Table of Contents

Introduction

There is a comforting myth that quietly governs how many organizations approach cloud data migration:

“If we hire strong engineers, the migration will succeed.”

It sounds reasonable. Data migrations involve pipelines, schemas, transformations, infrastructure, and performance tuning—surely this is an engineering problem. So companies assemble smart teams, bring in experienced data engineers, and expect the rest to fall into place.

And yet, when cloud data migration efforts fail, they often involve excellent engineers — which raises the question of when organizations actually need data migration consulting.

Not junior teams.

Not careless implementations.

Not a lack of technical competence.

In fact, some of the most expensive and disruptive migration failures happen inside organizations with highly capable engineers, modern tooling, and well-funded initiatives.

This contradiction is the first signal that something deeper is going on.

The Real Nature of Cloud Data Migration

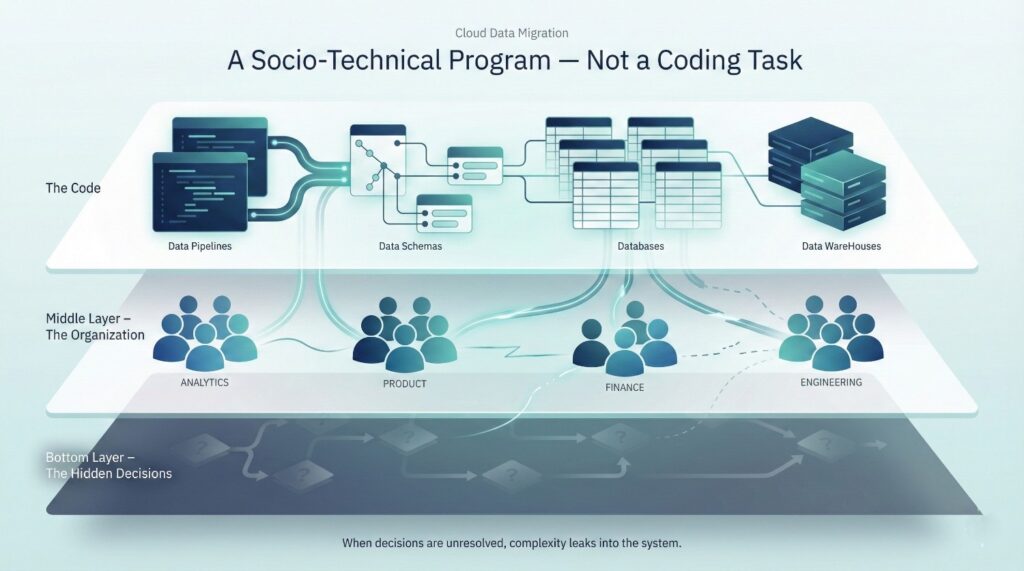

A cloud data migration is rarely just a technical exercise. It is a socio-technical program—a coordinated change across systems, teams, incentives, workflows, and decision-making structures.

Code is only one layer.

Beneath it sit questions that engineering skill alone cannot answer:

- Who owns data definitions when multiple teams depend on them?

- Who approves schema changes that break downstream dashboards?

- How are business stakeholders kept confident while systems are duplicated?

- What happens when results are correct technically, but differ from legacy outputs or are trusted operationally?

- Who decides when “good enough” is good enough to cut over?

When these questions are left unresolved, engineers end up absorbing organizational ambiguity into technical complexity. Pipelines become defensive. Logic becomes duplicated. Temporary workarounds become permanent architecture. And the migration quietly drifts off course—sometimes for months—before anyone realizes it has failed.

Why Failures Rarely Look Like Failures at First

One of the most dangerous aspects of cloud data migration is that failure is often hard to detect in the early stages.

Jobs run.

Dashboards load.

Numbers appear reasonable.

From the outside, progress seems steady. Internally, however, warning signs accumulate:

- Parallel systems produce slightly different results

- Engineers spend more time reconciling data than building new capabilities

- Business users begin asking which dashboard is “the real one”

- Costs increase without a corresponding increase in confidence

- Cutover dates quietly move from “planned” to “tentative”

None of this looks like a broken pipeline. It looks like a migration that is “almost there.”

By the time leadership recognizes the problem, the organization is often deeply invested—financially and politically—making a clean reset materially harder.

Where Migration Failures Actually Come From

Contrary to popular belief, most cloud data migration failures are not caused by:

- Poor SQL

- Inefficient transformations

- Inadequate cloud infrastructure

- The wrong data warehouse choice

Those issues are usually solvable.

The dominant failure modes usually originate elsewhere:

- Structural gaps where ownership is unclear and decisions stall

- Incentive mismatches where teams are rewarded for local success, not global correctness

- Visibility failures where progress is measured in tasks completed rather than trust gained

- Leadership blind spots where risk is assumed to be technical instead of organizational

Engineers end up compensating for these gaps with complexity, manual checks, and duplicated logic—until the system becomes fragile, slow, and untrustworthy.

What This Article Is (and Is Not)

This is not another checklist of tools, frameworks, or “best practices.”

You will not find generic advice like:

- “Communicate more”

- “Do better testing”

- “Choose the right cloud provider”

Instead, this article is a failure analysis.

We will examine why cloud data migration initiatives break down even when the technical talent is strong, by exploring four categories of failure:

- Technical traps that emerge from defensive engineering and hidden assumptions

- Organizational bottlenecks that stall progress and distort design decisions

- Leadership blind spots that underestimate risk and overestimate readiness

- Measurement and accountability gaps that make success impossible to define

Understanding these failure patterns is the first step toward designing migrations that are not just technically correct—but operationally trusted, politically survivable, and measurably successful.

In the sections that follow, we will dissect each category in depth and show how cloud data migration fails not because engineers aren’t good enough—but because the system around them isn’t designed to let them succeed.

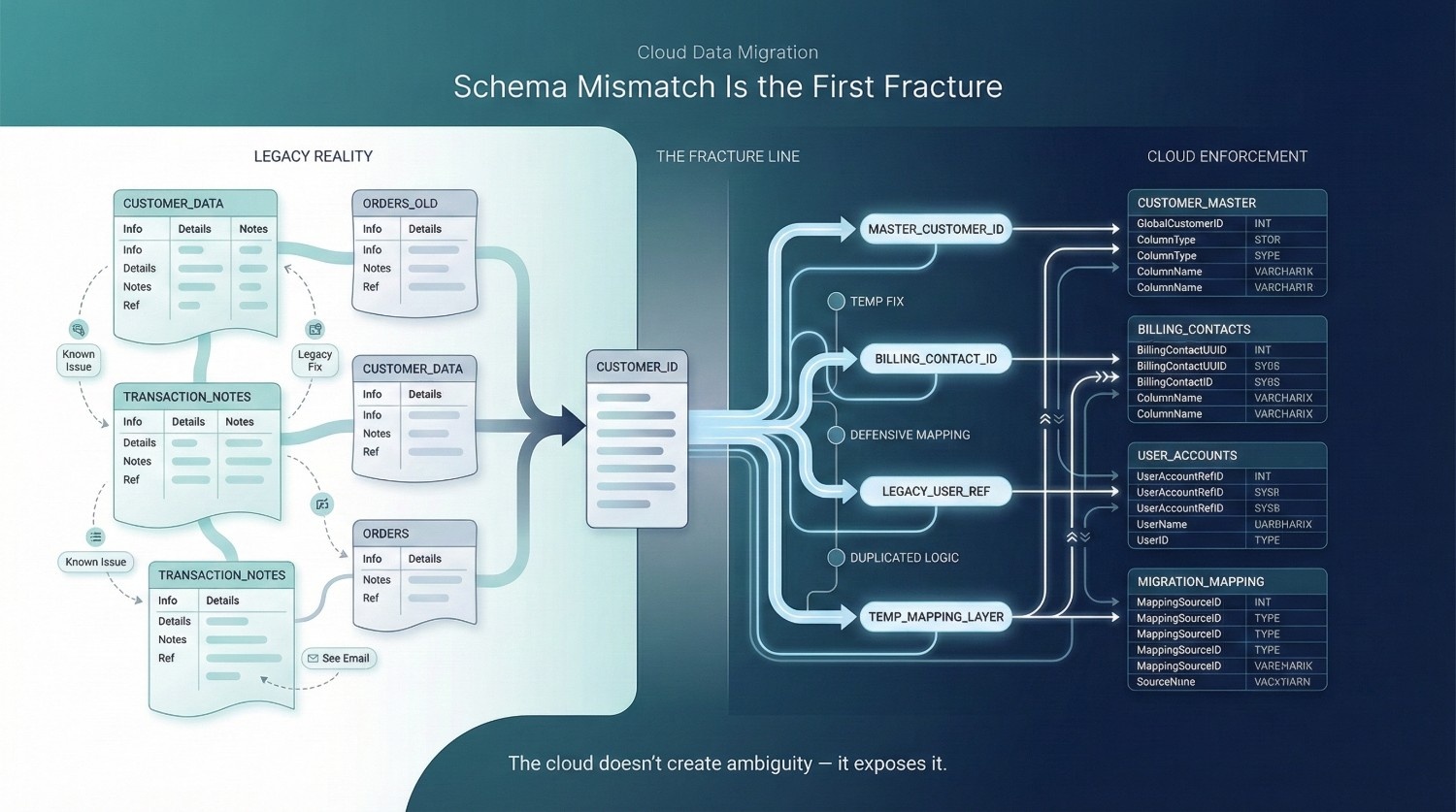

Schema Mismatch

Schema issues are often described as a “data cleanup problem,” something to be handled once the migration is underway. In reality, schema mismatch is usually the first major fracture in a cloud data migration—because it exposes decisions that were never formally made in the first place.

What looks like a technical inconsistency is often a historical record of organizational ambiguity.

Legacy Schemas Were Never Designed to Move

Most legacy schemas were not built with portability, scale, or analytical correctness in mind. They evolved to serve immediate operational needs, not long-term data platforms.

Common optimization targets included:

- OLTP efficiency

Tables designed for fast writes, minimal joins, and transactional integrity—often at the expense of clarity or normalization. - Manual reporting workflows

Columns added to satisfy a single Excel report, finance extract, or ad-hoc SQL query, without concern for reuse or semantics. - Tool-specific quirks

Fields shaped around the limitations of a specific BI tool, CRM export, or reporting engine—sometimes encoding logic directly into column names or values.

These schemas worked because the surrounding context compensated for their flaws. Analysts knew which filters to apply. Finance teams knew which rows to exclude. Engineers understood which fields were “real” and which were “legacy.”

A cloud data migration removes that protective context.

Modern Cloud platforms enforce stricter type safety and explicit schema definitions, though they vary widely in rigidity (Snowflake’s VARIANT types vs. BigQuery’s strict schemas). What used to be implicit knowledge suddenly becomes required structure. Hidden assumptions surface—not because the cloud is rigid, but because it is honest.

The migration rarely introduces schema problems. It primarily reveals them.

One Source, Many Meanings

A particularly dangerous pattern emerges when a single column carries multiple meanings across teams.

The same field name appears everywhere, but its interpretation changes depending on who is using it.

Common examples include columns like:

- status

- type

- flag

- category

- source

To one team, status = active might mean “billable.” To another, it means “not deleted.”

To a third, it means “visible in the UI.”

All of these interpretations may be correct—locally.

The problem arises when a cloud data migration attempts to unify data across domains. Suddenly, a single column is expected to support multiple downstream use cases, analytics models, and business decisions. The ambiguity that was once manageable becomes toxic.

Engineers are often asked to “standardize” these fields. But standardization requires choosing one meaning over another—or creating multiple new definitions. That is not a technical task. It is a semantic decision with real business consequences.

Without explicit ownership, these decisions get deferred. The schema moves forward unchanged, and the ambiguity is preserved—now amplified across a larger platform.

Schema Drift During Migration

Even if schemas are documented at the start of a migration, they often do not remain stable.

Upstream systems continue to evolve:

- New fields are added

- Existing fields change meaning

- Data types shift subtly

- Nullability changes without notice

In many organizations, no single person owns the schema as a contract. Changes are made to “unblock” a feature or fix an operational issue, with little visibility into downstream impact.

During a cloud data migration, this creates a dangerous lag effect.

The pipeline still runs.

The data still loads.

The breakage does not appear immediately.

Weeks later, a dashboard shows an unexplained shift. A metric no longer reconciles. Finance questions historical comparisons. Engineering teams scramble to trace the issue back through layers of transformation logic—only to discover that the source changed quietly during the migration window.

By then, the damage is already done. Trust erodes, and the migration inherits the blame.

Why Engineers Can’t “Just Fix It”

When schema issues surface, the instinctive response is to ask engineers to resolve them.

“Can’t we just rename the column?”

“Can’t we map the values?”

“Can’t we clean this up downstream?”

What this overlooks is that schema ambiguity is rarely solvable in code alone.

Choosing whether a column represents lifecycle state, billing eligibility, or UI visibility requires business context. Deciding whether historical data should be reinterpreted or preserved requires stakeholder alignment. Determining which definition becomes canonical is an organizational decision, not an engineering one.

In the absence of clear ownership, engineers become accidental data arbitrators. They make judgment calls simply to keep the migration moving. Those decisions are rarely documented, rarely validated, and often disputed later—after dashboards are live and stakeholders are watching.

This is how technically correct migrations fail operationally.

Not because the engineers made poor choices—but because they were forced to make choices that were never theirs to make.

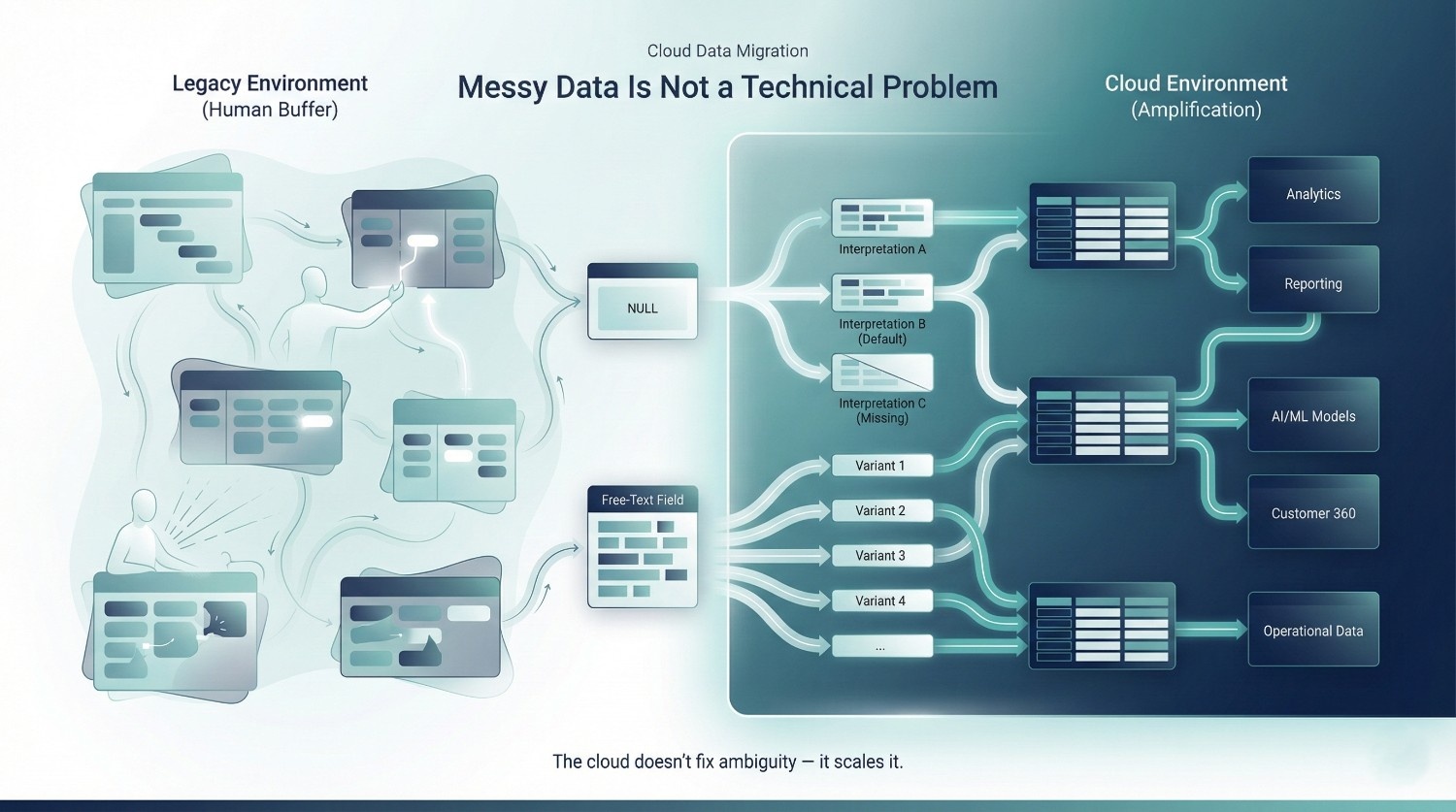

Messy Data Is Not a Technical Problem

When cloud data migration projects start to wobble, “data quality” is often blamed as an unfortunate technical reality—something inherited from the past and best handled with more transformations, more validation rules, or more downstream fixes.

This framing is comfortable. It suggests that messy data is simply the cost of legacy systems.

In practice, messy data is rarely accidental. It is a record of decisions deferred, exceptions tolerated, and accountability avoided. A cloud data migration does not create these issues—it strips away the layers that once concealed them, forcing leaders to confront how CTOs should think about migration risk.

Inconsistent Historical Data

Legacy datasets often contain inconsistencies. The problem is not their existence, but how casually they are rationalized.

Common patterns include:

- Nulls that mean different things

A missing value might indicate “unknown,” “not applicable,” “not yet entered,” or “intentionally blank.” These distinctions often exist only in tribal knowledge, not in documentation or code. - Free-text fields carrying structured meaning

Important attributes—statuses, categories, reasons, overrides—are stored as loosely formatted text. Over time, spelling variations, abbreviations, and internal shorthand accumulate. What should have been a controlled enum becomes an unbounded taxonomy. - “We’ll clean it later” debt

Temporary shortcuts become permanent. A one-off import bypasses validation. A new field launches without constraints. Each decision seems small, but collectively they hard-code ambiguity into the data layer.

In many legacy environments, these issues are survivable. Queries are slow, usage is limited, and analysts learn which filters “usually work.” The system functions not because the data is clean, but because people compensate for it.

A cloud data migration significantly reduces that human buffer.

Cloud Doesn’t Clean Data — It Amplifies It

One of the most common misconceptions about cloud platforms is the belief that better infrastructure somehow improves data quality.

It does not.

Cloud systems are faster, more scalable, and more interconnected. Those qualities magnify whatever already exists.

- Faster queries surface inconsistencies immediately.

Aggregations that once took hours now run in seconds—and reveal contradictions that were previously invisible or ignored. - Reusable models spread bad assumptions further.

A flawed transformation becomes a shared dependency, propagating errors across dashboards, reports, and downstream systems. - Machine learning models often surface data quality issues faster than dashboards. While humans can rationalize anomalies, models may fail, degrade silently, or learn incorrect patterns from inconsistent data. Inconsistent labels, leaky features, and noisy inputs break ML pipelines long before business users notice issues in BI tools.

What looked like “acceptable messiness” in a legacy stack becomes operational risk in a cloud environment. The platform does not resolve ambiguity—it scales it.

Why Migrations Expose Data Truths Leadership Avoided

Data quality is often treated as a technical hygiene issue, but it is more accurately a reflection of organizational behavior.

Inconsistent data usually indicates:

- Undefined ownership over critical fields

- Incentives that prioritize speed over correctness

- Tolerance for exceptions without governance

- A culture where “fix it in reporting” is acceptable

Legacy systems allow these behaviors to persist quietly. Manual processes, slow feedback loops, and siloed usage make it easy to avoid hard conversations.

A cloud data migration removes those hiding places.

When data becomes centralized, visible, and reusable, inconsistencies can no longer be localized. Questions that were once deferred become unavoidable:

- Which definition is correct?

- Which historical values are wrong?

- Who is accountable for fixing them?

- How much inconsistency is acceptable going forward?

These are not engineering questions alone. They are leadership decisions.

When leadership avoids answering them, engineers are forced to encode uncertainty into pipelines. The migration moves forward, but trust erodes. Stakeholders begin to question numbers. Teams hesitate to rely on the new platform. The migration is labeled “technically successful” but practically unusable.

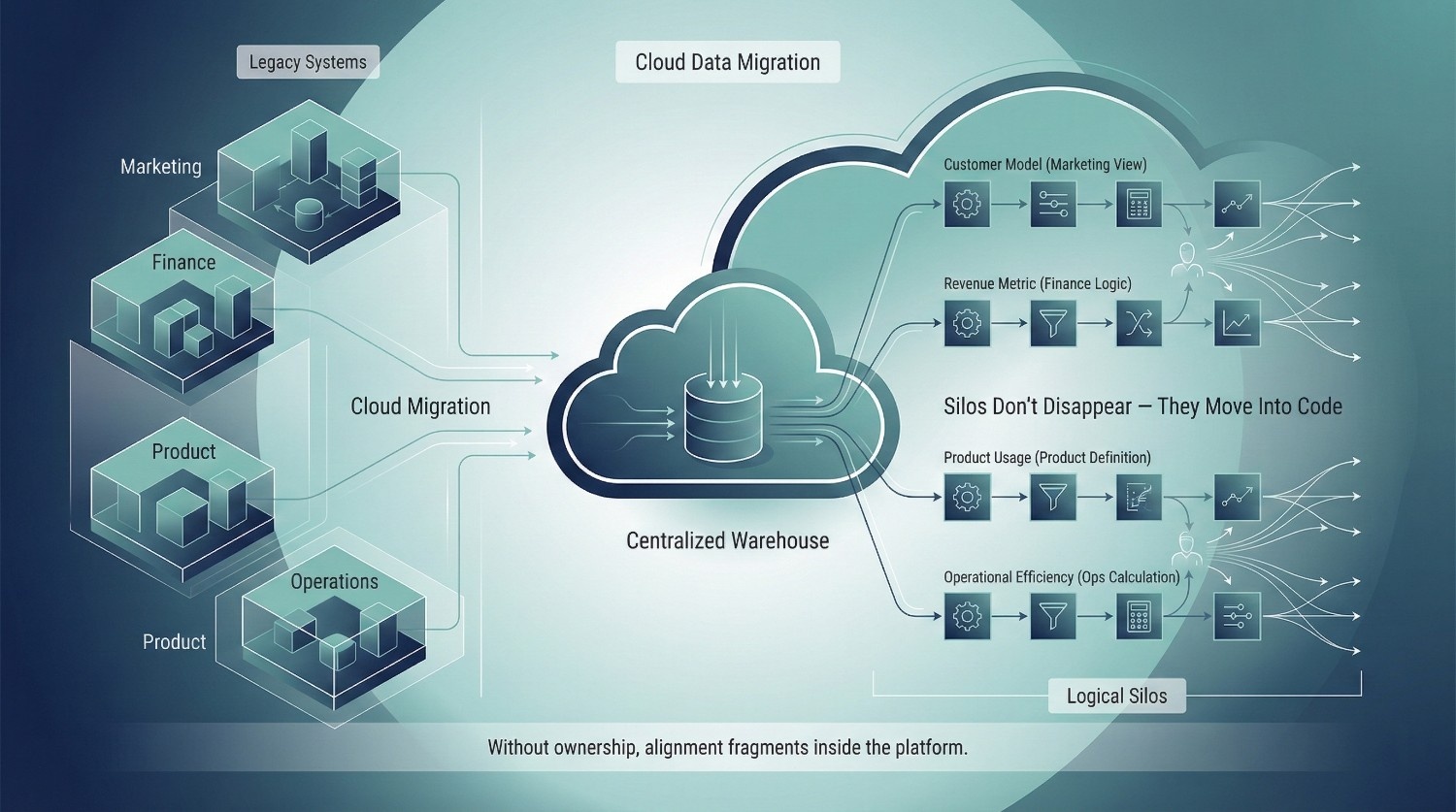

Data Silos Don’t Disappear — They Often Multiply

One of the most persistent assumptions in cloud data migration is that moving data into a modern warehouse automatically dissolves silos. Centralize everything in one place, and alignment will follow.

It rarely does.

What actually happens is more subtle—and potentially more dangerous. Silos don’t necessarily disappear. They often reproduce at a higher level, now embedded in pipelines, models, and definitions that look unified but behave independently.

The Illusion of Centralization

Migrating data into a single platform like Snowflake or BigQuery creates a powerful visual signal of consolidation. Everything lives in one system. Tables are accessible. Queries run fast.

But central storage is not the same as unified data.

In many migrations, each team builds pipelines that reflect their own priorities:

- Marketing ingests customer data optimized for attribution

- Finance models revenue for reporting and audits

- Product structures events around feature usage

- Operations tracks fulfillment and lifecycle states

All of this data may sit in the same warehouse, yet remain conceptually siloed. Definitions diverge. Metrics are recalculated differently. Transformations encode local assumptions.

Instead of removing silos, the migration often replicates them in code.

The difference is that now they often look official. Dashboards are polished. Queries are fast. Disagreements are harder to detect—and harder to resolve.

Ownership Gaps

As silos multiply, a more fundamental issue surfaces: ownership.

When definitions conflict, someone has to decide which version is correct. In practice, that decision is often unclear—or actively avoided.

Common questions arise quickly:

- Who owns the definition of a customer?

- Who owns revenue numbers when billing, finance, and sales disagree?

- Who has authority to declare a metric “correct” and enforce it?

In legacy systems, these conflicts were often masked by separation. Each team trusted its own reports. Comparisons were rare and slow.

A cloud data migration collapses that distance. Data is now shared, reused, and exposed to leadership. Conflicting numbers appear side by side.

Without explicit ownership, disagreements often turn into stalemates. Few people want to be accountable for definitions that impact incentives, forecasts, or performance reviews. Decisions stall—not because people disagree, but because no escalation path exists.

The migration continues, but alignment does not.

Engineers Stuck Between Teams

When ownership is unclear, engineers become the default arbiters.

They sit between teams with conflicting definitions, each backed by reasonable arguments and local context. Marketing wants one interpretation. Finance insists on another. Product needs a third.

There is often no formal process to resolve these conflicts. No governing body. No decision-maker empowered to trade off precision, usability, and business impact.

So engineers do what they can:

- Duplicate logic to satisfy multiple stakeholders

- Add conditional transformations to “keep everyone happy”

- Delay decisions to protect timelines

- Implement temporary workarounds that become permanent

This slows everything down.

Migration timelines often slip not because pipelines are complex, but because every schema change risks reopening unresolved debates. Engineers hesitate to refactor. Teams lose confidence. Progress becomes incremental and fragile.

Eventually, the cloud data migration is labeled “delayed due to complexity,” when a primary blocker was organizational indecision.

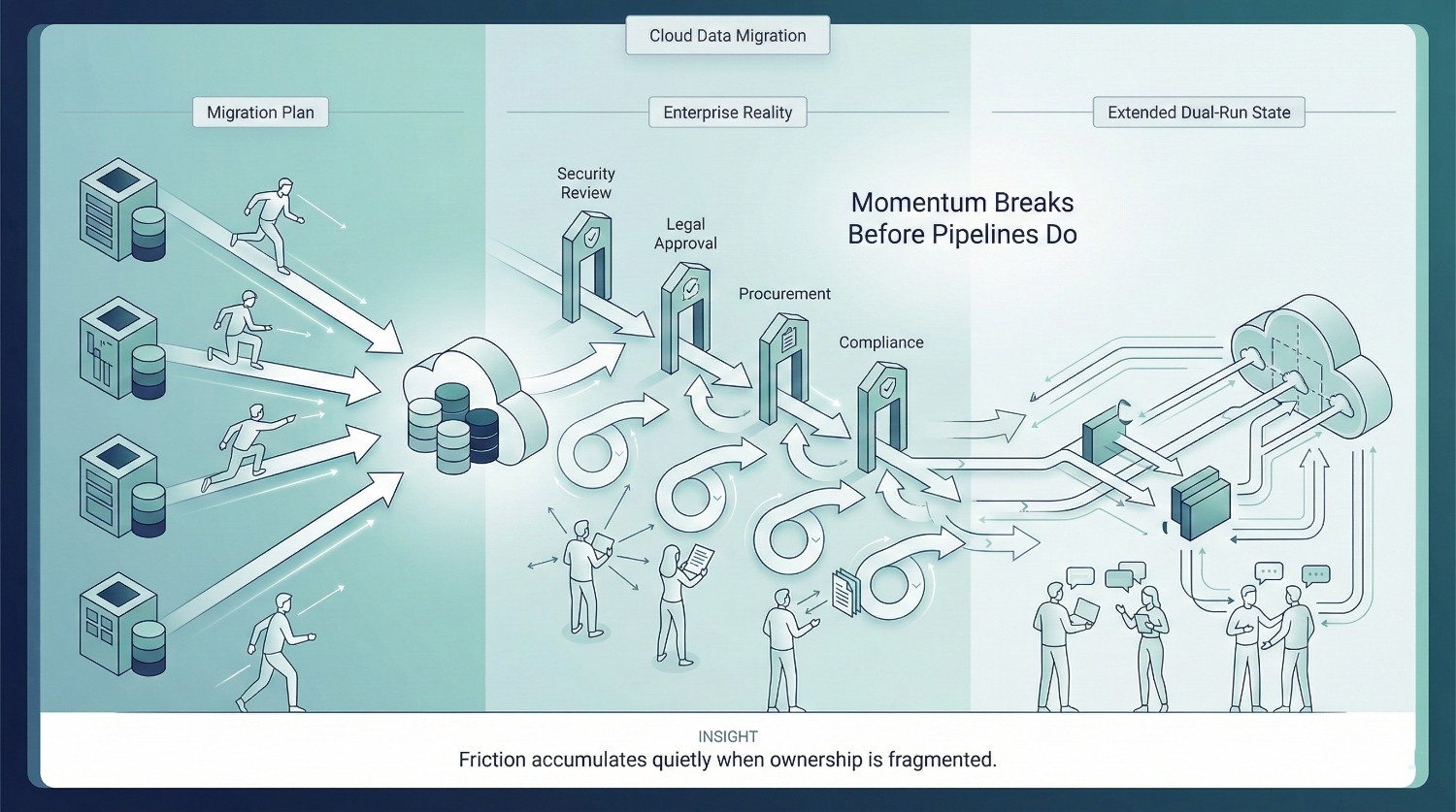

Enterprise Reality

Cloud data migration plans are often built on an implicit assumption: once technical design is complete, execution will be linear. Pipelines will be built, data will move, validation will happen, and the organization will cut over.

Enterprise reality breaks this assumption early.

Not through dramatic failure—but through friction that accumulates slowly and often invisibly.

Migration Velocity vs. Enterprise Governance

Cloud platforms reward speed. Infrastructure can be provisioned in minutes. Pipelines can be iterated daily. Schemas can evolve rapidly—in theory and with sufficient governance alignment.

Enterprises do not operate at that pace.

Every meaningful migration step intersects with governance mechanisms that exist for good reasons, but impose real drag:

- Security reviews

New data locations trigger access reviews, encryption requirements, threat modeling, and audit questions. Each review is reasonable in isolation; collectively, they can introduce weeks of latency. - Legal approvals

Data residency, retention, PII handling, and vendor contracts must be reassessed. Legal teams operate on risk minimization, not migration velocity—and they are rarely resourced for rapid iteration. - Procurement delays

New tools, expanded cloud usage, or consulting support often require procurement cycles that operate on quarterly rhythms, not sprint cycles.

None of this blocks the migration outright. Instead, it creates a stop-start pattern. Engineers build ahead. Then they wait. Then they context-switch. Then they return weeks later to decisions that no longer align cleanly with the original design.

Velocity often collapses—not because work stops, but because continuity breaks.

The Cost of Waiting

Waiting is often not treated as a cost in migration plans. It should be.

When approvals stall and dependencies lag, the impact compounds across teams:

- Engineers context-switch

Migration work competes with feature requests, bug fixes, and operational incidents. Each pause forces engineers to reload mental state, revalidate assumptions, and rediscover decisions that were already made once. - Partial systems live too long

Old and new platforms coexist far beyond their intended overlap. Temporary duplication becomes normal. Reconciliation becomes manual. The longer this phase lasts, the harder it becomes to shut anything down. - Confidence erodes

Stakeholders stop asking when the migration will finish and start asking whether it will ever finish. Trust in timelines weakens. Skepticism grows—not because results are wrong, but because progress feels stalled.

This is one of the primary ways migrations lose political capital.

Nothing is visibly broken. But enthusiasm fades. Support wanes. Teams adapt to the “in-between” state—and the urgency to complete the migration disappears.

Why Migration Timelines Stretch Quietly

Unlike outages or failed launches, cloud data migration delays rarely trigger alarms.

That is often because no single role owns the outcome end-to-end.

- Engineering owns pipelines

- Security owns access

- Legal owns compliance

- Finance owns cost approval

- Business teams own validation

- Leadership owns prioritization—abstractly

But no one owns the full delivery timeline.

Delays are therefore absorbed locally. A review takes longer than expected. A dependency slips a sprint. A decision waits for the next steering meeting. Each delay is rationalized as minor.

Collectively, they can be fatal.

By the time leadership asks why the migration is six months behind schedule, no single decision looks wrong. There is no clear failure point. Just a long trail of reasonable pauses that, together, drained momentum.

This is why cloud data migration timelines stretch quietly—without escalation, without crisis, and without resolution.

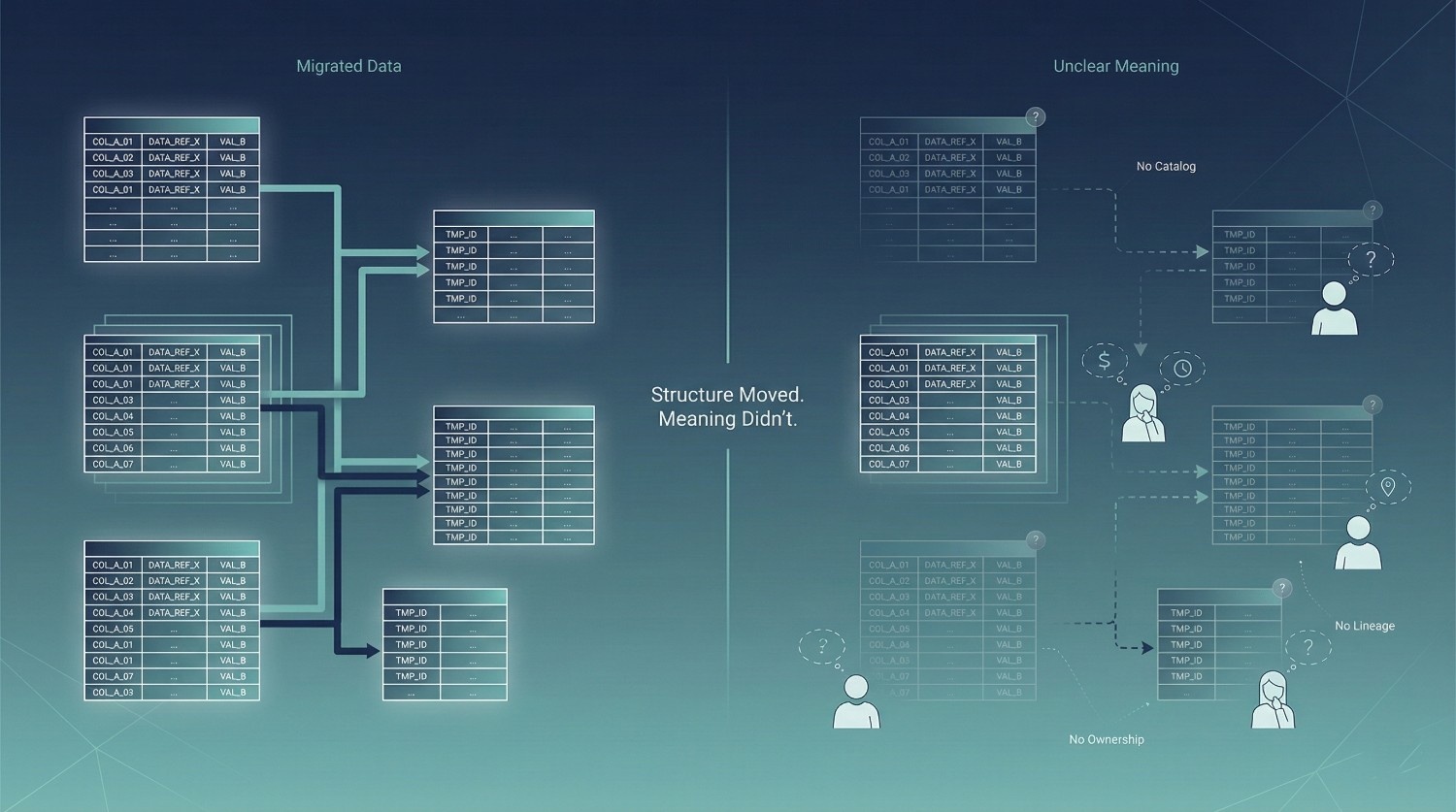

Bad Naming, No Catalog, No Documentation

Cloud data migration is often framed as a movement of data. In practice, it is a movement of meaning. When that meaning is poorly named, undocumented, or locked inside people’s heads, the migration may complete technically—but struggle to succeed functionally.

The platform exists. The data is there. Yet adoption stalls.

This is how it happens.

Column Names as Tribal Knowledge

Column names are the first interface between data and its users. When naming is careless or historically constrained, meaning becomes implicit rather than explicit.

Patterns like these are common:

- col_1, col_2, value_new

- flag2, flag_final, is_active_v3

- temp_status, status_override, status_fixed

These names rarely reflect current reality. They reflect moments in time—quick fixes, migrations layered on top of migrations, compromises made under pressure.

Over time, interpretation shifts from systems to people.

- Analysts learn which columns are “safe”

- Engineers know which flags to ignore

- Finance remembers which field matches the audit report

None of this knowledge is visible in the data itself. It survives through conversations, onboarding sessions, and Slack threads.

A cloud data migration copies the columns—but rarely the context. What was once manageable through proximity and familiarity becomes opaque when exposed to a broader audience.

Absence of a Data Catalog

As data volume and usage grow, the lack of a catalog often becomes more than an inconvenience—it becomes a blocker.

Without a catalog, there is:

- No discoverability

Users cannot find datasets confidently or understand which ones are authoritative. - No lineage

When numbers change, there is no clear path from dashboard to source. Debugging becomes guesswork. - No accountability

When definitions are unclear, ownership is implied rather than explicit. Questions circulate without answers.

In legacy environments, this gap is often tolerated. Access is limited. Users rely on personal networks to navigate the system.

Cloud data migration expands the audience. Self-service analytics, broader access, and faster iteration demand clarity. Without a catalog, the platform becomes a maze—technically powerful, practically unusable.

Documentation Written Too Late (or Never)

Documentation is often promised at the end of a migration.

“We’ll clean it up once things stabilize.”

“We’ll document after the cutover.”

“We’ll do a knowledge transfer later.”

Later often does not arrive.

Migrations stretch. Priorities shift. Engineers move on. When documentation is postponed, it often reflects the system as it was intended to work, not how it actually operates.

The cost becomes apparent when:

- Engineers who made key decisions leave

- New team members struggle to onboard

- Edge cases resurface without historical context

- Assumptions are reintroduced and re-broken

What disappears is not just documentation—but decision history. The rationale behind trade-offs, compromises, and exceptions is lost, leaving future teams to reverse-engineer intent from code.

Why Stakeholders Often Stop Using the New Platform

Trust is not built through availability. It is built through comprehension.

When stakeholders cannot answer simple questions—

- Where does this number come from?

- What does this field actually mean?

- Who owns this metric?

- Has this logic changed recently?

—they stop relying on the system.

They export data.

They build shadow spreadsheets.

They ask for one-off reports.

The cloud data migration may be complete on paper, but in practice, adoption collapses. The platform exists, yet decisions revert to old habits.

This is not resistance to change. It is rational behavior in the face of uncertainty.

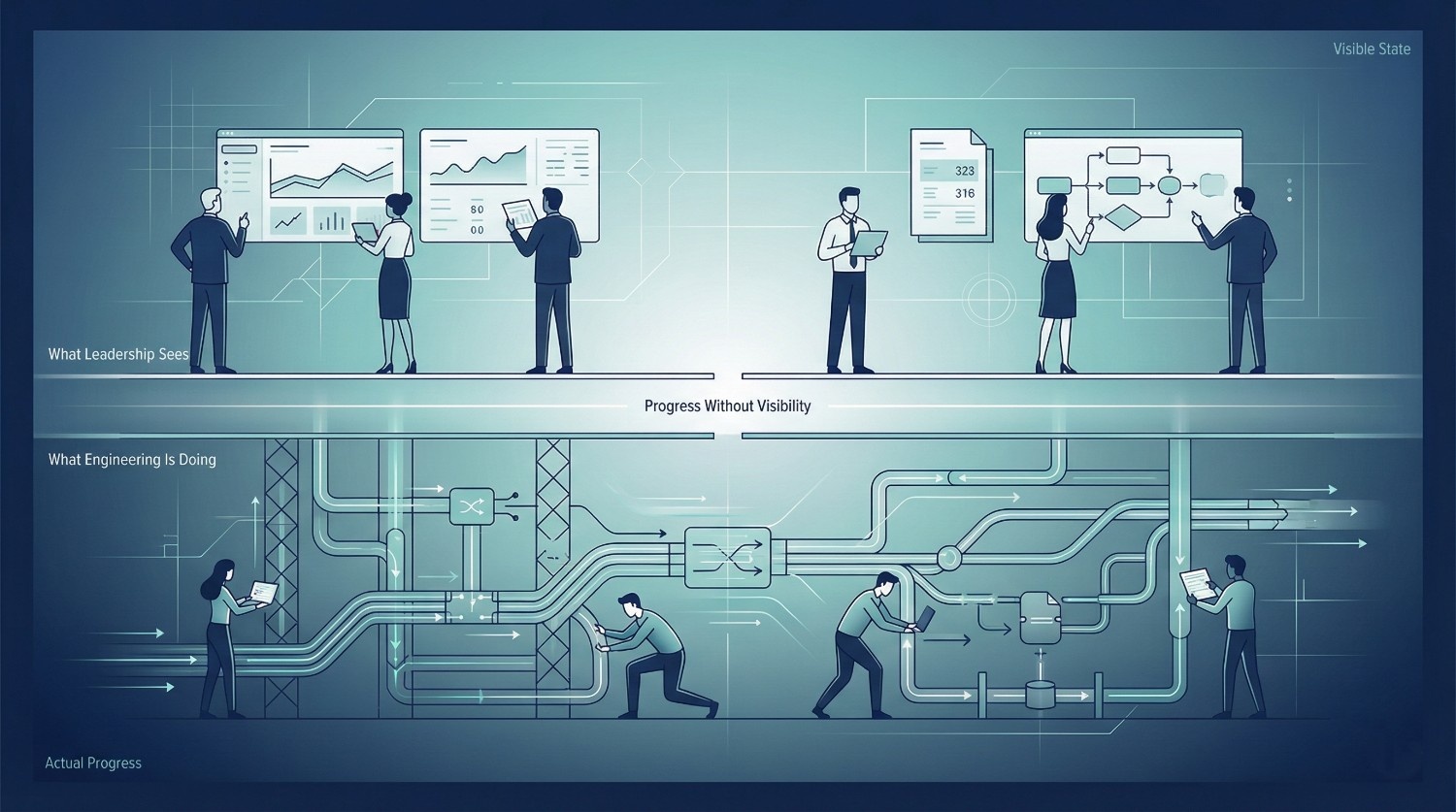

“Where Are the Results?” — The Visibility Gap

Cloud data migration efforts often begin with executive support and a degree of organizational patience. That patience is finite.

Unlike product launches or feature releases, migrations do not produce obvious artifacts. No new UI appears. No customer workflow improves overnight. From the outside, it can feel like months of effort have yielded nothing tangible.

This gap between effort and visibility is where many migrations quietly lose backing.

Migrations Don’t Ship Features

Most business stakeholders are conditioned to associate progress with visible change:

- A new dashboard

- A faster workflow

- A customer-facing improvement

- A clear before-and-after comparison

Cloud data migration delivers few of these by default.

Data moves behind the scenes. Pipelines are rebuilt. Validation happens in parallel systems. The work is essential—but largely invisible.

From a stakeholder’s perspective:

- There are no immediate UI changes

- Existing reports look the same

- Day-to-day workflows remain unchanged

Even when the migration is technically impressive, it can appear inert. Engineers know the foundation is being rebuilt. Stakeholders see only that nothing looks different yet.

This disconnect often creates doubt.

Stakeholders Need Proof, Not Promises

As timelines stretch, leadership questions shift.

Early on, executives ask how the migration will work. Later, they ask why it is still necessary.

Engineers respond with architectural explanations:

- Pipeline reliability

- Schema alignment

- Future scalability

- Long-term cost optimization

These are valid arguments—but they are not evidence.

Leadership is not opposed to architecture. They simply operate at a different altitude. They want to know:

- Can we trust the numbers more than before?

- Are decisions safer now?

- Is risk lower today than it was last quarter?

When progress is described in terms of pipelines built and jobs migrated, the answers remain abstract. Without visible outcomes, confidence often erodes—even if the work is sound.

The Cost of Invisible Progress

Invisible progress carries real consequences.

- Funding risk

Migrations compete with initiatives that show immediate ROI. When results are hard to demonstrate, budgets become easier to reallocate. - Priority drift

Teams are pulled into “urgent” work elsewhere. Migration effort becomes fragmented. Momentum slows. - “Over-engineered” labeling

Without visible wins, migrations are reframed as academic exercises—technically elegant, but disconnected from business value.

Once this narrative takes hold, it is often difficult to reverse. The migration becomes something to tolerate rather than champion. Support often persists just enough to avoid failure, but not enough to ensure success.

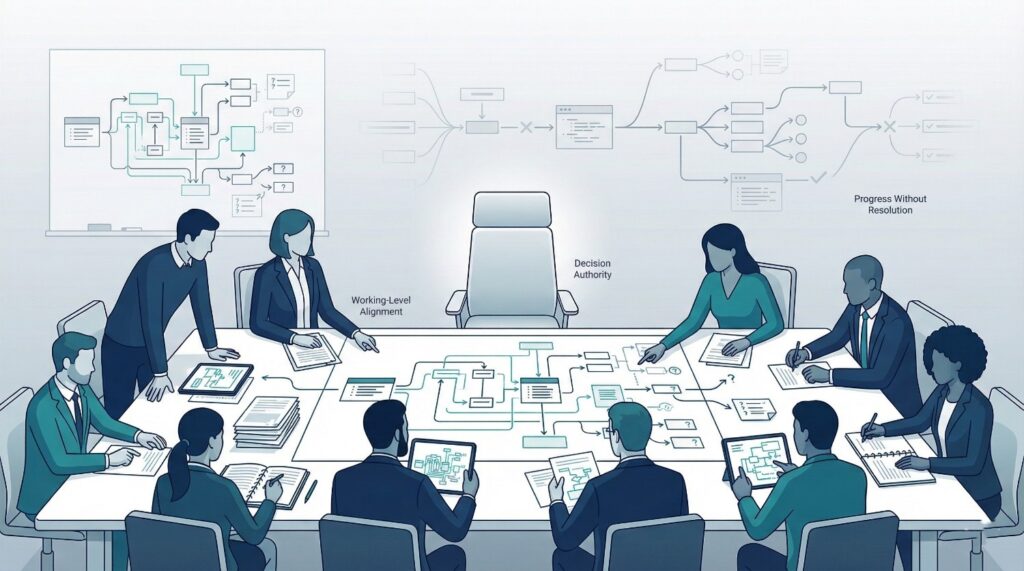

No Decision-Makers in the Room

Many cloud data migration initiatives struggle not because of bad choices—but because no one is empowered to make certain critical choices.

Decisions are often delegated downward, responsibility is diffused, and escalation paths are left undefined. The migration keeps moving technically, but directionally it drifts. Over time, progress slows—not from resistance, but from indecision.

Delegated Authority Without Real Authority

On paper, migrations appear well-governed. Roles are assigned. Owners are named. Meetings are scheduled.

In reality, authority is often delegated without mandate.

- Product managers without a data mandate

They can prioritize features, but not define metrics. They can schedule work, but not settle disagreements over definitions that affect revenue, forecasting, or incentives. - Analysts without escalation power

They understand the data deeply and spot inconsistencies early—but lack the authority to enforce a single definition or block conflicting implementations.

These roles are asked to “align stakeholders” without the ability to compel alignment. When disagreements arise, they can facilitate discussion—but not resolution.

The result is often a migration that moves forward cautiously, avoiding firm decisions to prevent conflict. Ambiguity remains encoded in logic. Temporary compromises harden into permanent structure.

Endless Back-and-Forth

When no one has the authority to decide, discussion often replaces progress.

This pattern is familiar:

- Slack threads that stretch across weeks

- The same questions reopened in different meetings

- Definitions revised, reverted, and revised again

- Logic rewritten to accommodate yet another exception

Each iteration feels reasonable. Each change feels small. Collectively, they drain momentum.

Engineers hesitate to finalize models because decisions feel provisional. Stakeholders hesitate to trust outputs because definitions feel unstable. The migration becomes reactive, constantly adjusting to unresolved debates rather than converging toward a stable state.

This is not collaboration—it is paralysis often disguised as process.

Why Migrations Stall Without Executive Input

Some decisions cannot be resolved at the working level.

They are inherently political:

- Which revenue number is “official” when sales and finance disagree?

- Which customer definition matters when growth and retention optimize differently?

- Which historical data is allowed to change—and which must remain untouched?

These choices affect performance metrics, incentives, and accountability. They create winners and losers. Avoiding them does not make them go away—it simply pushes them into code, where they reappear as complexity and distrust.

Engineers cannot resolve these questions alone. Analysts should not be asked to. Product managers cannot arbitrate them without mandate.

Executive input is often required to break the deadlock.

Without it, cloud data migration often stalls quietly—not with conflict, but with prolonged negotiation that produces motion without resolution.

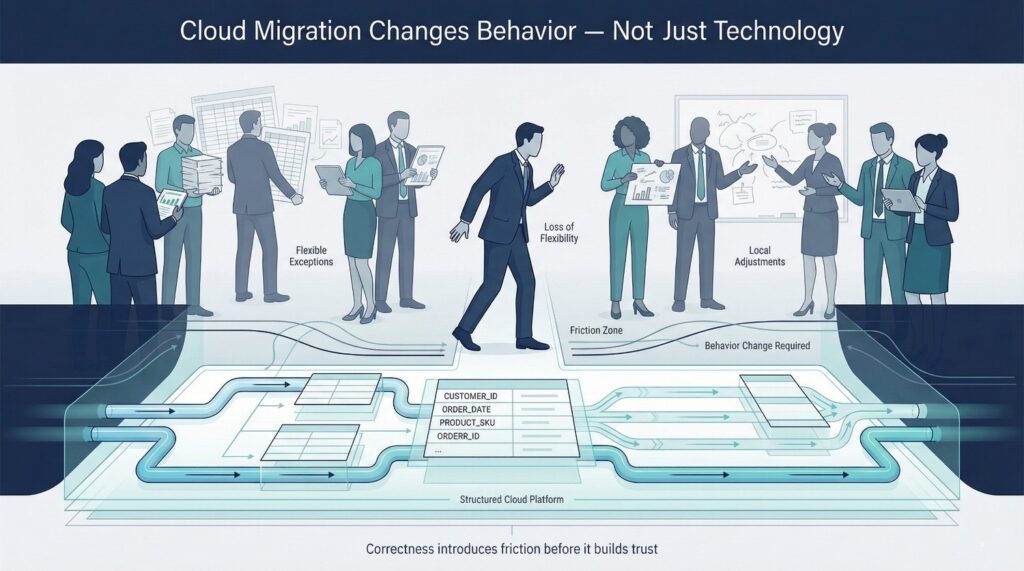

Business Resistance

Cloud data migration is often framed as a technical upgrade. For the business, it is something else entirely: a behavioral change.

New platforms do not just move data. They impose structure. They make inconsistencies visible. They reduce the room for informal workarounds that many teams have relied on for years.

Resistance often does not usually come from fear of technology. It comes from concern about losing flexibility.

New Platforms Force New Behaviors

Modern cloud platforms are often opinionated by design. They reward consistency and make ambiguity more costly.

Successful cloud data migration often requires the business to adopt new behaviors:

- Structured inputs

Free-text fields and ad-hoc overrides give way to controlled values, validations, and explicit states. - Consistent definitions

Metrics are meant to mean the same thing everywhere. Exceptions must be formalized, not improvised. - Accountability

When data is shared and visible, ownership becomes unavoidable. Someone has to stand behind each number.

These changes improve quality and trust—but they also remove escape hatches. Teams that were used to “fixing it later” or “adjusting in reporting” find that those habits no longer work.

When the Business Prefers the Old Mess

From the outside, resistance can look irrational.

Why defend broken spreadsheets?

Why cling to inconsistent reports?

Why resist cleaner, faster systems?

The answer is simple: the old mess is familiar.

- Known errors can be compensated for mentally

- Flexible processes allow quick exceptions

- Informal fixes avoid difficult conversations

A cloud data migration replaces this with constraint. It enforces rules where there used to be judgment. For some teams, that feels like loss—not improvement.

Correctness introduces friction. Flexibility feels faster, even when it produces worse outcomes.

So the business adapts in subtle ways:

- Adoption is delayed

- Shadow reports persist

- “Temporary” exports become permanent

- The new platform is bypassed rather than embraced

Resistance is often not explicit. It shows up as disengagement.

Cultural Mismatch with Cloud Discipline

Cloud platforms tend to amplify discipline.

They reward:

- Clear ownership

- Defined contracts

- Explicit assumptions

- Repeatable processes

Organizations that tend to thrive in this environment treat data as a product. Organizations that struggle treat data as an exhaust.

When culture favors speed, improvisation, and exception-handling over rigor, cloud data migration feels restrictive. Adoption slows not because the platform fails, but because the organization is misaligned with what the platform demands.

Engineers can build around resistance for a while. They can add exceptions. They can maintain backward compatibility. They can soften constraints.

Over time, the platform tends to reflect the culture—or the culture rejects the platform.

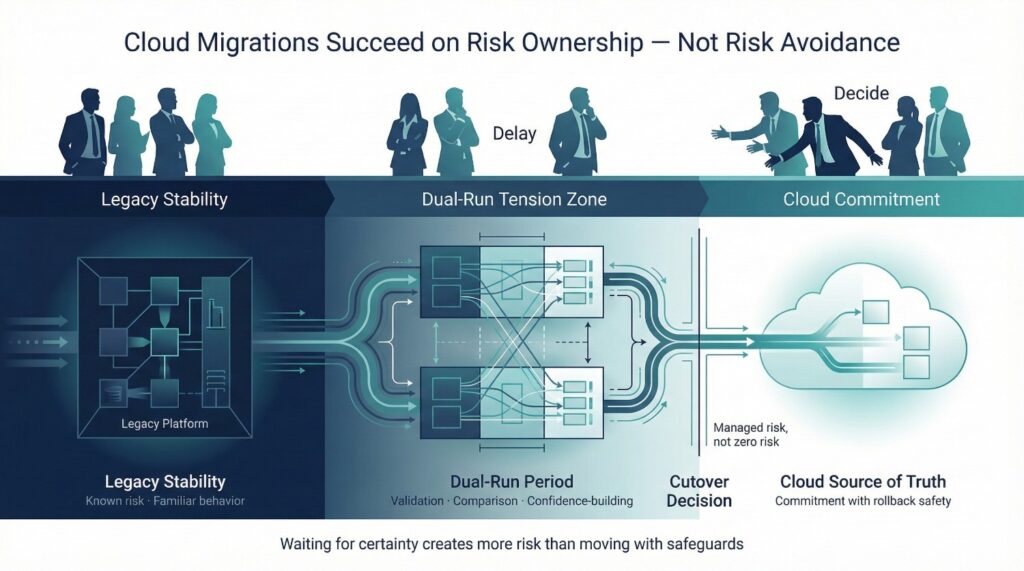

Leadership Risk Appetite

Every cloud data migration carries risk. What separates successful migrations from failed ones is not the absence of risk, but how leadership chooses to engage with it.

The most damaging outcomes often come from hesitation—where risk is endlessly deferred, diluted, and allowed to grow quietly. However, premature cutover without adequate validation has also caused high-profile failures.

Migrations Are Controlled Risk, Not Zero Risk

A cloud data migration is not a blind leap. It is a managed transition designed to reduce uncertainty over time, not eliminate it upfront.

Well-run migrations acknowledge risk explicitly and manage it through mechanisms such as:

- Dual-run periods

Legacy and cloud systems operate in parallel. Results are compared, discrepancies are surfaced, and confidence is built incrementally rather than assumed. - Cutover decisions

A defined point at which the organization commits to the new platform as the source of truth—based on agreed success criteria, not perfection. - Rollback plans

Not an expectation of failure, but an insurance policy. Knowing rollback is possible gives teams the confidence to move forward decisively.

These practices do not remove risk. They shape it—turning unknowns into measurable, time-bounded exposure.

A common mistake is treating migration as something that must be risk-free before it can proceed.

Avoiding Risk Creates Bigger Risk

When leadership becomes uncomfortable with visible risk, migrations slow. Dual-run periods stretch. Cutover is postponed. “Just one more validation” becomes a standing request.

This feels prudent. It is often the opposite.

Risk avoidance produces its own failure modes:

- Permanent dual systems

What began as a temporary safeguard becomes the default state. Two platforms, two sources of truth, and twice the operational overhead. - Escalating costs

Compute doubles. Tooling duplicates. Engineering time is split between maintenance and migration. Costs rise without delivering closure. - Data fragmentation

Logic diverges between systems. Fixes land in one place but not the other. Trust erodes as numbers drift subtly out of sync.

The longer this state persists, the harder it becomes to exit. At some point, the organization may no longer be “migrating”—it is effectively running two incomplete platforms.

The Cost of Indecision

Indecision has a signature phrase:

“Let’s wait one more quarter.”

Each delay sounds reasonable in isolation. Collectively, they drain momentum.

Engineers lose urgency.

Stakeholders lose interest.

The migration stops feeling temporary.

Over time, teams may lose clarity on what condition would actually trigger a decision. The project continues because stopping would admit failure—but finishing would require risk.

This is how momentum dies quietly.

Not with resistance.

Not with technical collapse.

But with leadership seeking certainty where only managed uncertainty is possible.

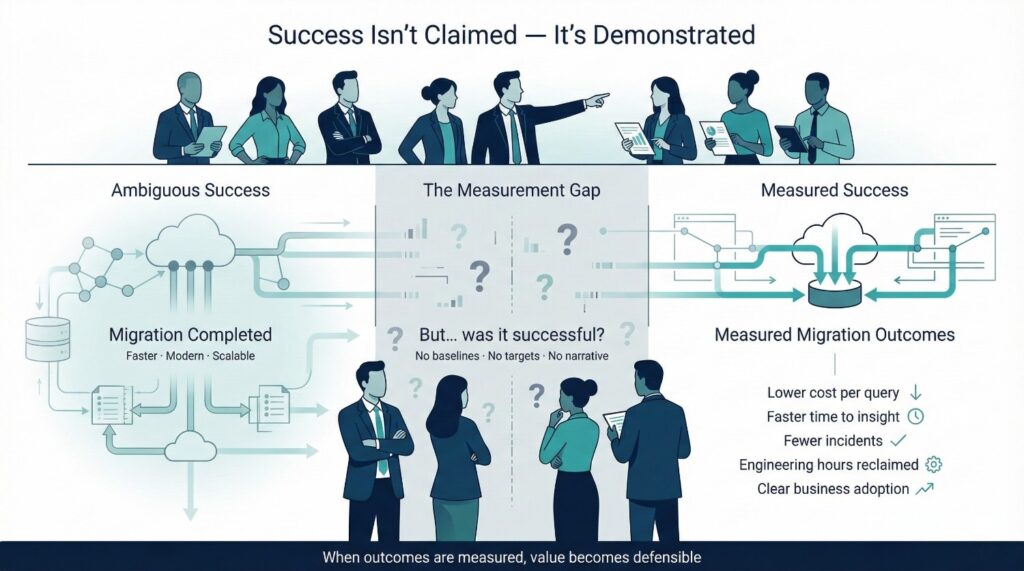

Can We Actually Measure Success?

One of the most revealing questions in any cloud data migration is deceptively simple:

How will we know when this has succeeded?

In many organizations, there is no clearly articulated answer. The migration moves forward, pipelines are built, and systems are switched—but success remains vaguely defined. Without measurement, even objectively strong outcomes can feel disappointing.

Many Migrations Lack Success Metrics

Ask teams how they will judge a cloud data migration, and the answers are often imprecise.

- “It’s faster now.”

- “It’s more modern.”

- “It’s scalable.”

None of these are wrong. They are also insufficient.

Faster than what?

Modern in which way?

Scalable for which workload?

Without baseline comparisons and explicit targets, these claims are difficult to validate—or defend. When leadership asks whether the migration was worth the cost, teams are left with anecdotes instead of evidence.

This is how technically sound migrations become politically fragile.

What Should Be Quantified

Not everything valuable can be measured, but migrations that measure little often feel unsuccessful.

Effective migrations quantify impact across multiple dimensions:

- Cost per query

Not just total spend, but efficiency. Are teams paying less to answer the same questions—or answering more with the same budget? - Time to insight

How long does it take from a business question to a reliable answer? Reduced latency here directly affects decision quality. - Incident reduction

Fewer broken dashboards, fewer data quality escalations, fewer late-night reconciliations. - Engineering hours saved

Time no longer spent firefighting pipelines or manually validating reports can be redirected to higher-leverage work. - Business adoption

Are teams actually using the new platform as their primary source of truth—or quietly reverting to old systems?

These metrics translate technical improvements into business outcomes. They create a shared language between engineering and leadership.

Why Unmeasured Migrations Feel Like Failures

When success is not measured, value is difficult to narrate.

Leadership cannot explain the return.

Teams cannot defend the investment.

Future initiatives inherit skepticism.

Even if the platform is objectively better, the absence of metrics often creates doubt. The migration becomes a cost center rather than an enabler. Confidence erodes—not because the work failed, but because its impact was never made visible.

Cloud data migration does not need perfect metrics. It needs credible ones.

Without them, success remains subjective—and subjectivity is where trust often breaks down.

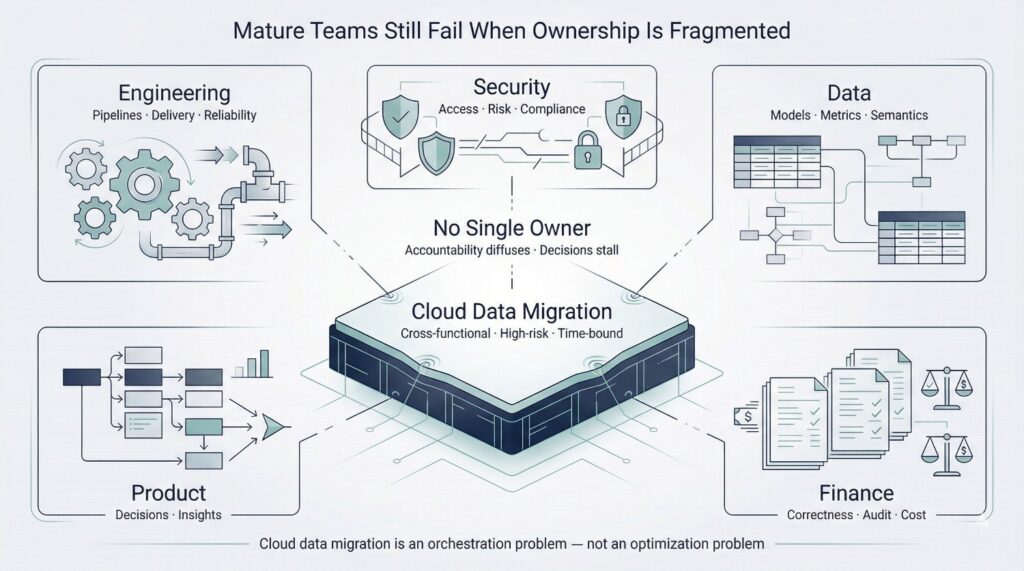

Why This Keeps Happening (Even in Mature Teams)

At this point, the pattern should be clear.

The failures described in this article are typically not the result of incompetence. They recur even in organizations with experienced engineers, modern tooling, and strong leadership. They appear in companies that have migrated before—and still struggle again.

A primary reason is structural.

Cloud data migration does not belong cleanly to any single function.

It sits uncomfortably between:

- Engineering, which builds and operates pipelines

- Data, which defines models, metrics, and quality expectations

- Product, which depends on analytics to guide decisions

- Finance, which cares about correctness, audits, and cost

- Security, which governs access, risk, and compliance

Each group touches the migration. Often none owns it end-to-end by default.

The Ownership Gap

In many organizations, ownership follows existing reporting lines. Cloud data migration cuts across them.

Engineering may be accountable for delivery—but not for business definitions.

Data teams may understand semantics—but lack authority to enforce decisions.

Product teams feel the impact—but cannot prioritize platform work.

Finance demands correctness—but engages late.

Security reviews risk—but does not own outcomes.

The result is often a vacuum.

Decisions stall because they do not belong to any one function. Accountability diffuses. Progress depends on informal coordination rather than formal mandate.

This is one reason migrations rely so heavily on individual heroics.

Why Heroics Don’t Scale

When ownership is unclear, success depends on people willing to go beyond their role:

- Engineers who negotiate definitions across teams

- Analysts who chase approvals without authority

- Managers who absorb risk informally to keep momentum

- Leaders who intervene only when things are already late

These efforts can save individual migrations—but they are fragile. They depend on specific people, institutional memory, and personal influence.

When those people move on, the system often resets. The next migration repeats the same mistakes.

Mature teams still fail because maturity at the functional level does not guarantee maturity at the interface between functions.

Orchestration, Not Optimization

Cloud data migration is not a problem of doing any one thing better. It is a problem of orchestration.

Success requires:

- Clear end-to-end ownership

- Explicit decision rights

- Defined success metrics

- Visible progress tied to business outcomes

- Leadership willing to make bounded decisions

Without this structure, even excellent teams can operate at cross purposes. The migration advances technically while stalling organizationally.

This is why the same failure modes often appear again —not because teams don’t learn, but because the system they operate in has not materially changed.

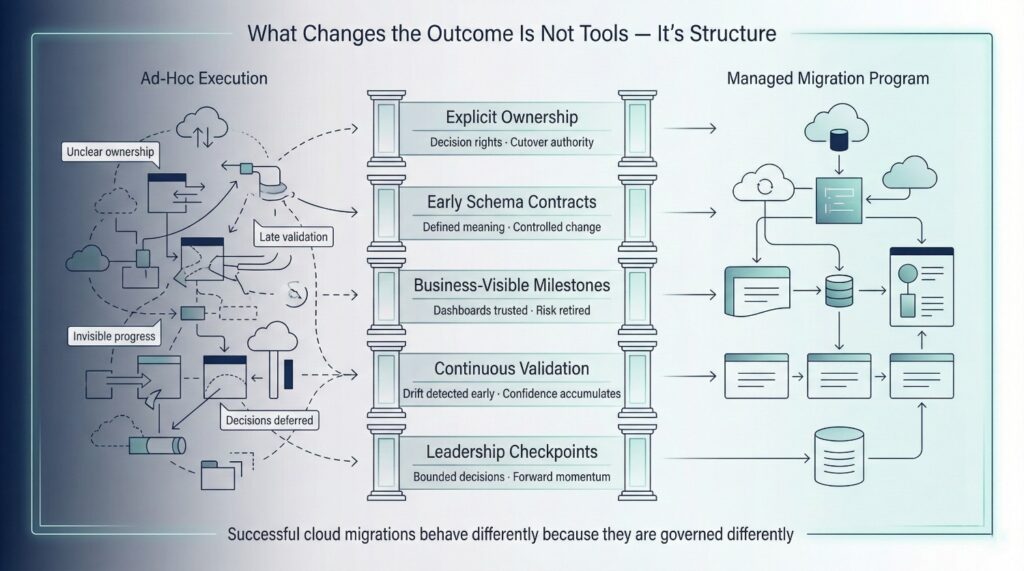

What Actually Makes Cloud Migrations Succeed

After examining why cloud data migrations fail—even with strong teams—the natural question is what actually changes the outcome.

Not tools.

Not frameworks.

Not hero engineers working longer hours.

Successful cloud data migration often looks different because it is treated differently. The organizations that succeed tend to approach migration as a managed program, not merely an extended engineering project. They design for alignment, not just execution.

The principles below are deliberately high-level. They are not tactics. They are structural choices that change how everything else behaves.

Explicit Ownership and Decision Rights

Successful migrations begin by answering a question most teams avoid:

Who owns the migration end to end?

Not who builds pipelines.

Not who reviews security.

Not who validates dashboards.

Who has the authority to:

- Resolve definition conflicts

- Accept trade-offs

- Declare readiness

- Trigger cutover

This ownership is explicit, documented, and visible in successful programs.

Decision rights are clear before disagreements arise—not negotiated mid-crisis.

When ownership exists, debates tend to converge. When it does not, ambiguity spreads into schemas, logic, and timelines.

Early Schema Contracts

Winning migrations treat schemas as agreements, not byproducts.

Key datasets are defined early with:

- Clear field meanings

- Ownership assignments

- Change expectations

- Downstream impact awareness

This does not mean schemas never evolve. It means evolution is intentional, reviewed, and understood.

Early schema contracts reduce rework, help prevent silent breakage, and reduce the likelihood that engineers become default arbitrators of business meaning.

Business-Visible Milestones

Successful cloud data migration is rarely invisible.

Progress is framed in terms the business can recognize:

- Metrics reconciled

- Dashboards trusted

- Decisions enabled

- Incidents eliminated

These milestones are not merely cosmetic. They are signals that risk is being retired and confidence is increasing.

When stakeholders can see progress, support grows. When progress is only visible in pipelines and diagrams, patience erodes.

Continuous Validation

Instead of treating validation as a final phase, successful migration tends to validate continuously.

- Old and new systems are compared regularly

- Differences are investigated, not explained away

- Drift is surfaced early, when fixes are cheap

- Trust is built incrementally, not requested at cutover

This turns validation from a gate into a feedback loop. Confidence accumulates gradually instead of being demanded all at once.

Leadership Involvement at Defined Checkpoints

Leadership does not need to be involved constantly—but it must be involved deliberately.

Successful migrations define:

- When executive decisions are required

- What criteria trigger escalation

- What trade-offs leadership is being asked to accept

This prevents two failure modes:

- Leaders disengaging until it’s too late

- Teams stalling while waiting for implicit approval

When leadership engagement is structured, decisions are more likely to happen on time—and momentum is easier to preserve.

Final Thoughts

If there is one lesson that repeats across failed cloud data migration efforts, it is this:

The failures are primarily systemic, not purely technical.

They typically do not originate in weak engineers, poor tooling, or flawed architectures. They emerge from unclear ownership, deferred decisions, invisible progress, and leadership hesitation. Engineering absorbs these gaps until complexity, distrust, and delay become indistinguishable from failure.

Cloud data migrations tend to succeed for a different set of reasons.

They succeed when:

- Decisions are explicit

Definitions are chosen, trade-offs are acknowledged, and ambiguity is resolved rather than encoded into pipelines. - Ownership is clear

Someone is accountable for outcomes end to end—not just for building systems, but for declaring them ready. - Progress is visible

Risk is retired in ways the business can see, measure, and trust—not hidden behind technical milestones.

When these conditions are met, engineering excellence is more likely to compound. When they are absent, even the strongest teams struggle.

The final takeaway for leadership is straightforward:

Treat cloud data migration as an organizational change program ––not merely an engineering task.

The cloud does not consistently reward optimism, avoidance, or perfectionism. It rewards clarity, discipline, and decision-making.

When organizations design for that reality, migrations are far more likely to shift from being high-risk bets to controlled repeatable transitions that leave the platform stronger than before.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

No. While engineering execution is critical, many failures occur due to unclear ownership, unresolved business definitions, governance friction, and lack of visible outcomes. The technical layer often works exactly as designed—what fails is the surrounding structure that should guide decisions and accountability.

Because experienced engineers cannot compensate indefinitely for missing decision rights, ambiguous schemas, or delayed leadership decisions. When business meaning is unclear or ownership is diffuse, engineers end up encoding uncertainty into pipelines, which eventually erodes trust and momentum.

No—and trying to do so often delays progress indefinitely. What matters is identifying which data quality issues block trust and decision-making. Migration surfaces data problems that were previously hidden; the goal is to address them incrementally with clear ownership, not to reach theoretical perfection upfront.

Cloud platforms expose inefficiencies that legacy systems hide. Conflicting definitions, duplicated logic, and unclear ownership become more visible when data is centralized and reused. The slowdown is often organizational, not infrastructural.

As short as possible—but long enough to build confidence. Dual-run periods should have explicit exit criteria. When they are left open-ended, they often become effectively permanent, driving up cost and fragmenting trust rather than reducing risk.

Someone with end-to-end authority across engineering, data, and business definitions. Not a committee, and not just a technical lead. Successful migrations have a clearly empowered owner who can resolve conflicts, accept trade-offs, and declare readiness.

Because they often cannot understand it. Poor naming, missing documentation, lack of lineage, and shifting definitions make it hard to explain where numbers come from. When trust drops, usage drops—regardless of performance or scale.

Useful indicators include cost per query, time to insight, reduction in data incidents, engineering hours saved, and—most importantly—business adoption. If teams still rely on old systems or shadow reports, the migration has not truly succeeded.

Yes—but it must be structured. Leadership does not need to attend every meeting, but must be present at defined checkpoints where trade-offs, risk acceptance, and cutover decisions are required. Without this, migrations often stall quietly.

Often because success criteria were never clearly defined. Without explicit end states, migrations drift into permanent transition phases, where no one feels confident enough to declare completion—or failure.

Clarity. Clear ownership, clear definitions, clear metrics, and clear decision paths. When these are in place, technical excellence compounds. When they are absent, even mature teams struggle.