Table of Contents

Introduction

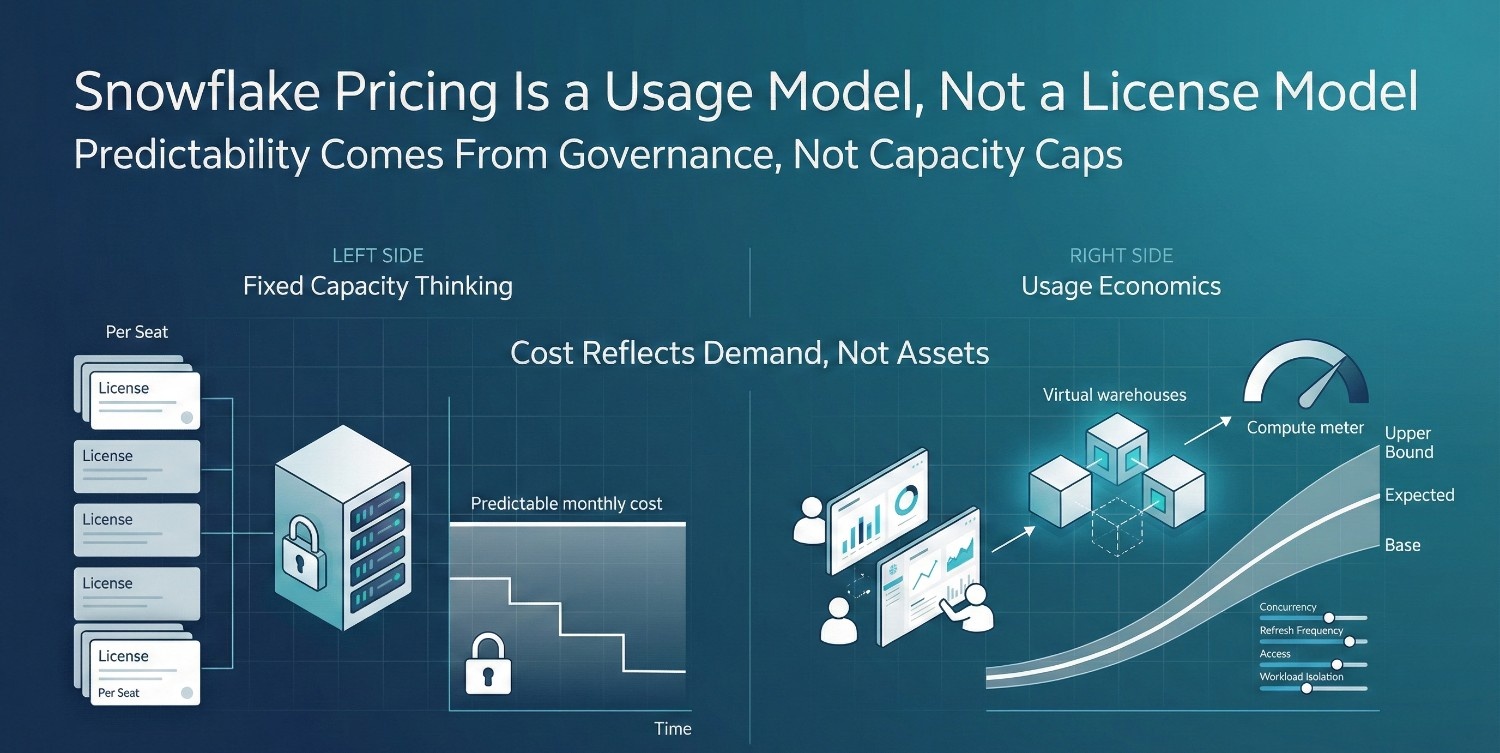

For most CFOs, Snowflake pricing does not feel like pricing at all. There are no fixed licenses. No clear “per user” cost. No predictable capacity commitments tied neatly to a budget line.

Instead, Snowflake shows up as a usage-based expense that grows and shrinks with behavior, often faster than finance teams are used to seeing in core IT systems. That unfamiliarity is where anxiety begins. This mirrors patterns seen with other consumption-based platforms, where financial risk shifts from procurement to operational behavior.

Why Snowflake Breaks Traditional IT Cost Models

Most enterprise technology fits into patterns finance teams understand:

- Licenses per seat

- Fixed infrastructure contracts

- Predictable depreciation curves

Snowflake does not follow those rules. With Snowflake, cost is driven by:

- When compute runs

- How large it is when it runs

- How often people and systems trigger it

There’s no fixed ceiling by default. Spend expands and contracts with usage, which makes Snowflake feel less like a fixed system and more like an open meter. That’s not a flaw. It is the economic model. This design aligns cost directly with demand, removing the buffer that traditionally obscured inefficient or unexpected usage.

Why Snowflake Cost Feels Unpredictable

From a finance perspective, Snowflake cost often feels unpredictable because:

- Usage patterns change faster than budgets

- New teams can consume compute without new contracts

- Growth shows up immediately in spend, not months later

What feels like volatility is often just increased visibility. Snowflake makes usage explicit instead of hiding it inside fixed infrastructure. In fixed-capacity environments, usage spikes are often absorbed silently until renewal or upgrade cycles. Snowflake exposes them immediately.

Why Cost Attribution Feels Hard

Attribution is difficult when:

- Multiple teams share the same compute

- Queries mix exploration, production, and validation

- No single owner is accountable for usage

The bill arrives as a total number, while the behavior that created it is distributed across engineering, analytics, and business teams. Without structure, Snowflake cost looks collective and therefore unmanageable. Shared infrastructure without shared accountability is one of the most common causes of perceived cost loss of control.

Why Governance Feels Elusive

Traditional governance relies on:

- Approval gates

- Capacity planning

- Fixed limits

Snowflake’s elasticity bypasses those controls. Teams do not need approval to scale usage, they just run more queries. When governance is not redesigned for this model, finance experiences Snowflake as:

- Reactive instead of controlled

- Transparent but not explainable

- Accountable in theory, diffuse in practice

This gap is not caused by lack of controls, but by controls designed for capacity-based systems being applied to usage-based ones.

The Core Reframe CFOs Need

Here’s the key shift:

Snowflake pricing is not a technology problem. It is a usage economics problem.

Snowflake does not charge for owning infrastructure.

It charges for how the organization behaves around data. That means:

- Cost reflects demand, not assets

- Spend signals adoption, not inefficiency by default

- Control comes from shaping behavior, not restricting access

This is why governance, modeling discipline, and workload design directly influence financial outcomes.

What This Article Will Help CFOs Do

This guide is designed to give CFOs leverage, not technical detail. It will help you:

- Understand the real drivers of Snowflake cost (beyond “credits”)

- Ask better questions of engineering and data teams

- Control spend without slowing decision-making or undermining trust

Snowflake cost does not need to feel unfamiliar or risky. With the right forecasting and governance model, usage-based spend can be easier to manage than fixed-capacity infrastructure. But it does require finance to engage with it differently than legacy IT spend.

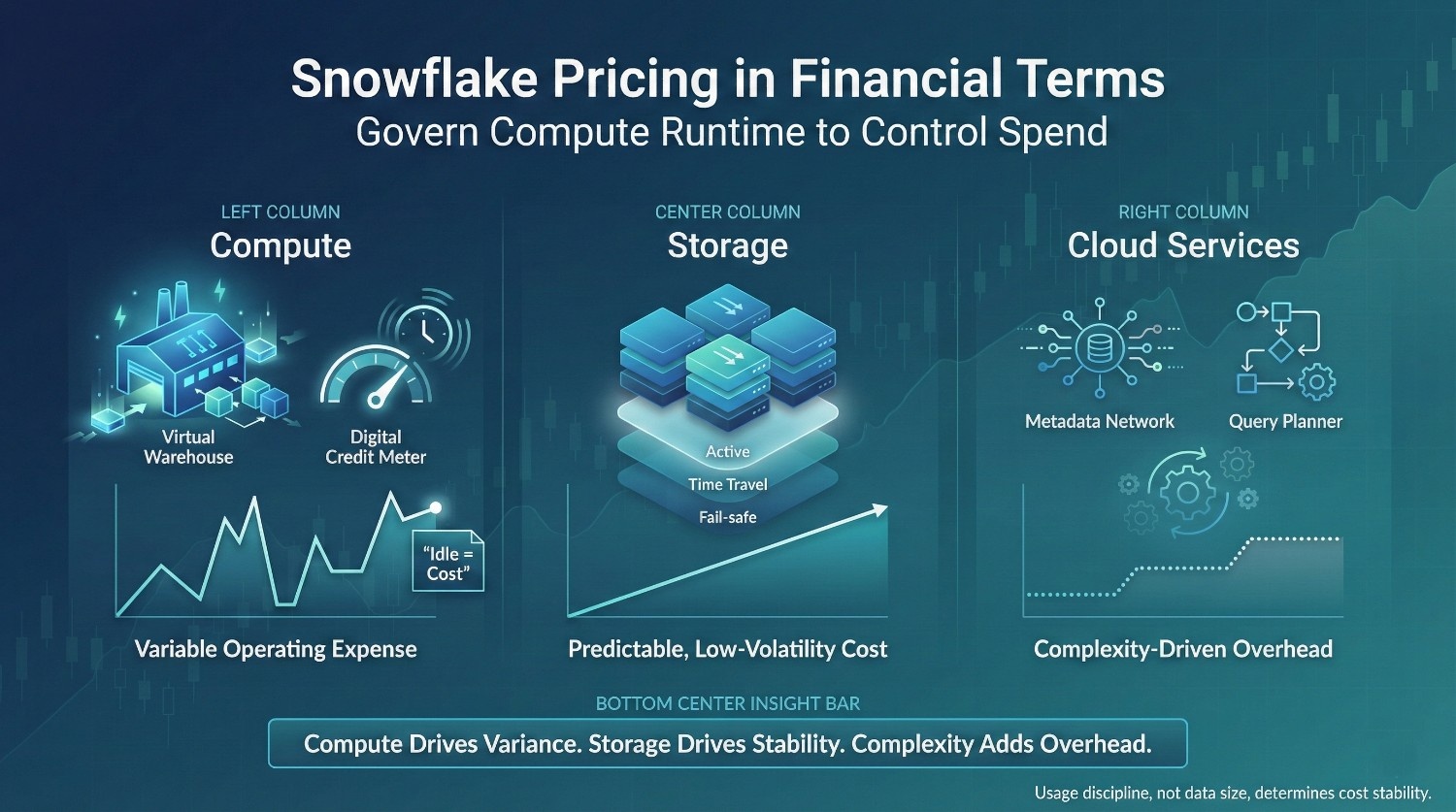

The Snowflake Pricing Model in Plain Financial Terms

To make Snowflake cost governable, CFOs do not need technical depth, they need the right economic framing. Snowflake pricing has three components. Only one of them behaves in a way that usually causes budget concern.

Compute: Variable Operating Expense

Compute is where Snowflake cost lives, and where finance attention should focus.

Think of virtual warehouses as on-demand factories:

- They consume credits while they are running

- They scale up and down instantly

- They stop costing money only when they shut off

Snowflake charges per second of usage, based on warehouse size. What matters financially:

- Larger warehouses burn credits faster

- Warehouses burn credits even when idle

- Short periods of inefficiency compound quickly

This is not capital expenditure. It behaves as a variable operating expense. This aligns Snowflake compute more closely with other consumption-based operating costs, such as cloud networking or transaction-based SaaS fees.

The key risk for finance is not “inefficient queries”, it is unmanaged runtime. Idle compute is real money, even if no value is being produced during that time.

Storage: Predictable, Low-Volatility Cost

Storage behaves very differently, and much more comfortably, from a finance perspective. Snowflake storage is:

- Compressed

- Columnar

- Linearly priced

It includes:

- Active data

- Time Travel (historical versions)

- Fail-safe (short-term recovery layer)

Why storage is rarely the main budget risk:

- Growth is gradual and visible

- Costs scale with data volume, not user behavior

- Spend changes are easy to forecast

Storage cost growth is typically visible months in advance, making it one of the least surprising components of Snowflake spend. If Snowflake storage is driving financial concern, it often signals:

- Excessive retention policies

- Rebuildable data being stored permanently

This is typically a retention or data lifecycle issue, not a pricing problem.

Cloud Services: The Least Understood Line Item

Cloud services cost often confuses finance teams because it does not behave like compute or storage.

It covers:

- Metadata management

- Query optimization and planning

- Access control and coordination

What’s important financially:

- It is not tied to warehouse runtime

- It grows with complexity and activity, not raw data size

- High query volumes and frequent schema changes increase it

Environments with heavy automation, orchestration, or frequent metadata churn tend to notice this line item sooner than others. For most organizations, cloud services spend is modest.Ignoring it entirely creates unexplained variance that undermines confidence in forecasts.

The Financial Takeaway

Snowflake pricing becomes understandable when re-framed as:

- Compute: variable operating expense driven by behaviour

- Storage: predictable, low-volatility cost

- Cloud services: complexity-driven overhead

For CFOs, the control lever is clear:

Snowflake cost is governed primarily by when compute runs, how long it runs, and who triggers it. That’s not a technical issue.

It is an operating discipline issue, one finance leaders are well-positioned to influence once the model is understood. This is why organizations that treat Snowflake cost as an operating model tend to achieve stability faster than those that focus only on technical tuning.

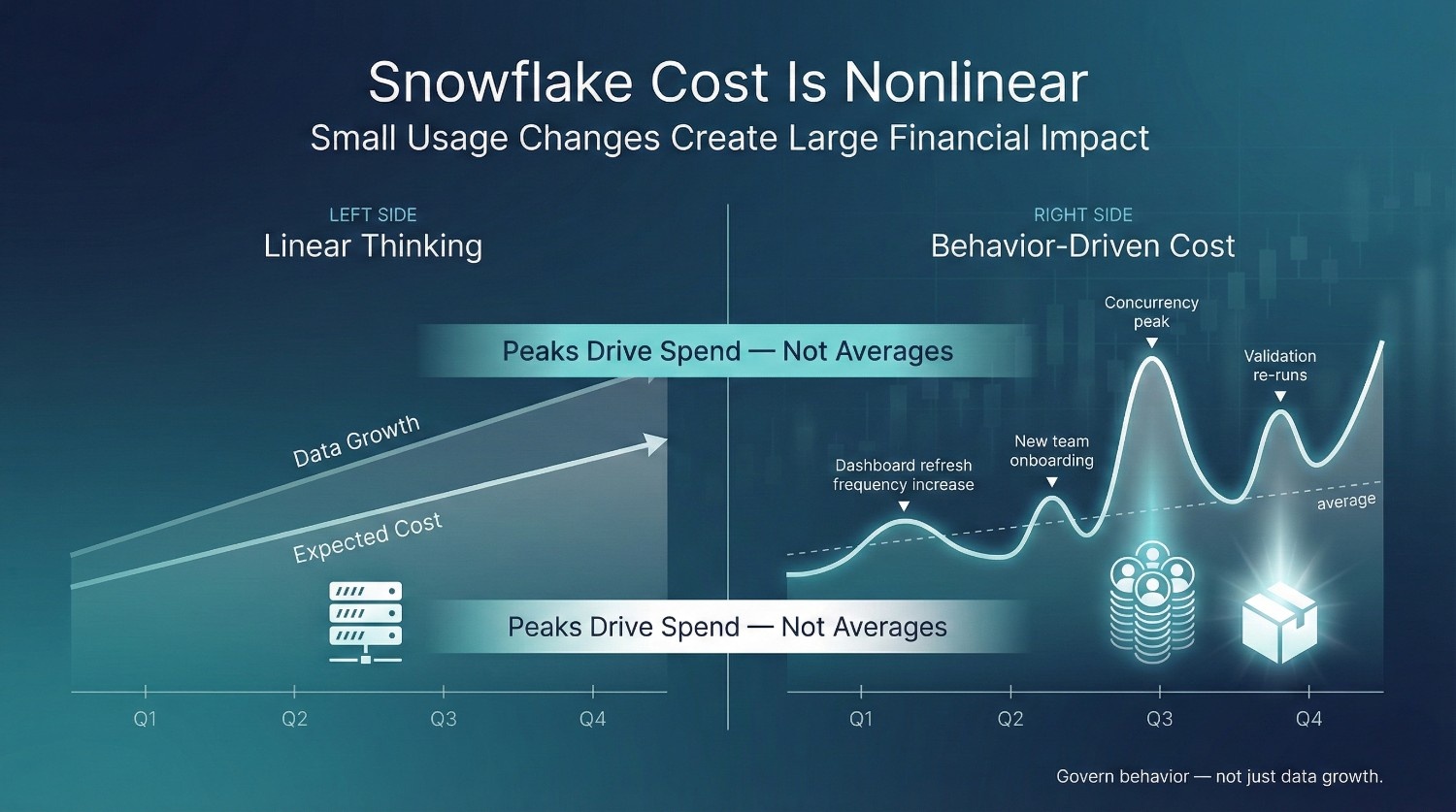

Why Snowflake Cost Is Not Linear

One of the biggest traps CFOs fall into is assuming Snowflake cost scales smoothly with growth. It does not. Snowflake cost behaves more like a nonlinear operating expense than a traditional IT budget line.

Doubling Data ≠ Doubling Cost

In traditional systems, more data usually meant more hardware, and higher fixed cost. In Snowflake:

- Data volume mainly affects storage (predictable)

- Compute cost depends on how often data is processed, not how much exists

You can double your data and see minimal cost change, or keep data flat and watch spend spike.

The difference is behavior, not scale. This is a direct consequence of Snowflake separating storage from compute and charging compute only when it is actively used.

Small Behavior Changes Can Spike Spending

Snowflake cost is sensitive to how people and systems use it. Examples CFOs should recognize:

- A dashboard refresh moving from hourly to every 5 minutes

- A new team running the same analysis independently

- Validation queries being re-run during investigations

- Analysts sharing a warehouse during peak hours

None of these feel dramatic in isolation. Together, they change cost materially, without any infrastructure change. Finance teams often perceive this as volatility, but it is simply rapid feedback between usage decisions and spend.

What Actually Drives Snowflake Cost

Snowflake cost is primarily driven by three interacting forces:

Query frequency

How often queries run matters more than how complex they are. Repetition compounds cost faster than one-time work.

Concurrency

Multiple users and systems running queries at the same time extend warehouse runtime and trigger scaling behavior.

Organizational habits

Low trust, unclear ownership, and duplicated work lead to re-runs, parallel logic, and unnecessary compute.

This is why two teams with the same data can have radically different Snowflake bills. The variance usually reflects differences in workflow design, trust in shared models, and workload isolation rather than technical efficiency.

Why “Average Cost” Projections Are Dangerous

Average-based projections hide risk. They assume:

- Smooth usage patterns

- Stable behavior

- Even distribution of queries

Real usage is spiky. Peaks, not averages, drive cost. This mirrors how cloud networking, payments, and other usage-based operating expenses behave under bursty demand. CFOs should be skeptical of forecasts that say:

“On average, Snowflake will cost X per month.”

The right question is:

“What behaviors push us above that average, and how likely are they?”

The CFO-Level Insight

Snowflake cost does not grow linearly because organizations do not behave linearly. Understanding this shifts the finance conversation:

- From budgeting for capacity

- To governing behavior

That’s the mindset required to control Snowflake cost without constraining value.

The Biggest Snowflake Cost Drivers CFOs Should Watch

From a finance perspective, the most important thing to understand is this:

Snowflake cost is not driven by technology choices alone. It is driven by how people work with data, day to day.

The biggest cost drivers are behavioral patterns that become expensive at scale if they are left unmanaged.

Over-Provisioned Warehouses

This is the most common and least controversial issue.

It happens when:

- Warehouses are sized for peak demand and used for average workloads

- Large warehouses stay running for light queries

- Sizes are never revisited once “things work”

Financial impact:

- Credits are burned faster than necessary

- Cost inflation becomes the baseline, not an exception

Bigger warehouses do not automatically produce proportional value.They primarily increase the credit burn rate. In many environments, query performance plateaus well before warehouse size does, making excess capacity a pure cost premium.

Too Many Users on Shared Compute

Shared compute feels efficient, but it hides risk. When many users share the same warehouse:

- Concurrency increases runtime

- Warehouses stay active longer

- Scaling behavior triggers unexpectedly

From finance’s view, this looks like:

- Cost spikes with no obvious change in headcount or data volume

The issue is not usage. It is unstructured usage. Without workload separation, finance sees variability without a clear causal link to business activity.

Unrestricted Ad-Hoc Querying

Ad-hoc analysis creates value, but without guardrails, it becomes unpredictable spend. Common patterns:

- Analysts re-running similar queries repeatedly

- Exploratory work happening on production warehouses

- Validation queries during investigations multiplying compute usage

None of this is misuse. Without norms, however, it becomes financially opaque. Finance teams struggle not because spend exists, but because the drivers of that spend are unclear.

Duplicate Dashboards and Reports

This is a hidden but significant driver. It happens when:

- Teams do not trust shared metrics

- Each group builds its own version of “the same” report

- Dashboards recompute similar logic independently

Financial impact:

- The same transformations run dozens of times

- Compute cost grows without increasing insight

Duplicate reporting is a trust problem that carries a direct cost. When teams trust shared definitions, query volume naturally converges instead of multiplying.

Long-Running or Frequently Re-Run Queries

CFOs often hear about “expensive queries.” The real issue is usually frequency, not size. Cost risk increases when:

- Medium-cost queries run constantly

- Dashboards refresh aggressively

- Investigations trigger repeated re-runs

Repetition compounds cost far faster than occasional heavy analysis. High-frequency workloads should always be scrutinized more closely than one-off analytical queries.

The Key Insight CFOs Should Anchor On

Snowflake cost reflects:

- How often people ask questions

- How confident they are in shared answers

- How coordinated teams are around data

It is not just a systems problem, it is a work pattern problem. For CFOs, that’s good news. It means Snowflake cost is not an uncontrollable cloud tax. It is a governed operating expense, once the right behaviors are made visible and intentional. When cost drivers are observable and attributable, finance can manage Snowflake spend using the same discipline applied to other variable operating expenses.

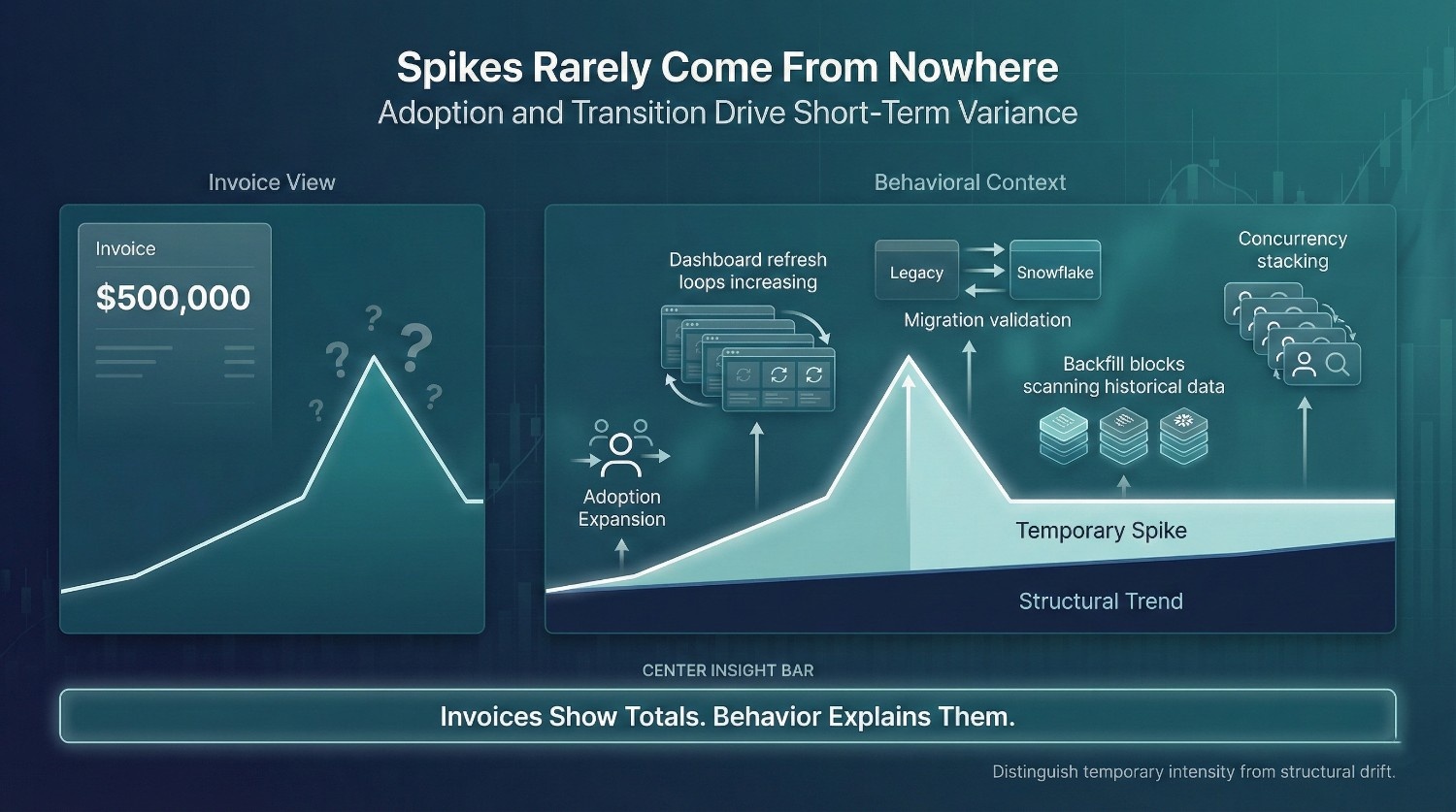

Why Snowflake Cost Spikes Often Appear “Out of Nowhere”

From a finance seat, Snowflake cost spikes often look sudden, and unjustified.

Nothing obvious changed:

- Headcount is stable

- Data volume did not explode

- No new contract was signed

Yet the invoice jumps. In most cases, the spike did not come from nowhere. It came from the context the invoice does not show. In usage-based systems, cost changes often reflect behavioral shifts that are invisible at the invoice level.

New Teams Get Onboarded

Snowflake adoption tends to spread organically. A few early teams start using it. Results look good. Access expands.

What changes financially:

- More concurrent users

- More overlapping queries

- More dashboards refreshing independently

None of this requires procurement approval. Usage expands by design in consumption-based platforms. From finance’s perspective, cost rises without a clear “event,” because the event was adoption, not infrastructure. This is a common pattern in modern cloud platforms, where growth happens through access expansion rather than formal capacity changes.

Self-Service Analytics Expands

Self-service is one of Snowflake’s biggest value drivers, and one of its biggest cost accelerators. As self-service grows:

- Analysts explore more freely

- Business users run their own queries

- Validation and “just checking” behavior increases

This is not misuse. It is a success. Without guardrails, however, self-service converts curiosity directly into compute spend. Finance sees a spike; the organization sees empowerment. Both perspectives are valid. The gap arises when empowerment is not paired with cost-aware usage patterns. Both are true.

Migration Validation and Backfills

During and after migration, usage is temporarily intense. Typical drivers:

- Dual-running legacy systems and Snowflake

- Reconciliation queries to build confidence

- Backfills when logic changes

- Reprocessing historical data

These activities:

- Run on large warehouses

- Scan large volumes

- Occur in concentrated time windows

They are expected, but often missing from financial forecasts. When these temporary spikes are not labeled as such, they’re mistaken for a new steady-state cost.

Temporary Spikes Get Misread as Permanent Trends

This is where finance concern escalates unnecessarily. Without context:

- A one-time validation spike looks like runaway spend

- Backfill-heavy months distort averages

- Leadership assumes the worst-case is the new normal. Without explicit explanation, finance teams naturally extrapolate recent spend forward.

The problem is not the spike. It is the absence of narrative explaining why it happened and whether it will repeat.

Why Finance Needs Context, Not Just Invoices

Snowflake invoices answer one question:

“How much did we spend?”

They do not answer:

- What behavior caused the spend

- Whether it was planned or temporary

- Which teams or activities drove it

- Whether it created lasting value

In usage-based models, invoices lag behavior. Governance must operate earlier than billing cycles.

The CFO-Level Insight

Snowflake cost spikes usually signal:

- Adoption inflection points

- Transitional phases (like migration)

- New analytical behavior

They are not inherently failures. For finance leaders, the goal is not to eliminate spikes. It is to distinguish expected spikes from structural drift. Predictable spikes can be budgeted for. Structural drift requires intervention. That distinction only exists when cost is discussed alongside usage, behavior, and intent, not just totals on an invoice.

Snowflake Cost vs Business Value

One of the most damaging assumptions in cloud cost management is this:

- Low cost means success

- High cost means waste

In Snowflake, both assumptions are often wrong.

Low Cost ≠ High Value

A low Snowflake bill can mean:

- Underutilized data

- Slow decision cycles

- Teams avoiding analytics because it is inconvenient

- Data teams acting as bottlenecks instead of enablers

From a business perspective, this is not efficiency, it is missed leverage. In finance terms, low spend with low utilization often signals underinvestment rather than efficiency.

If Snowflake is cheap because:

- Dashboards are not trusted

- Self-service hasn’t materialized

- Decisions still rely on spreadsheets

then cost control has come at the expense of value creation.

High Cost ≠ Waste

Likewise, a higher Snowflake bill does not automatically signal inefficiency. Higher cost often reflects:

- Faster reporting cycles

- Broader self-service adoption

- More experimentation and exploration

- Decisions being made with data instead of instinct

The critical question is not how much Snowflake costs, but what that spend enables. In variable operating models, higher spend can be a leading indicator of adoption and decision velocity rather than waste.

A Better Framing for Finance

CFOs gain real leverage when they shift the conversation from absolute cost to cost per outcome. More meaningful lenses include:

Cost per decision

- What does it cost to answer a meaningful business question?

- Is that cost decreasing as models stabilize and reuse increases?

Cost per report

- Are core reports cheap and repeatable?

- Or are they recomputed differently by every team?

Cost per insight

- Is spend producing new understanding and better choices?

- Or just more activity without clarity?

These metrics do not require perfect precision. They require intentional framing. Directional consistency over time matters more than point-in-time accuracy for executive decision-making.

Why Blanket Cuts Backfire

When finance responds to rising Snowflake cost with blanket reductions:

- Warehouse sizes are cut indiscriminately

- Dashboards slow down

- Analysts lose trust in the platform

The result:

- Shadow systems reappear

- Manual work increases

- True organizational cost rises, even if Snowflake spend falls

Cost is reduced on paper, but value is destroyed in practice. These secondary costs often surface later as slower decisions, duplicated work, or increased manual reconciliation.

What CFOs Should Push For Instead

Rather than asking:

“How do we lower Snowflake cost?”

CFOs should ask:

“Which Snowflake spend produces durable business value, and which does not?”

That question drives:

- Better modeling decisions

- Clearer ownership

- Reuse instead of duplication

- Predictable, defensible spend

Framing spend in terms of durability helps distinguish temporary exploration from repeatable value creation.

The Core Insight

Snowflake cost is not a goal to minimize. It is a signal to interpret. Signals only become actionable when they are tied to outcomes, ownership, and repeatable behavior.

When finance frames Snowflake spend in terms of value per outcome, the conversation shifts:

- From restriction to prioritization

- From fear to governance

- From reactive cuts to deliberate tradeoffs

That’s how Snowflake cost becomes a managed investment, not an anxiety-inducing expense.

Budgeting for Snowflake

Traditional IT budgeting assumes stability in how technology is consumed over time:

- Fixed capacity that is purchased in advance

- Predictable utilization tied to that capacity

- Clear cost ceilings established at procurement time

Snowflake breaks those assumptions. It is elastic by design. That elasticity creates both value and financial risk. Elastic pricing shifts financial control from procurement decisions to ongoing operating behavior.

Why Hard Budget Caps Often Backfire

Fixed monthly caps feel safe to finance, but they create unintended behavior. When teams hit hard limits:

- Queries are throttled mid-analysis

- Dashboards slow or fail

- Analysts work around the system instead of within it

What follows:

- Shadow tools reappear

- Manual extracts increase

- True cost shifts outside Snowflake, not away from it

Cost avoidance often reappears as shadow infrastructure, manual work, or slower decision cycles.

Hard caps also create perverse incentives:

- Teams rush work at month-end

- Spend is optimized for invoices, not outcomes

Cost becomes a blocker rather than a signal

Smarter Budgeting Approaches CFOs Should Prefer

The goal is not to eliminate spend variability, it is to make it understandable and intentional. Variability becomes manageable when its drivers are visible and agreed upon in advance.

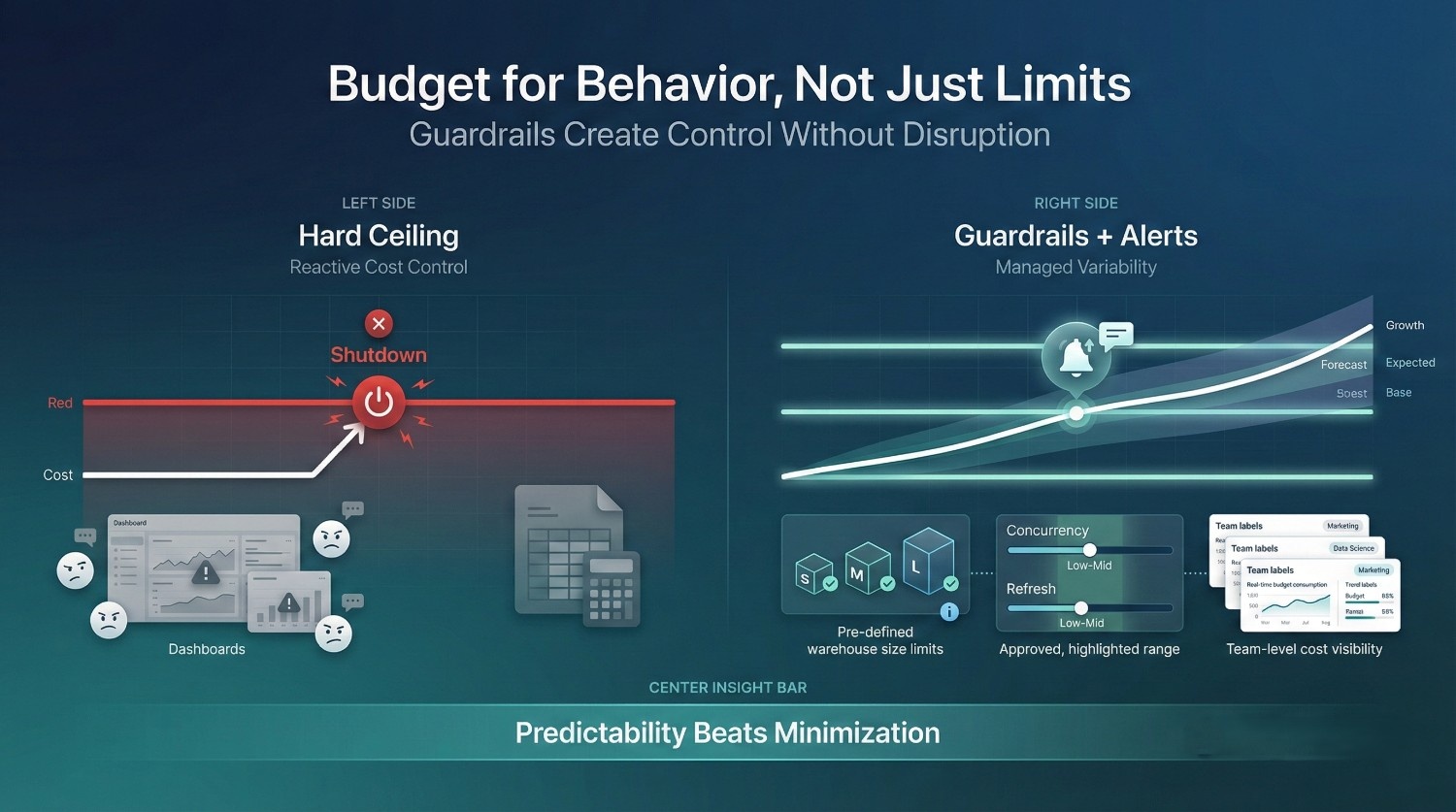

Guardrails Instead of Ceilings

Guardrails define acceptable behavior without stopping work.

Examples:

- Maximum warehouse sizes by workload type

- Restrictions on production warehouses for ad-hoc analysis

- Time-bound limits for large backfills and reprocessing

These controls shape usage patterns without surprising users. Predictable constraints tend to influence behavior more effectively than sudden enforcement actions.

Threshold Alerts, Not Shutdowns

Alerts preserve visibility without disruption. Effective alerts:

- Notify when spend deviates from forecast

- Trigger investigation, not enforcement

- Include context: which warehouse, which workload, which team

This allows finance and engineering to respond together, before panic sets in. Early visibility supports investigation and learning rather than reactive cost cutting.

Scenario-Based Forecasting

Budgets work best when they acknowledge uncertainty. Instead of one number:

- Base case: expected steady-state usage

- Growth case: increased adoption and self-service

- High-usage case: migration, backfills, or experimentation

Finance gains confidence not from precision, but from bounded outcomes. Scenario ranges allow leadership to plan responses instead of reacting to surprises.

Why Predictability Beats Minimization

CFOs do not need Snowflake to be cheap. They need it to be predictable and defensible. Predictability enables planning, while minimization without context often signals underutilization.

Predictable spend:

- Enables better planning

- Reduces invoice shock

- Supports strategic adoption

Minimized spend:

- Often signals underuse

- Masks deeper organizational issues

- Creates fragility

The CFO-Level Insight

Snowflake budgeting works when it treats cost as a managed operating variable, not a fixed line item. Guardrails guide behavior. Alerts create awareness. Forecasts provide confidence. That combination delivers control, without sacrificing the very value Snowflake was adopted to create.

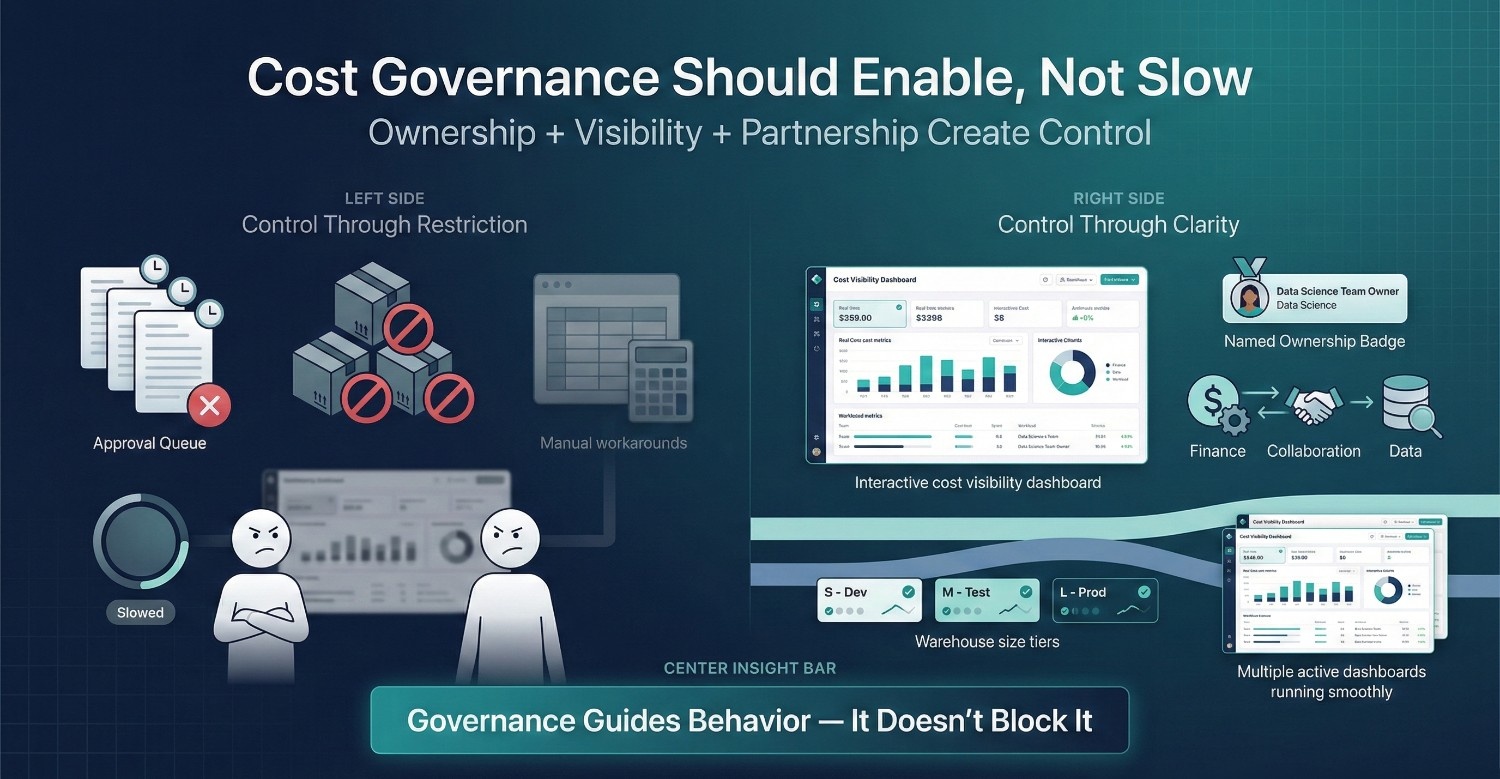

Cost Governance Without Slowing the Business

For many organizations, the word governance triggers concern because it is associated with control rather than enablement. It is commonly associated with:

- Delays

- Approval queues

- Reduced autonomy

But Snowflake cost governance does not have to slow the business when it is designed around usage patterns rather than approvals. Done correctly, it does the opposite, it reduces friction by making expectations clear.

Clear Ownership of Snowflake Cost

In practice, high-performing organizations treat Snowflake cost ownership the same way they treat reliability or security ownership: cross-functional, explicit, and reviewable. Cost without ownership always drifts over time. Effective governance starts by answering one simple question:

“Who is accountable for Snowflake spend and usage decisions?”

Not who pays the invoice, but who:

- Decides how warehouses are used

- Approves new workloads

- Arbitrates tradeoffs when cost and performance conflict

Without named ownership:

- Engineers optimize blindly

- Analysts over-consume unknowingly

- Finance reacts after the fact

Ownership turns cost from a surprise into a managed decision.

Cost Visibility by Team or Workload

Industry case studies from large Snowflake customers show that even rough cost attribution by domain or workload often reduces waste faster than hard technical controls. People reliably change behavior when they can see the impact of their decisions.

Snowflake cost becomes governable when:

- Spend is attributed to teams, domains, or workloads

- Dashboards show trends, not just totals

- Usage patterns are visible alongside outcomes

This does not require perfect allocation.

Even directional visibility is enough to:

- Reduce waste

- Encourage reuse

- Create peer accountability

Opaque costs create fear. Visible costs create discipline and shared accountability.

Finance + Data Partnership Models

Snowflake cost governance consistently fails when finance and data operate in isolation. Strong models usually look like:

- Finance defines acceptable risk and budget ranges

- Data teams explain usage patterns and tradeoffs

- Both review trends regularly, not only during overruns

This shifts the dynamic:

- From enforcement to collaboration

- From blame to understanding

- From reactive cuts to proactive shaping

Finance does not need to become technical. Data teams do not need to become accountants. They just need a shared operating model for cost, usage, and tradeoffs.

Why Governance Should Guide Behavior, Not Punish It

Punitive governance reliably produces predictable results:

- Workarounds

- Shadow systems

- Distrust

Behavioral governance works because it:

- Makes tradeoffs explicit

- Sets norms before problems appear

- Preserves autonomy within clear boundaries

The goal is not to stop usage or experimentation. It is to ensure usage is intentional, visible, and aligned with value. Governance succeeds when it shapes daily behavior, not when it reacts to monthly invoices.

The CFO-Level Insight

Snowflake cost governance succeeds when:

- Ownership is explicit

- Costs are visible where decisions are made

- Finance and data share responsibility

When governance guides behavior instead of punishing outcomes, Snowflake remains fast, flexible, and financially controlled, without becoming another bottleneck.

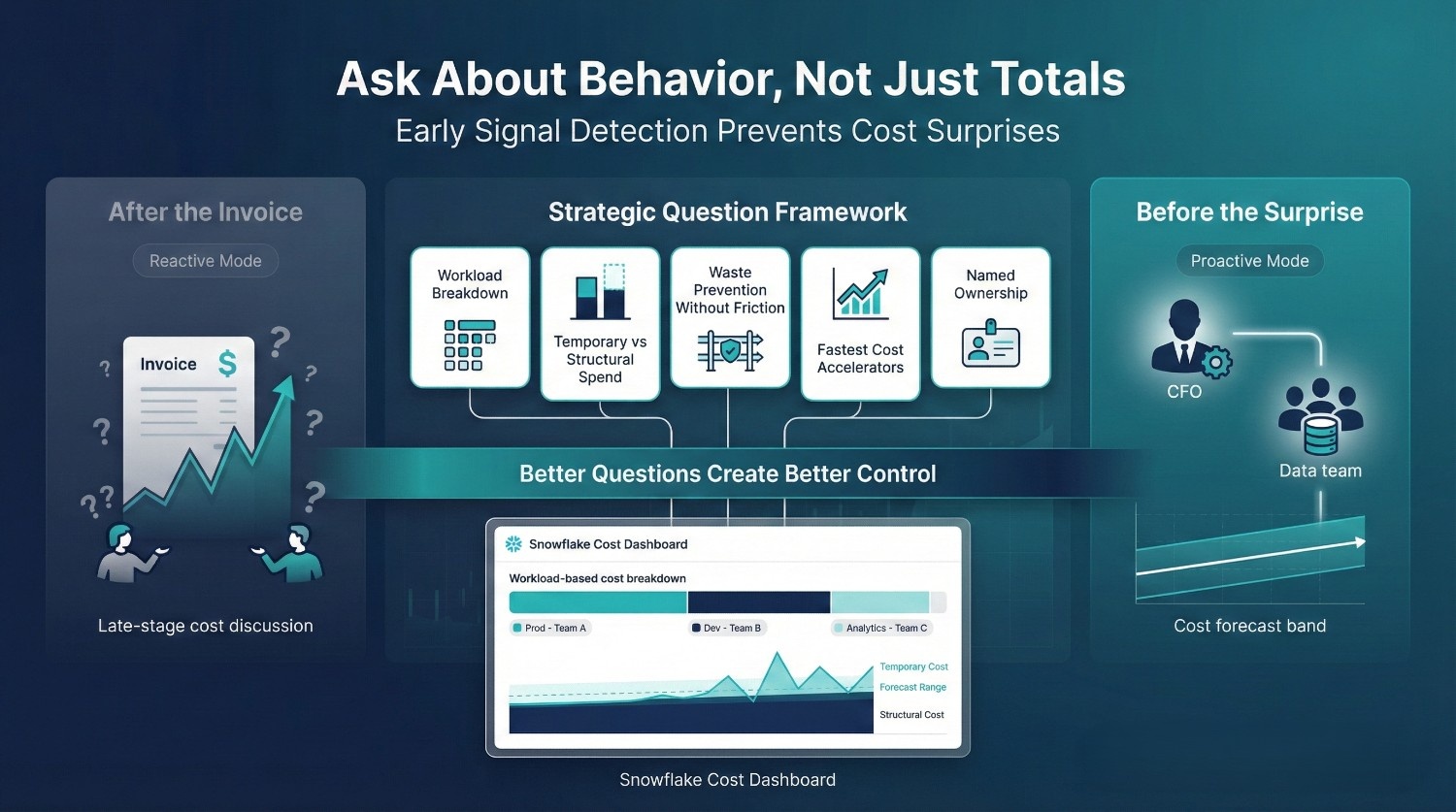

Questions CFOs Should Ask Their Data Teams

CFOs do not need to understand Snowflake internals to govern Snowflake cost well. They need to ask the right questions that reveal behavior, risk, and control gaps before invoices become a problem. The goal of these questions is not interrogation. It is early signal detection.

“Which workloads drive most of our Snowflake cost?”

This question forces clarity on where Snowflake spends actually originates. A good answer should:

- Break cost down by workload (ELT, BI, ad-hoc, data science, validation, exports)

- Identify the top few cost drivers, not just totals

- Explain whether those workloads are expensive because of frequency, concurrency, or warehouse sizing

If the team cannot answer this clearly, the cost is already unmanaged, even if it is still low. In mature organizations, this breakdown is reviewed regularly and tied to workload owners rather than treated as a one-time analysis.

“Which costs are temporary vs. structural?”

Not all Snowflake spend should be treated equally. This question distinguishes between:

- Temporary costs: migrations, backfills, reconciliation, experimentation

- Structural costs: recurring dashboards, core reporting, steady-state analytics

Without this distinction:

- One-time spikes get mistaken for permanent trends

- Finance reacts too aggressively

- Teams lose confidence in the platform

Healthy organizations can point to which costs will naturally decay, and what won’t.

“How do we prevent waste without blocking analytics?”

This question surfaces the organization’s governance philosophy in practice. Strong answers reference:

- Guardrails instead of hard limits

- Workload isolation

- Visibility and feedback loops

Weak answers tend to default to:

- Slowing queries

- Cutting access

- Blanket restrictions

If waste prevention relies on blocking usage, adoption and trust typically suffer next.

“What behaviors would increase the spend the fastest?”

This is one of the most revealing questions. It forces teams to think in behavioral terms, not technical ones. Good answers might include:

- Uncontrolled ad-hoc querying on production warehouses

- Duplicate dashboards recomputing the same logic

- Aggressive refresh schedules

- Migration validation running longer than planned

If the team cannot articulate these risks, cost surprises are inevitable.

“Who owns Snowflake cost decisions day to day?”

This question cuts through organizational ambiguity. You’re looking for:

- A named owner or small ownership group

- Clear decision rights

- A process for tradeoffs

If ownership is “shared” or unclear, cost control will be reactive by default.

Why These Questions Matter

These questions:

- Expose blind spots early

- Shift conversations from invoices to intent

- Create shared language between finance and data

Asking these questions early shifts Snowflake cost conversations from reactive explanation to intentional design. Most Snowflake cost problems do not begin with overspending. They begin with unasked governance questions.

For CFOs, asking these early is the difference between:

- Governing cost proactively

- Or explaining surprises after the fact

That’s where real control starts.

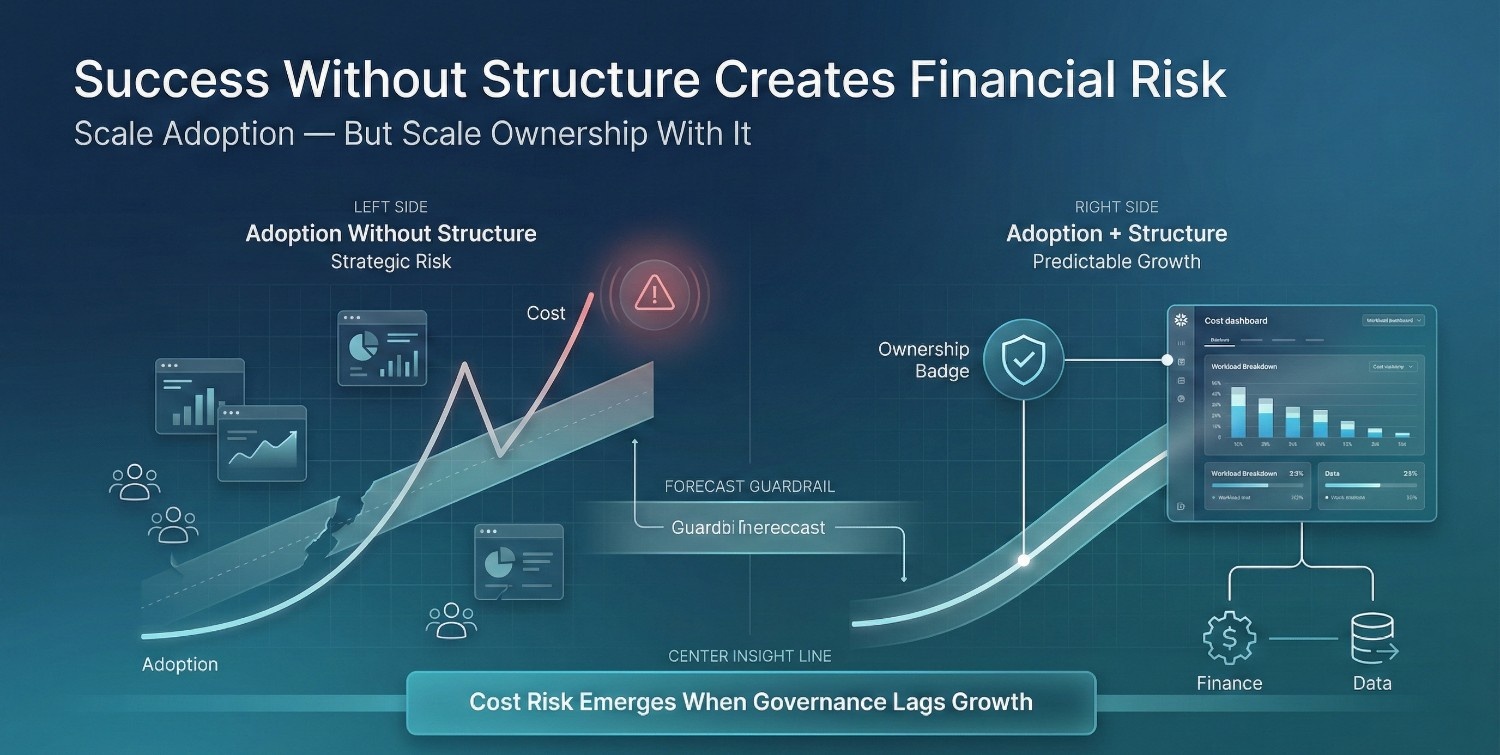

When Snowflake Cost Becomes a Strategic Risk

Snowflake cost becomes a strategic risk not when something is broken, but when the organization is scaling successfully without enough structure. This is the paradox CFOs often encounter:

The platform is working. Adoption is growing. And cost suddenly feels dangerous.

That’s not a coincidence. It is a signal.

Rapid Company Growth

Growth often increases Snowflake usage faster than finance models expect. As companies scale:

- More teams rely on data for decisions

- More dashboards are created

- More ad-hoc analysis becomes business-critical

In practice, Snowflake cost growth during rapid scaling is frequently correlated with increased decision velocity, not inefficiency. The risk emerges only when cost ownership does not scale alongside usage. Snowflake is designed to remove friction from this growth.

Without guardrails, spend scales just as freely.

What makes this risky is not the growth itself, but the absence of proportional cost discipline and ownership as usage expands.

Decentralized Analytics

Decentralization increases speed, but also fragmentation. When teams operate independently:

- Each builds their own dashboards

- Similar logic is recomputed repeatedly

- Shared definitions erode

From a cost perspective:

- Spend rises without clear ownership

- Reuse drops

- Predictability disappears

Decentralization without coordination turns Snowflake into a shared resource with unclear stewardship and accountability.

Migrations in Flight

Active migrations are one of the most underestimated cost risk periods. During migration:

- Legacy systems and Snowflake run in parallel

- Validation queries multiply

- Backfills and reprocessing spike compute usage

These costs are expected, but often unplanned. When migration cost is not framed as:

- Temporary

- Intentional

- Time-boxed

Finance interprets it as uncontrolled spend when migration costs are not clearly labeled as temporary and value-creating.

Poor Ownership Clarity

This is the most dangerous condition of all. When no one owns:

- Cost decisions

- Warehouse strategy

- Tradeoffs between speed and spend

Then:

- Everyone optimizes locally

- No one optimizes globally

- Finance intervenes too late

Snowflake cost becomes risky not because it is high, but because no one can explain it confidently.

Why Cost Risk Increases With Success, Not Failure

Snowflake cost risk grows when:

- Adoption accelerates

- Data becomes central to decisions

- Teams rely on analytics instead of intuition

In other words, when Snowflake is doing its job. For CFOs, this reframes the problem. The question is not:

“How do we stop this spending?”

It is:

“Do we have the ownership, visibility, and decision discipline to scale usage safely?”

Snowflake cost becomes a strategic risk only when adoption and success outpace governance, ownership, and cost visibility. In other words, Snowflake cost risk is a lagging indicator of organizational design gaps, not a leading indicator of platform misuse.When structure grows with adoption, cost remains predictable, and Snowflake remains a strategic asset, not a liability.

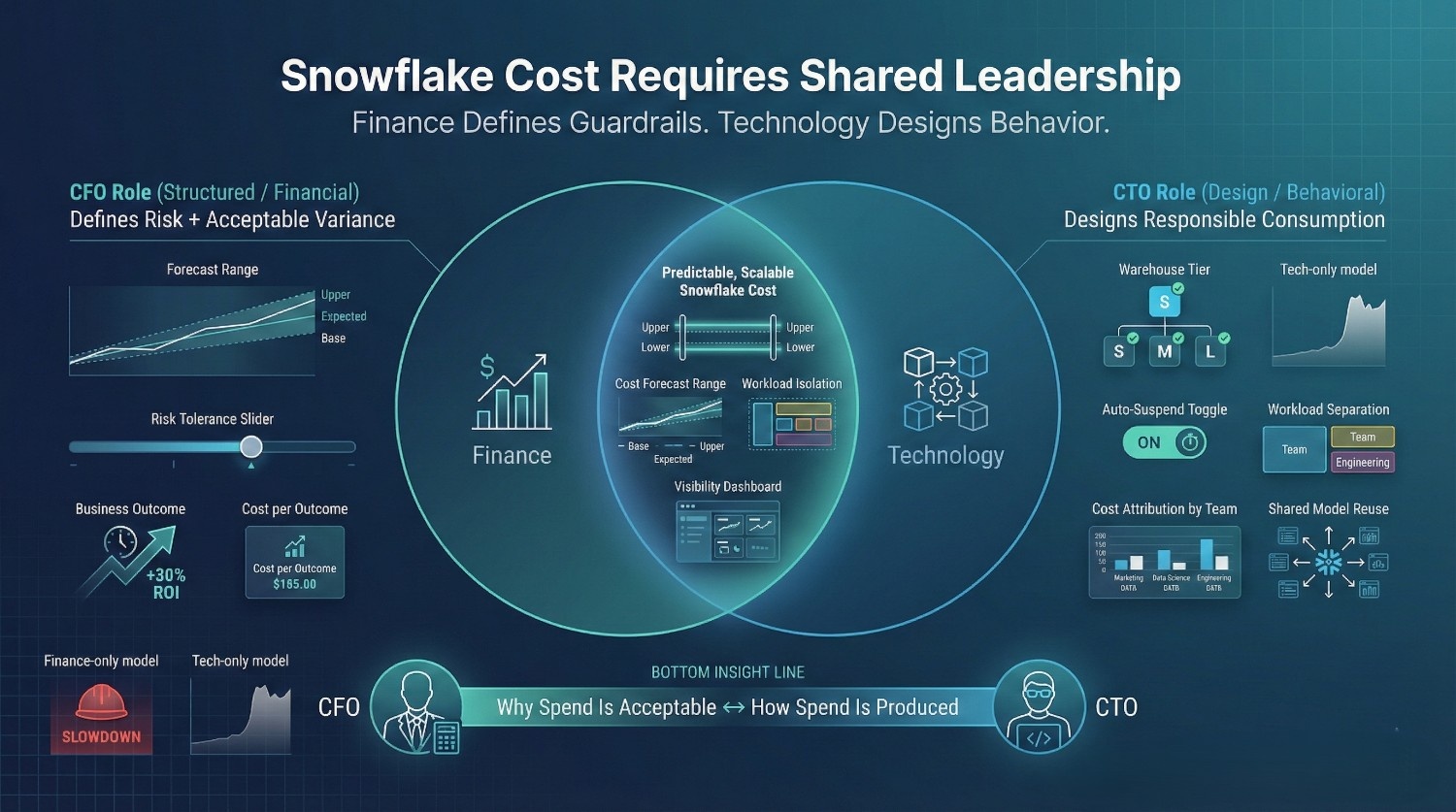

How CFOs and CTOs Should Share Ownership of Snowflake Cost

Snowflake cost governance fails most often for one simple reason:

It is owned by only one side of the organization.

When finance owns it alone, cost control becomes blunt and reactive. When technology owns it alone, spending becomes opaque and hard to defend. Snowflake cost sits at the intersection of economics and system design, which requires shared and explicit ownership

The CFO’s Role: Demand Predictability, Not Just Reduction

CFOs add the most value when they focus on predictability, not minimization. Effective CFO ownership looks like:

- Demanding forecast ranges, not single-point estimates

- Asking which costs are structural vs temporary

- Expecting explanations tied to business activity, not technical detail

- Framing Snowflake cost as an operating expense tied to outcomes

CFOs should not be deciding warehouse sizes or query patterns directly. They should be deciding acceptable risk, variance, and return. When finance pushes only for lower spend:

- Usage is driven underground

- Value creation slows

- Trust between teams erodes

Predictability creates confidence. Confidence enables growth. Finance teams that succeed with Snowflake typically focus on bounding outcomes and variance rather than enforcing fixed limits, allowing usage to scale while remaining explainable.

The CTO’s Role: Design for Responsible Consumption

CTOs are uniquely positioned to shape Snowflake cost before it appears on an invoice. That responsibility includes:

- Designing workload isolation so costs are attributable

- Setting sensible defaults (warehouse sizes, auto-suspend, access patterns)

- Making usage visible without shaming

- Ensuring teams understand the cost implications of their choices

CTOs do not need to optimize for the lowest bill.

They need to optimize for clarity, reuse, and disciplined scale. When systems are designed without cost transparency:

- Finance loses trust

- Governance arrives too late

- Engineering credibility suffers

Good system design is cost governance in disguise.

Where Shared Ownership Actually Happens

Shared ownership does not mean shared confusion. It means:

- CFOs define financial guardrails and tolerance

- CTOs translate those guardrails into technical behavior

- Both review trends together, regularly, not only during overruns

The handoff should be explicit:

- Finance owns why spend is acceptable

- Technology owns how spend is produced

Anything else creates gaps.

Why Single-Owner Models Consistently Break Down

When CFOs own Snowflake cost alone:

- Controls become restrictive

- Analytics slows

- Workarounds emerge

When CTOs own it alone:

- Cost explanations become technical

- Finance feels blindsided

- Trust erodes at the leadership level

Snowflake cost is neither purely financial nor purely technical. It is largely behavioral. And behavioral problems require joint accountability. Shared ownership works best when disagreements about cost and performance are resolved explicitly, not deferred or escalated only after invoices arrive.

The Core Insight

Snowflake cost governance works when:

- CFOs insist on predictability and value framing

- CTOs design systems that make behavior visible and intentional

- Neither side abdicates responsibility to the other

When CFOs and CTOs share ownership, Snowflake cost becomes:

- Explainable

- Defensible

- Scalable

Not a recurring surprise, and not a structural constraint on growth.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Because Snowflake pricing is usage-based, not capacity-based. There are no fixed licenses or reserved limits by default. Cost changes as behavior changes, more users, more queries, more experimentation, often without a clear “purchase event” that finance is used to tracking.

No. Snowflake is often cost-efficient at small and medium scale. Cost issues usually emerge when adoption grows faster than governance. High spend typically reflects how widely and freely data is used, not inefficient technology.

Because cost is driven more by:

- Query frequency

- Concurrency

- Validation and reprocessing activity

- New users and dashboards

Doubling usage behavior can increase cost even if data size stays flat.

No. CFOs should aim to make Snowflake cost predictable and defensible, not minimal. Very low cost can signal underutilization, slow decisions, or lack of trust in data, which is a business risk, not a win.

- Temporary costs come from migrations, backfills, validation, and experimentation. They should decay over time.

- Structural costs come from recurring dashboards, core reporting, and steady-state analytics.

If teams cannot explain which is which, finance will assume everything is permanent.

Hard caps:

- Interrupt analysis mid-work

- Slow dashboards

- Push teams toward shadow tools

They reduce Snowflake spend on paper but increase real organizational cost through lost productivity and trust.

Better approaches include:

- Scenario-based forecasts (base, growth, high-usage cases)

- Guardrails on behavior, not shutdowns

- Threshold alerts with context

- Regular finance + data reviews

Predictability is more valuable than strict ceilings.

By insisting on:

- Clear ownership of Snowflake spend

- Visibility by team or workload

- Agreed guardrails on usage

- Shared accountability with technology leadership

Governance should guide behavior, not punish outcomes.

Ownership must be shared:

- CFOs own acceptable variance, predictability, and value framing

- CTOs own system design, defaults, and transparency

When only one side owns cost, governance fails.

Snowflake cost becomes risky during success, not failure, especially when:

- The company is growing fast

- Analytics is decentralized

- A migration is in progress

- Cost ownership is unclear

Risk appears when adoption outpaces structure.

Key questions include:

- Which workloads drive most of our spend?

- Which costs are temporary vs structural?

- What behaviors would spike cost fastest?

- Who decides tradeoffs between speed and spend?

These questions surface control gaps early, before invoices force reactive decisions.

Stop treating Snowflake as a fixed IT expense. Snowflake cost is usage economics. When finance focuses on behavior, value, and predictability, not just totals, Snowflake becomes a scalable asset instead of a recurring surprise.