtimes

- More credits burned per hour

From the outside, usage may appear steady.

From a billing perspective, cost can increase in step changes rather than gradually.

New Teams Onboard Quietly

New users rarely arrive with fanfare:

- A sales team gets access

- A marketing analyst starts exploring

- A product group builds their first dashboards

Each addition seems trivial in isolation. But each new team brings:

- Their own dashboards

- Their own refresh schedules

- Their own ad-hoc querying patterns

Snowflake cost doesn’t typically rise when access is granted alone. It rises when those teams begin working concurrently. Finance sees one consolidated bill. Snowflake sees many new behaviors. In multi domain data environments, user growth and dashboard proliferation are often leading indicators of future compute cost inflection points.

Self-Service Expands Rapidly

Self service adoption increases analytical surface area, which amplifies overlap and runtime sensitivity even when individual queries remain efficient. Self-service analytics is usually a success story:

- Fewer data team bottlenecks

- Faster insights

- More autonomy

But self-service changes cost dynamics:

- Queries are no longer coordinated

- Dashboards refresh independently

- Investigations trigger repeated re-runs

Usage doesn’t simply increase. It can compound through concurrency and overlap. This is why Snowflake cost often jumps shortly after self-service “takes off”, even if no one changed warehouse sizes or data volume.

Why the Jump Feels Abrupt

From a finance perspective:

- Spend was stable last month

- No major initiatives were announced

- Headcount didn’t double

So the invoice feels sudden. From Snowflake’s perspective:

- More concurrent users

- More overlapping workloads

- Longer warehouse uptime

The change was often not a single spike but a concurrency or runtime threshold crossing. |

Snowflake pricing is sensitive to:

- Concurrency thresholds

- Runtime overlap

- Behavioral tipping points

Once crossed, spend can move to a higher sustained baseline.

The Key Takeaway

Snowflake bills feel sudden because:

- Usage grows in steps, not slopes

- Behavior changes faster than forecasts

- Concurrency amplifies small decisions

Nothing necessarily went wrong. The system reached a new usage pattern. The way to reduce surprises isn’t limited to tighter billing reviews. It’s earlier visibility into how behavior is changing, before those thresholds are crossed.

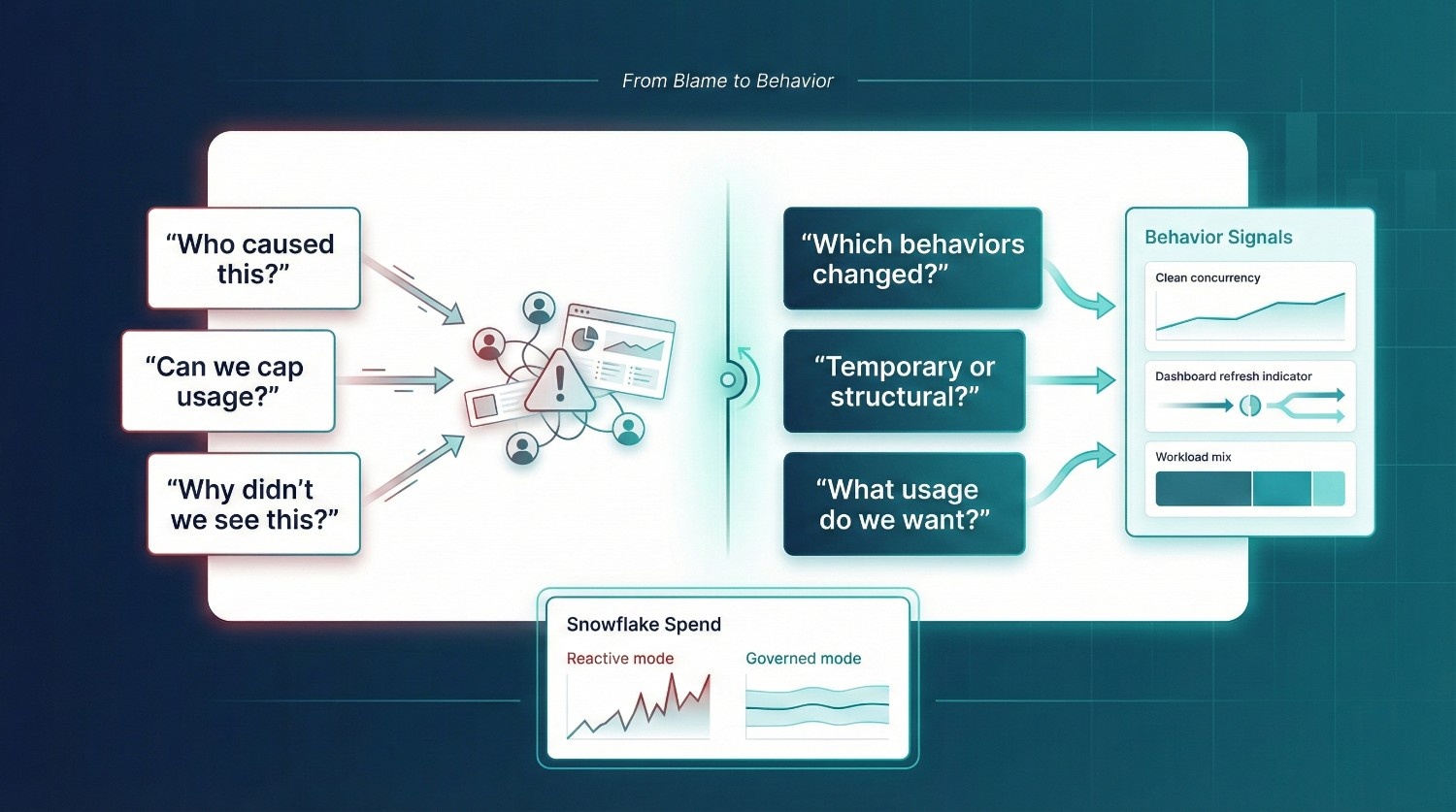

When a Snowflake bill is higher than expected, finance teams naturally look for accountability. The instinct is understandable, but the framing often leads to the wrong actions.

The Common Questions (and Their Limits)

“Who caused this spend?”

This assumes Snowflake cost is driven by individual mistakes. In reality, spend is usually the result of collective behavior: more users, more parallel work, more exploration. Finger-pointing discourages transparency and pushes usage into the shadows.

“Can we cap usage?”

Hard caps feel like control, but they usually backfire. Teams delay work, dashboards break, or analytics moves off-platform. Cost becomes “managed,” but business value drops with it.

“Why didn’t we see this coming?”

This assumes the issue was a forecasting failure. More often, it’s a visibility failure. Usage patterns changed gradually, but no one was watching behavior-level signals like concurrency, re-runs, or new workload types.

These questions focus on blame and restriction. They may temporarily reduce visible spend, but they rarely reduce long term surprise and often damage trust between finance and data teams. Industry cost governance reviews consistently show that organisations that focus first on behaviour diagnostics rather than budget enforcement reduce variance faster and preserve cross functional trust more effectively.

Better Questions That Actually Create Control

“Which behaviors drove this spend?”

Look at what changed, not who. Examples:

- More concurrent users?

- New dashboards refreshing frequently?

- Analysts running repeated exploratory queries?

Behavior explains cost far better than invoices.

“Which costs are temporary vs structural?”

Not all Snowflake cost is equal.

- Temporary: migrations, backfills, validation, experimentation

- Structural: steady BI usage, recurring ELT jobs, self-service analytics

This distinction prevents overreacting to short-term spikes. FinOps frameworks emphasize separating structural spend from transitional activity before making optimization decisions, since conflating the two often leads to cutting productive growth along with temporary overhead.

“What usage do we want to encourage?”

This reframes cost as an investment question.

- Do we want faster self-service analytics?

- More experimentation?

- Broader access to data?

Once finance and leadership agree on desired behavior, governance can reinforce it instead of fighting it.

The Core Shift

Snowflake cost cannot be managed by asking:

“How do we stop people from using data?”

It can be managed by asking:

“How do we guide usage toward the outcomes we actually want?”

That shift, from control to intentional behavior, is where predictable Snowflake cost really starts.

How Finance Teams Can Prevent Future Snowflake Cost Surprises

Snowflake cost surprises often begin weeks earlier, when usage patterns change without corresponding visibility or ownership. Preventing surprises isn’t about tighter approvals or more aggressive cost cutting. It’s about giving finance early signal, shared context, and practical levers, before spend locks in. Here’s what actually works.

Cost Visibility by Warehouse and Workload

Finance teams can’t manage what they can’t see. Snowflake cost should be visible by:

- Warehouse (BI, ELT, ad-hoc, data science)

- Workload type (dashboards, exploration, backfills)

- Owning team or function

This matters because:

- Different workloads have very different cost profiles

- Some are essential and recurring

- Others are experimental or temporary

When cost is only viewed as a single monthly number, every increase looks suspicious. When it’s broken down by workload, changes become explainable. Visibility turns “Why is this higher?” into “This grew because usage changed here.”

Forecast Ranges, Not Single Numbers

Single-number forecasts create false certainty, and guaranteed disappointment. Snowflake cost should be forecasted as ranges:

- Conservative scenario

- Expected scenario

- High-usage (but plausible) scenario

Why this works:

- Snowflake spend is primarily behavior-driven, not fixed

- Adoption, self-service, and experimentation are hard to pin to one number

- Ranges normalize variance instead of framing it as failure. Scenario based forecasting is particularly effective in usage based platforms because it aligns financial planning with behavioral variability rather than assuming static consumption patterns.

Finance teams don’t need perfect predictions.

They need bounded outcomes they can plan around.

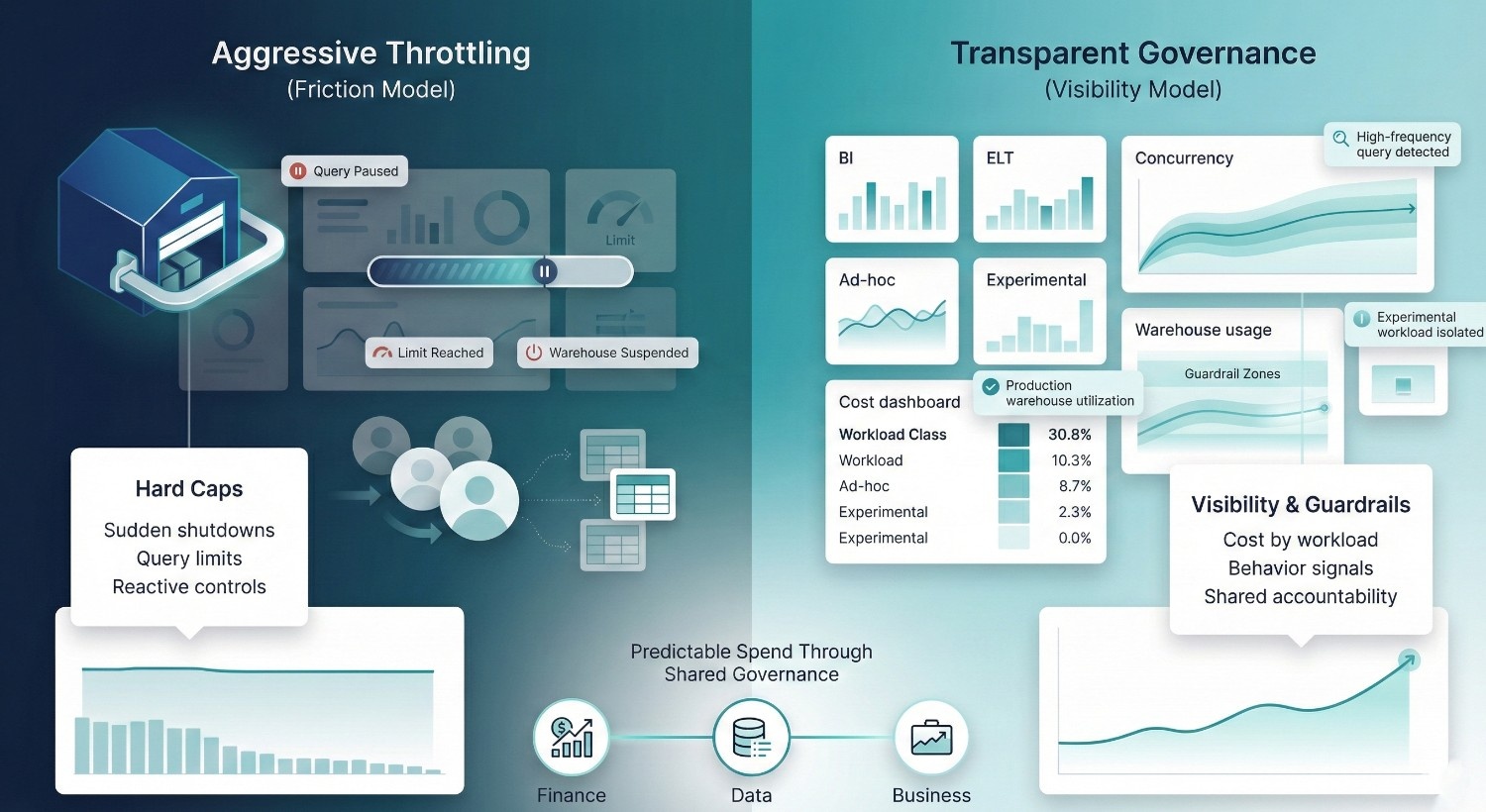

Guardrails Instead of Hard Caps

Hard caps feel like control, but they usually:

- Break dashboards

- Interrupt critical work

- Push teams to find workarounds

Guardrails tend to work better in adoption heavy environments because they guide behavior without fully stopping it. Effective guardrails include:

- Warehouse-level spend thresholds

- Alerts when concurrency or runtime spikes

- Separate limits for experimental vs production workloads

The goal isn’t to block usage. It’s to surface when usage patterns change, while there’s still time to respond. Organizations that implement behavioral alerts instead of hard ceilings typically achieve higher adoption and lower surprise variance because intervention happens earlier and with context.

Regular Finance Data Reviews

Snowflake cost governance fails when finance only enters the conversation after the bill arrives. Short, recurring reviews change that dynamic:

- What changed this period?

- Which costs were expected vs unexpected?

- Which workloads are growing, and why?

- What upcoming initiatives could shift usage?

These reviews don’t need to be heavy. They need to be predictable and cross-functional. When finance understands why cost moved, and data teams understand how cost is perceived, surprises disappear. Cross functional review cadence is one of the strongest predictors of stable cloud spend because it creates shared narrative before variance becomes political

The Core Principle

Snowflake cost control works best before invoices arrive, not after. Finance teams prevent surprises when they:

- Watch behavior, not just spend

- Expect variability instead of fighting it

- Share ownership instead of enforcing limits

Snowflake isn’t unpredictable. It’s just honest about how people use data. The earlier finance sees that behavior, the fewer surprises there are to explain later.

Snowflake Cost Control Without Slowing the Business

The fastest way to “control” Snowflake cost is also the most damaging one: aggressive throttling. It looks decisive on paper. In practice, it quietly undermines the very outcomes Snowflake was adopted to enable.

Why Aggressive Throttling Backfires

Hard restrictions such as tight caps, sudden warehouse shutdowns, or strict query limits often create immediate friction:

- Dashboards fail during peak hours

- Analysts delay or abandon analysis

- Teams revert to spreadsheets or shadow systems

The organization learns a dangerous lesson:

Using data is risky.

Cost may flatten temporarily, but trust and adoption decline. Over time, business teams stop relying on Snowflake altogether, or find ways around controls that make cost harder to see, not easier to manage.

How Transparency Changes Behavior

The most effective cost control tool isn’t restriction. It’s visibility. When teams can see:

- Which workloads consume the most credits

- How concurrency and re-runs affect cost

- What their queries actually cost to run

Behavior changes naturally:

- Expensive queries get reused instead of rerun

- Dashboards are rationalized

- Experimental work is isolated from production

People don’t need to be told to “use less.” They need to understand what their usage does.

Shared Accountability Instead of Policing

Snowflake cost problems intensify when:

- Finance owns the bill

- Engineering owns the system

- Analytics owns the usage

and no one owns the outcome. Shared accountability works better:

- Finance frames cost in business terms

- Data teams design guardrails and visibility

- Business teams understand the cost of their decisions

Cost becomes a collective trade-off, not a compliance issue. Mature data organizations treat platform spend as a portfolio of intentional trade offs rather than as an operational leak to be patched reactively.

Optimize for Predictability, Not Minimal Spend

The goal of Snowflake cost control isn’t the lowest possible bill. It’s:

- Predictable spend

- Explainable variance

- Confidence that cost aligns with value

An organization that understands and governs its usage may spend more than one that throttles aggressively, but it will extract far more value per credit.

The Bottom Line

Snowflake cost control succeeds when it:

- Preserves access to data

- Encourages responsible usage

- Makes trade-offs visible

Control that slows the business isn’t control, it’s avoidance. The strongest signal of mature Snowflake governance isn’t how little you spend. It’s how confidently you can explain why you’re spending it. Executive alignment around cost philosophy is often a more reliable indicator of long term efficiency than the absolute size of the monthly invoice

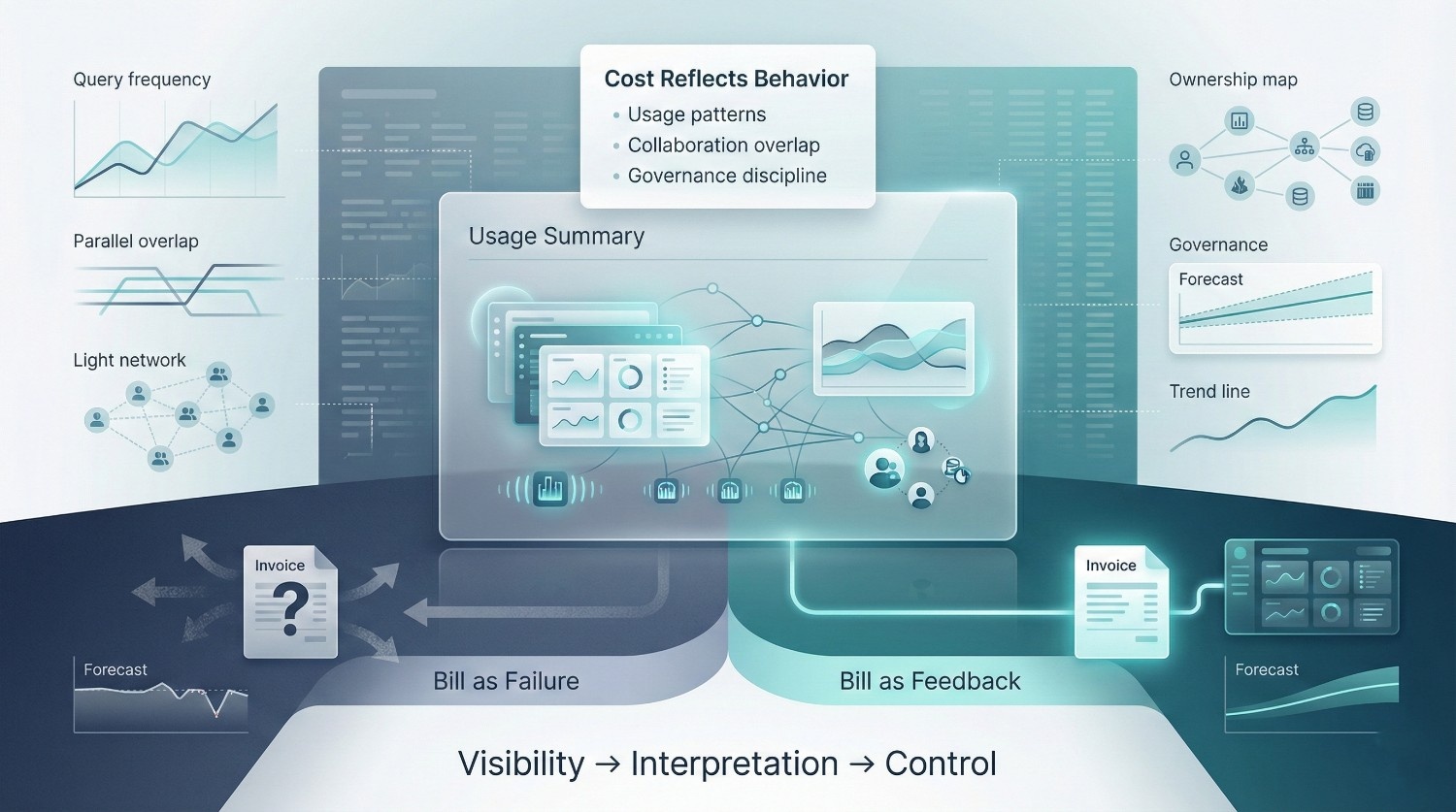

Final Thoughts

Snowflake bills are not automatically a sign that something went wrong. They often signal that usage patterns have become visible. Snowflake cost reflects:

- How data is actually used, not how teams assume it’s used

- How teams collaborate, coordinate, and overlap in their work

- How decisions are governed, owned, and prioritized

When spend increases, Snowflake isn’t necessarily exposing waste by default. It’s exposing behavior. That’s why Snowflake bills feel confronting to finance teams. They reveal:

- Where usage is unstructured

- Where ownership is unclear

Where growth is happening faster than governance

Final Takeaway

Finance teams are often surprised not by Snowflake itself, but by previously unexamined usage patterns across the organization. The choice isn’t whether Snowflake cost will reflect behavior. It always will. The real choice is whether leadership:

- Treats the bill as a failure to explain

- Or as feedback to act on

Organizations that treat Snowflake bills as feedback gain predictability, confidence, and control. Behavior visible through billing data becomes an advantage when leadership uses it as an early signal of adoption and governance maturity rather than as a lagging indicator of failure. Those that treat them as failures keep getting surprised, month after month.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Because Snowflake prices behavior, not assets. Costs change when usage patterns shift, more users, more concurrency, more re-runs, not when headcount or data volume visibly changes. Those behavior shifts often happen weeks before finance sees the invoice.

Not necessarily. Higher spend can come from:

- More teams using data productively

- Expanded self-service analytics

- Temporary workloads like migrations or backfills

The real question isn’t “Is spend higher?” but “What behavior caused it, and is that behavior intentional?”

Because “use” in Snowflake includes:

- Warehouses running concurrently

- Queries being re-run repeatedly

- Idle compute staying active longer than expected

Small inefficiencies compound quickly, making spend feel jumpy even when no single action seems large.

Yes, but not through hard caps or aggressive throttling. Effective control comes from:

- Visibility by warehouse and workload

- Guardrails and alerts instead of shutdowns

- Shared ownership between finance, data, and business teams

Control works best when it guides behavior rather than punishes usage.

Because usage grows in steps, not smooth curves. Adding a few users or dashboards can push concurrency past a threshold, moving spend to a new plateau. From finance’s view it’s a spike; from Snowflake’s view it’s a new usage pattern.

Not always. Many spikes are temporary:

- Migration dual-runs

- Validation and reconciliation work

- Backfills and reprocessing

Without context, finance teams often assume these are structural increases when they’re actually time-bound.

Snowflake cost should be co-owned:

- Finance owns predictability and framing cost in business terms

- Data teams own system design, guardrails, and visibility

- Business teams own usage decisions and trade-offs

When only one group owns cost, surprises are inevitable.

Treating the bill as an error to correct instead of feedback to understand. Snowflake surfaces usage patterns directly through metered billing, which can make behavioral shifts more visible than in fixed capacity systems. Ignoring that signal, or reacting with blunt restrictions, leads to worse outcomes over time.

Not minimal spend. The real goals are:

- Predictable spend

- Explainable variance

- Clear alignment between cost and business value

A mature organisation may spend more, but will rarely be surprised.

As feedback, not failures. Snowflake bills show:

- How teams actually work

- Where governance is strong or weak

- Where growth is happening faster than structure

Organisations that treat that feedback seriously stop being surprised. Those that don’t keep asking the same question every month: “Why is this higher than expected?”