Table of Contents

Introduction

The most dangerous assumption CTOs make about cloud data migration is deceptively simple:

“If we plan carefully enough, we can make this zero risk.”

It sounds responsible. It signals caution. It reassures leadership.

And in practice, it often increases the probability of failure.

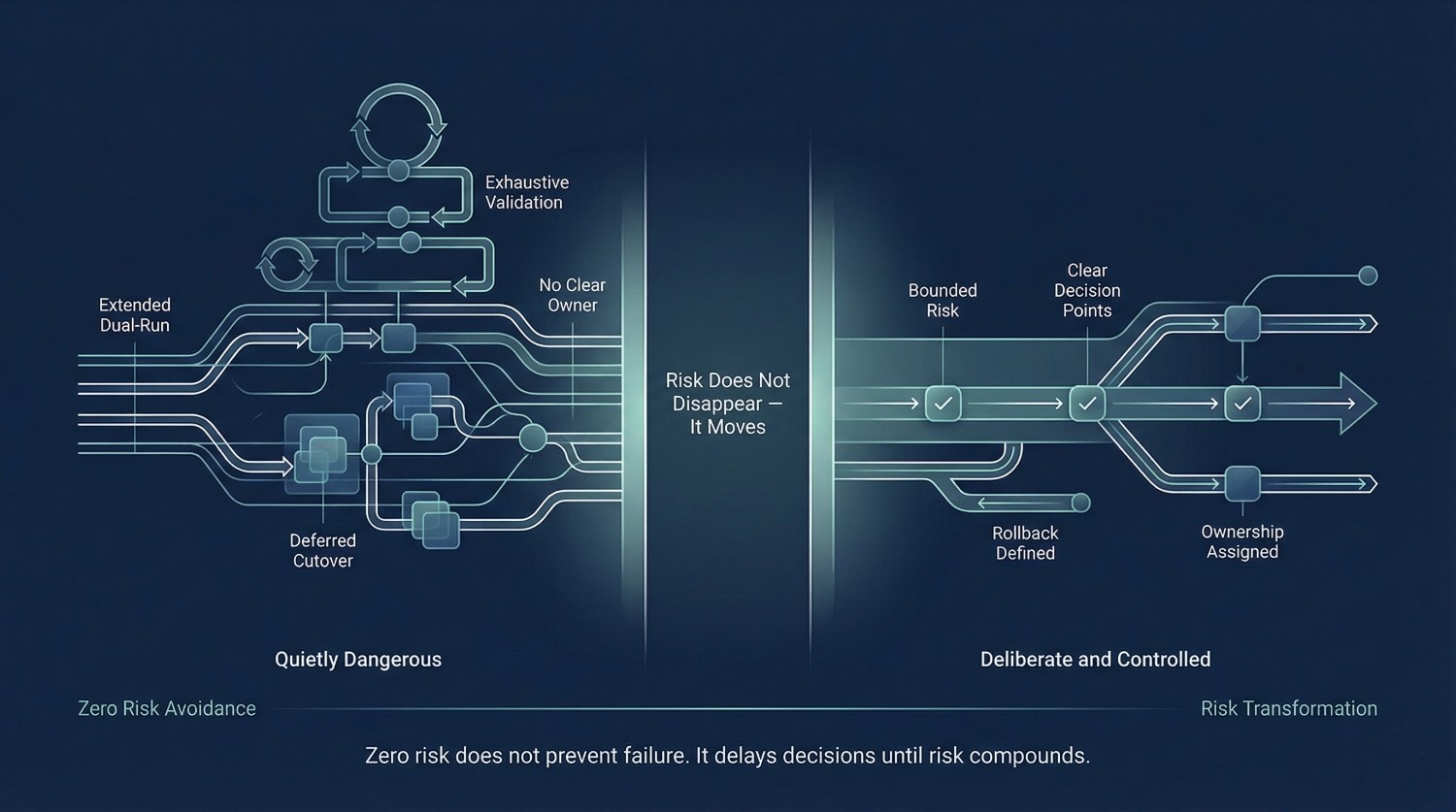

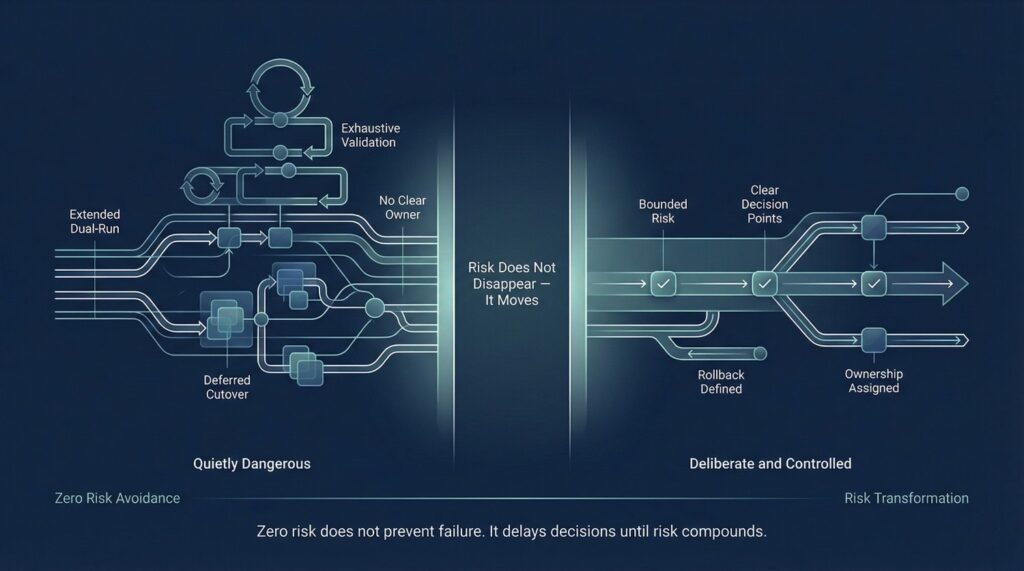

Cloud data migration is not a process where risk can be eliminated. It is a process where risk is transformed—from one shape into another, from hidden to visible, from unmanaged to deliberate. When organizations pursue zero risk, they don’t remove uncertainty. They postpone decisions, stretch timelines, and allow new risks to accumulate in less visible forms.

This is why some of the most painful migration failures happen in organizations that prioritized extreme risk avoidance over timely decision-making.

Why “Zero Risk” Increases Failure Probability

The pursuit of zero risk changes behavior in predictable ways:

- Cutovers are delayed indefinitely “until we’re more confident”

- Dual systems remain live far longer than intended

- Validation becomes exhaustive rather than risk-prioritized

- Decisions are deferred to avoid accountability

Each choice feels prudent in isolation. Collectively, they produce fragility.

Instead of one controlled transition, the organizations often end up running multiple partial systems, duplicated logic, and conflicting sources of truth. Costs rise. Trust erodes. Engineers spend more time reconciling data than improving it. Eventually, leadership is forced to accept a much larger, less controlled risk than the one it originally tried to avoid.

Zero risk framing does not prevent failure. It often repackages it in less visible forms.

Cloud Data Migration as Risk Transformation

A cloud data migration does not move an organization from “risky” to “safe.” It moves risk across dimensions:

- From hidden data inconsistencies to visible discrepancies

- From operational fragility to governance pressure

- From slow, manual checks to fast, automated validation

- From implicit trust in legacy systems to explicit confidence-building

The question is not whether risk exists. It is where it lives, how visible it is, and who owns it.

Mature CTOs understand that migrations succeed when risk is surfaced early, bounded deliberately, and reduced over time—not when it is denied.

The CTO’s Real Responsibility

For CTOs, cloud data migration is not primarily an engineering challenge; it is fundamentally a risk-leadership challenge.

The real responsibility is not to promise safety. It is to decide:

- Which risks should be accepted temporarily

- Which risks must be controlled aggressively

- Which risks should be transferred through process, tooling, or contracts

- Which risks are worse than the migration itself

These decisions cannot be delegated entirely to engineers or avoided through process alone. They require judgment, trade-offs, and visible ownership.

When CTOs defer this role—by aiming for zero risk instead of managed risk—migrations drift. When they embrace it, migrations become predictable.

What This Article Will Help CTOs Do

This article is written for CTOs who want to approach cloud data migration with clarity rather than false reassurance.

It will help you:

- Identify real migration risks, not just the loud or familiar ones

- Separate perceived risk from actual risk, especially where comfort and safety are confused

- Build a risk-aware migration strategy that leadership, finance, security, and engineering can all stand behind

Cloud data migration is not about avoiding risk. It is about choosing the right risks to take—on purpose.

The sections that follow will break down what those risks actually are, why they are often misunderstood, and how CTOs can lead migrations that are safer because they are honest about uncertainty, not in spite of it.

Data Migration Consulting often exists primarily to prevent this trust erosion — not just to move data.

Why “Zero Risk” Is an Anti-Pattern

The idea of zero risk feels responsible—especially at the CTO level. It signals caution, control, and maturity. But in the context of cloud data migration, zero-risk thinking is not conservative. It is often structurally dangerous.

Not because risk disappears when ignored—but because it moves into places where it is harder to see, measure, and manage.

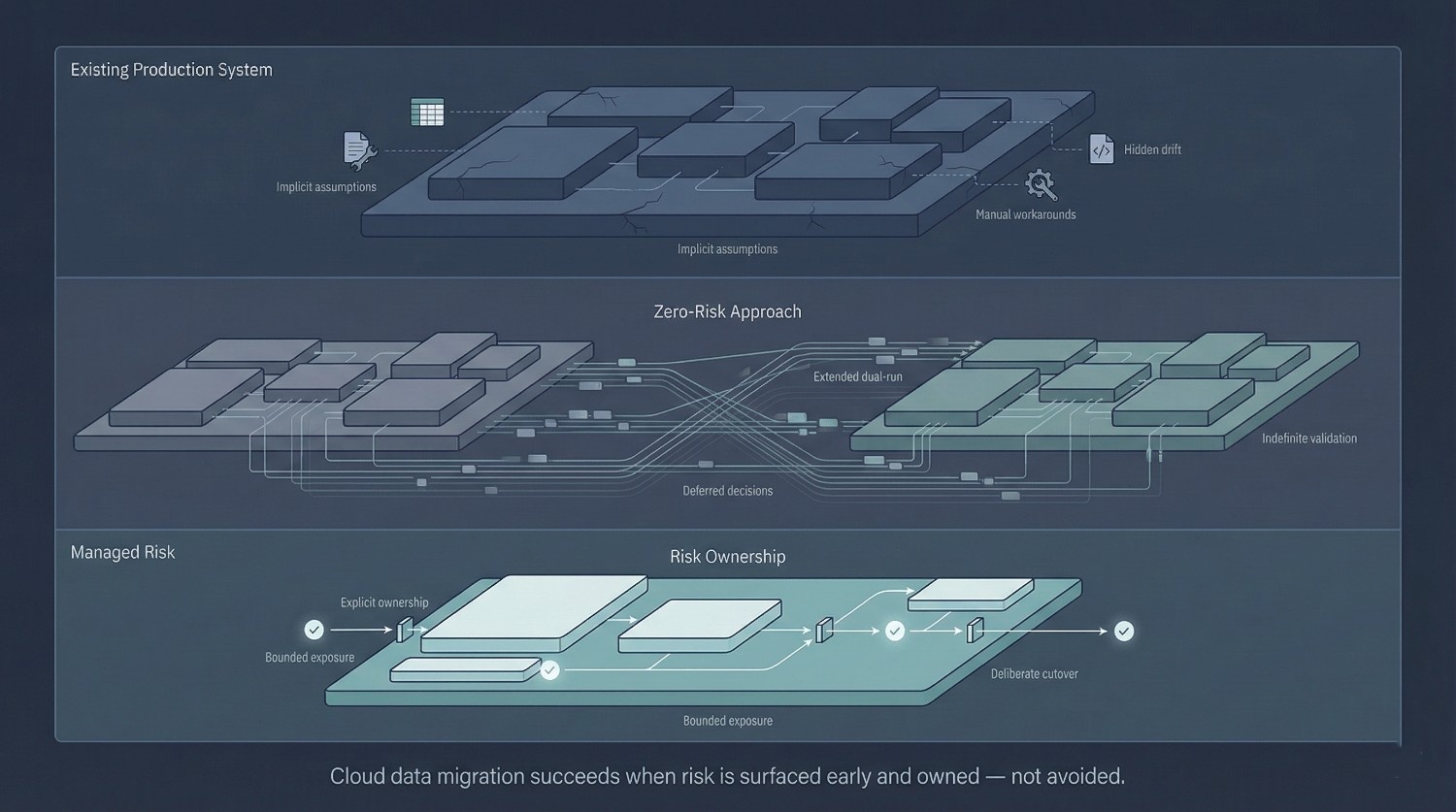

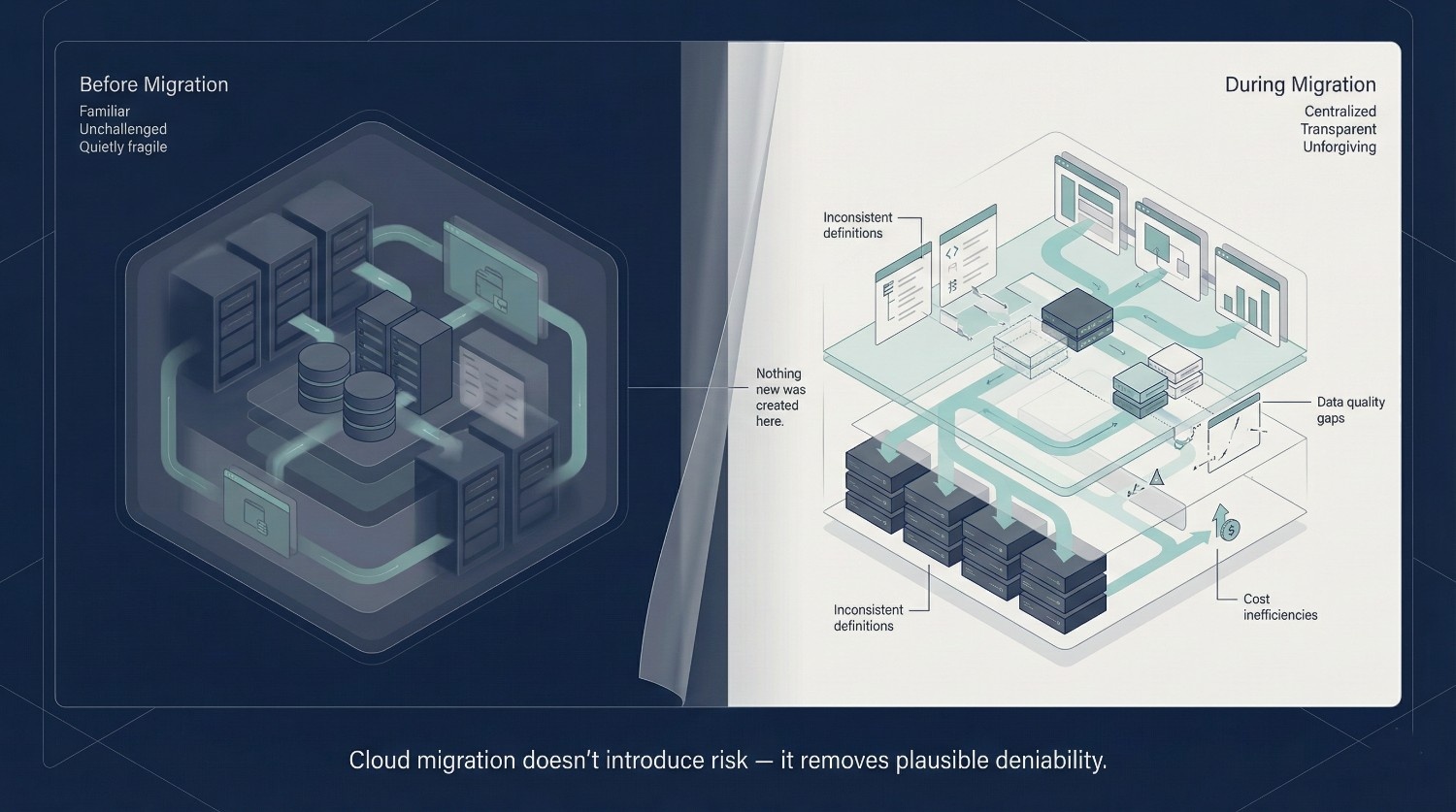

All Production Systems Already Carry Risk

A common mental trap in migration planning is treating the existing system as the “safe baseline.”

It is not.

Every production data platform already carries some level of risk. The difference is that most of it is invisible.

Legacy systems often appear stable because they are familiar—not necessarily because they are robust. Over time, hidden risks accumulate quietly:

- Silent data corruption

Historical backfills that were never reconciled, transformations applied inconsistently, or fields whose meaning drifted without correction. The numbers “look right” because no one is checking them closely anymore. - Manual workarounds

Spreadsheets, one-off scripts, and undocumented fixes compensate for known issues. These are operational crutches, not controls—but they become embedded in daily workflows. - Knowledge concentration

Critical understanding lives in a few people’s heads. When they leave, systems don’t break immediately—they degrade slowly, unpredictably, and expensively.

Calling these systems “safe” is often a category error. They are merely unchallenged.

A cloud data migration doesn’t introduce risk into a pristine environment. It forces existing risk into the open.

Zero-Risk Thinking Leads to Paralysis

When leadership treats zero risk as the goal, behavior often changes—without explicit decision to do so.

The migration often begins to slow in familiar ways:

- Endless reviews

Every change is scrutinized repeatedly, not because it is dangerous, but because no one wants to be accountable for visible risk. - Overextended dual-runs

Parallel systems persist “just a little longer” to build confidence that never fully arrives. Temporary safety nets become permanent architecture. - Indefinite postponement of cutover

There is always one more edge case, one more validation, one more stakeholder who needs reassurance.

None of this looks reckless. It looks careful.

But this caution has a cost. Engineers context-switch. Logic diverges. Costs double. Confidence erodes. The migration loses momentum—not through failure, but through exhaustion.

At some point, the organization may no longer be migrating; it is simply maintaining complexity.

The Paradox

Here is the paradox that zero-risk thinking fails to recognize:

The risks you avoid making visible are often the ones most likely to cause harm later.

By delaying decisions and avoiding cutover, organizations trade short-term comfort for long-term fragility:

- Two systems drift out of sync

- Fixes land in one place but not the other

- Data definitions diverge

- Costs escalate without resolution

- Trust erodes quietly

These risks are harder to quantify and harder to unwind than the original migration risk.

What started as an effort to be safe turns into a system that is brittle, expensive, and politically untouchable.

Zero-risk framing does not protect the organization; it often distributes risk across time, teams, and systems until ownership becomes unclear.

The goal of cloud data migration is not to eliminate risk. It is to surface it early, bind it deliberately, and reduce it over time.

CTOs who understand this do not ask, “How do we make this risk-free?”

They ask, “Which risks are acceptable—and which ones are worse than the migration itself?”

That shift in thinking is where successful migrations begin.

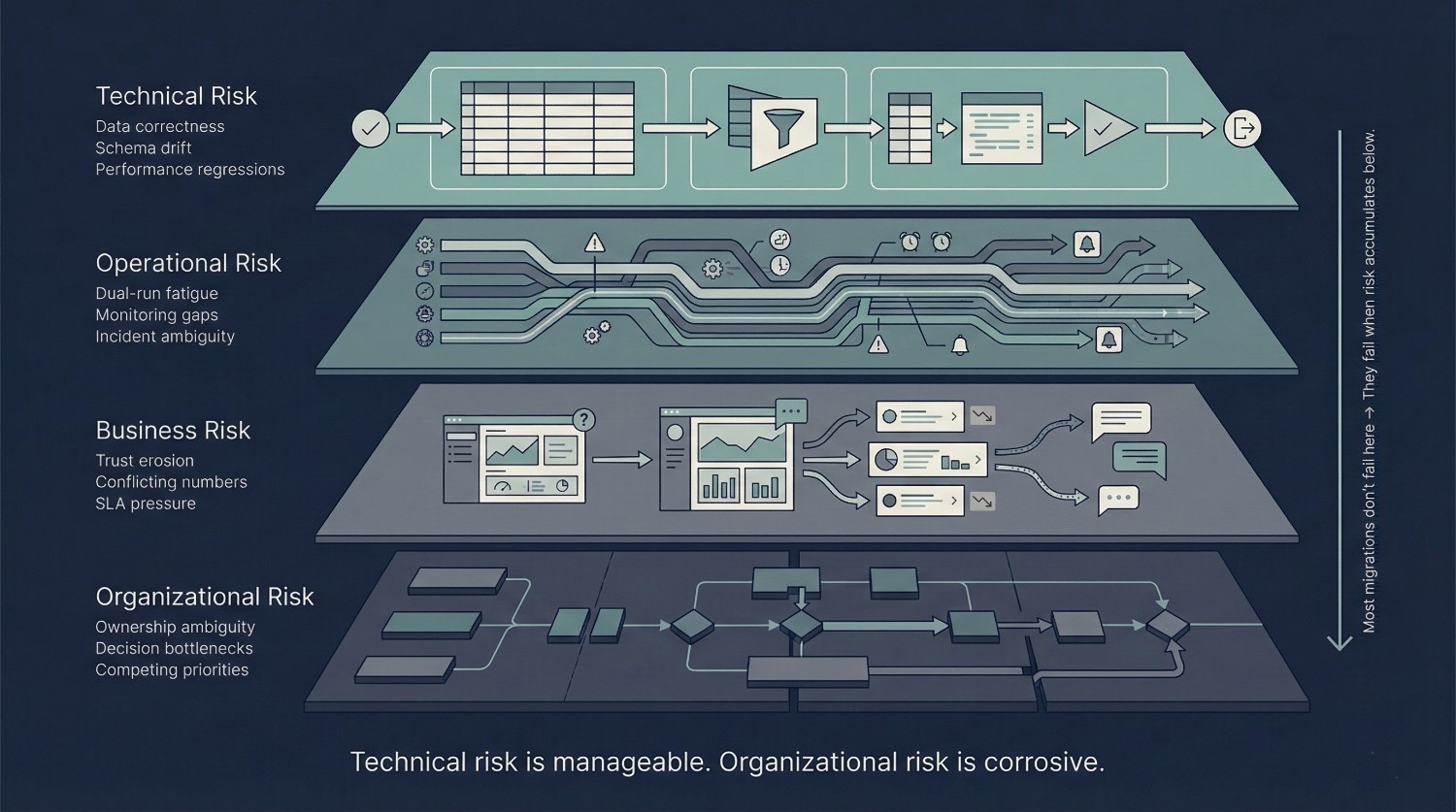

The Four Categories of Migration Risk CTOs Must Understand

One of the biggest mistakes CTOs make during cloud data migration is treating “risk” as a single, undifferentiated concern. In reality, migration risk comes in distinct categories, each behaving differently and requiring different forms of leadership.

When these risks are blurred together, technical mitigations are applied to non-technical problems—and migrations often fail in predictable ways.

Technical Risk

Technical risk is the most visible and the most discussed. It is also the easiest to reason about.

Common technical risks include:

- Data correctness

Mismatches between legacy and cloud outputs, incomplete backfills, or subtle transformation errors. - Schema drift

Upstream systems changing during migration without contracts or alerts, causing downstream breakage weeks later. - Pipeline reliability

Failed jobs, retry storms, partial loads, or brittle dependencies. - Performance regressions

Queries that run slower than expected, workloads that contend for resources, or cost-performance trade-offs that weren’t modeled.

These risks are real—but they are generally tractable. Engineers can detect them, perform tests for them, or fix them. Given time and clarity, technical risk typically trends downward during a well-run migration.

This is not where most migrations ultimately collapse.

Operational Risk

Operational risk emerges when systems move into production reality—on-call rotations, incident response, and day-to-day reliability.

Typical examples include:

- On-call burden increases

Two systems must be monitored, debugged, and supported simultaneously. - Incident response gaps

Teams are unsure which system is authoritative during incidents, delaying resolution. - Incomplete monitoring

New pipelines exist, but alerts, dashboards, and runbooks lag behind. - Dependency breakage

Downstream consumers—BI tools, reverse ETL, ML pipelines—fail silently or unpredictably.

Operational risk is dangerous in part because it creates fatigue. Engineers lose confidence in the system not because it is broken, but because it is noisy and ambiguous under pressure.

Still, like technical risk, operational risk can be managed with discipline and investment.

It is rarely fatal on its own in otherwise healthy migrations.

Business Risk

Business risk is where migrations begin to feel politically fragile.

It manifests as:

- Reporting discrepancies

Finance, sales, and product see different numbers for the “same” metric. - Stakeholder trust erosion

Leaders stop believing dashboards—even when they are correct. - SLA violations

Reports are late, data is missing, or operational metrics lag behind expectations. - Customer-facing impact

Decisions based on incorrect or delayed data affect pricing, support, or user experience.

Business risk is not about correctness alone. It is about confidence.

Once stakeholders stop trusting the data, adoption stalls. Shadow systems reappear. The migration loses legitimacy—even if the platform is technically sound.

Organizational Risk

Organizational risk is among the least discussed—and often the most destructive.

It includes:

- Ownership ambiguity

No one owns definitions, cutover decisions, or end-state success. - Decision bottlenecks

Conflicts escalate slowly or not at all. Important choices linger unresolved. - Competing priorities

Migration work is continually deprioritized in favor of visible feature delivery. - Cultural resistance

Teams resist the discipline cloud platforms impose, preferring familiar ambiguity.

Organizational risk does not trigger alerts. It does not throw errors. It accumulates quietly until progress stalls and momentum evaporates.

This is where most failed migrations ultimately fail.

The Key Insight CTOs Must Internalize

Many cloud data migrations do not fail because of technical risk alone.

They fail when organizational risk overwhelms the system.

Technical problems are solvable. Sustained organizational indecision is corrosive.

CTOs who treat migration risk as primarily technical end up investing heavily in controls that do not address the real failure modes. CTOs who recognize organizational risk early can design governance, ownership, and decision structures that keep the migration moving—even when uncertainty remains.

Understanding these four categories is the foundation of a risk-aware migration strategy. The sections ahead will focus on how CTOs can actively manage—not avoid—these risks without falling into the zero-risk trap.

Risk Already Exists — Migration Just Makes It Visible

One of the most common reactions during cloud data migration is this:

“We didn’t have these problems before we started migrating.”

In the vast majority of cases, that statement is false.

The problems existed already. The migration simply removed the layers that were hiding them.

Cloud data migration does not introduce most categories of risk. It exposes them—earlier, faster, and at a scale that makes them impossible to ignore.

What Cloud Platforms Expose

Modern cloud platforms are more unforgiving in certain ways than legacy systems. They surface issues that older environments allowed teams to work around quietly.

Most commonly, migrations expose:

- Inconsistent definitions

Metrics that were assumed to be shared turn out to mean different things across teams. Legacy separation masked the disagreement; centralization reveals it. - Poor data quality

Missing values, malformed records, and ad-hoc fixes that were tolerated in downstream reporting become visible when data is reused broadly and validated continuously. - Cost inefficiencies

Inefficient queries, redundant transformations, and underutilized resources stand out immediately when usage and spend are transparent.

None of these issues are typically new. What is new is the lack of plausible deniability.

Why Teams Blame the Migration

When previously hidden problems become visible, the migration becomes the obvious culprit.

This is understandable.

The timing aligns. Confidence drops. Stakeholders see discrepancies for the first time. It feels safer to attribute discomfort to the change rather than confront the underlying causes.

Blaming the migration also offers a convenient escape hatch:

- Pause the rollout

- Extend dual-run

- Revert to the “stable” system

- Defer difficult decisions

This response reduces short-term anxiety—but at a cost.

The Danger of Reverting Instead of Fixing

Reverting to legacy systems does not eliminate risk; it primarily re-hides it.

The underlying problems remain:

- Definitions are still inconsistent

- Data quality is still uneven

- Costs are still inefficient

- Knowledge is still concentrated

The organization simply returns to a state where these issues are less visible—and therefore less urgent.

In many cases, the migration now carries a stigma. Future attempts inherit skepticism. Teams become more risk-averse. Leadership hesitates longer.

The root causes remain untouched.

Cloud data migration is often uncomfortable precisely because it is honest.

It replaces implicit trust with explicit validation. It turns silent failure modes into visible discrepancies. It forces organizations to confront risks that already exist.

CTOs who understand this do not ask whether the migration is “causing problems.”

They ask whether the migration is revealing the problems worth fixing.

That distinction determines whether visibility becomes a setback—or a turning point.

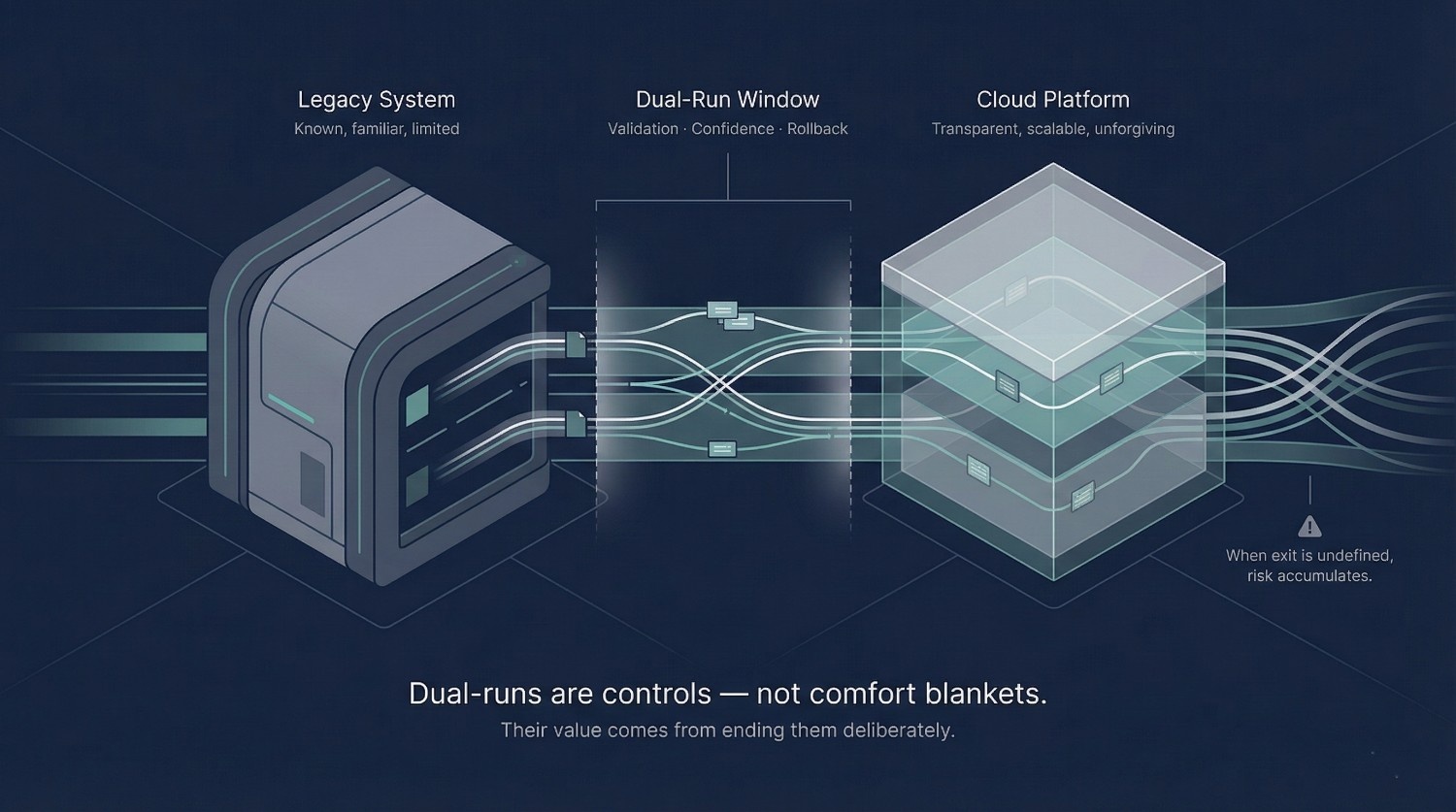

Dual-Run Strategy

Running legacy and cloud systems in parallel is one of the most common—and most misunderstood—patterns in cloud data migration. Dual-runs are often framed as a safety mechanism, a way to reduce risk while confidence builds.

They can do that.

They can also quietly become one of the biggest sources of long-term risk.

The difference lies in how deliberately they are designed, governed, and exited.

Why Dual-Runs Are Necessary

Used correctly, dual-runs are a temporary control–not a long-term comfort blanket.

They exist for three legitimate reasons:

- Validation

Comparing outputs between old and new systems surfaces discrepancies early, when fixes are still cheap. It replaces theoretical confidence with observed correctness. - Confidence building

Stakeholders do not trust new platforms because they are modern. They trust them because results are consistent over time. Dual-runs allow trust to accumulate gradually rather than being demanded at cutover. - Rollback safety

If a critical issue emerges after partial adoption, the organization needs a credible way to fall back without chaos. Knowing rollback is possible enables decisive forward movement.

In this form, dual-runs can reduce uncertainty. They turn unknown risk into observable signals.

How Dual-Runs Quietly Become Permanent

The problem is not that dual-runs exist. It is that they often never end.

This tends to happen when three conditions are missing:

- Fear of cutover

Leadership hesitates to accept visible responsibility for switching the source of truth. Risk is deferred rather than decided. - No success criteria

Teams cannot articulate what “good enough” looks like. Validation becomes open-ended. Perfection is implied but never defined. - No executive deadline

Without a date that forces a decision, dual-runs default to continuation. Temporary safety becomes permanent architecture.

As time passes, the costs often compound:

- Logic diverges between systems

- Fixes land unevenly

- Engineers support two platforms

- Costs double

- Trust erodes as numbers drift subtly out of sync

At that point, the dual-run is no longer mitigating risk; it is amplifying it.

CTO-Level Guidance

For CTOs, the question is not whether to use dual-runs—but how to constrain them.

Dual-runs help when:

- They are explicitly time-boxed

- Exit criteria are defined upfront

- Discrepancies are investigated, not explained away

- Leadership commits to a decision point

Dual-runs harm when:

- They exist “until everyone is comfortable”

- No one owns the cutover decision

- Validation has no finish line

- They become a substitute for leadership judgment

How to time-box them safely:

- Define measurable acceptance criteria (not perfection)

- Set a cutover window before validation begins

- Assign a single accountable decision-maker

- Treat extension as an exception that requires justification

The goal of a dual-run is not to eliminate risk. It is to convert risk into evidence—and then act on that evidence.

A well-run dual-run typically shortens migration risk exposure.

A poorly governed dual-run can extend it indefinitely.

CTOs who understand this do not ask, “Are we confident enough yet?”

They ask, “Have we learned enough to decide?”

That question—and the willingness to answer it—is what determines whether dual-runs protect the migration or quietly undermine it.

Risk visibility at the executive level

CTOs should receive:

- Clear risk summaries

- Decision points

- Tradeoff explanations

- Escalation paths

If risks are buried in engineering tickets, the engagement is mis-structured.

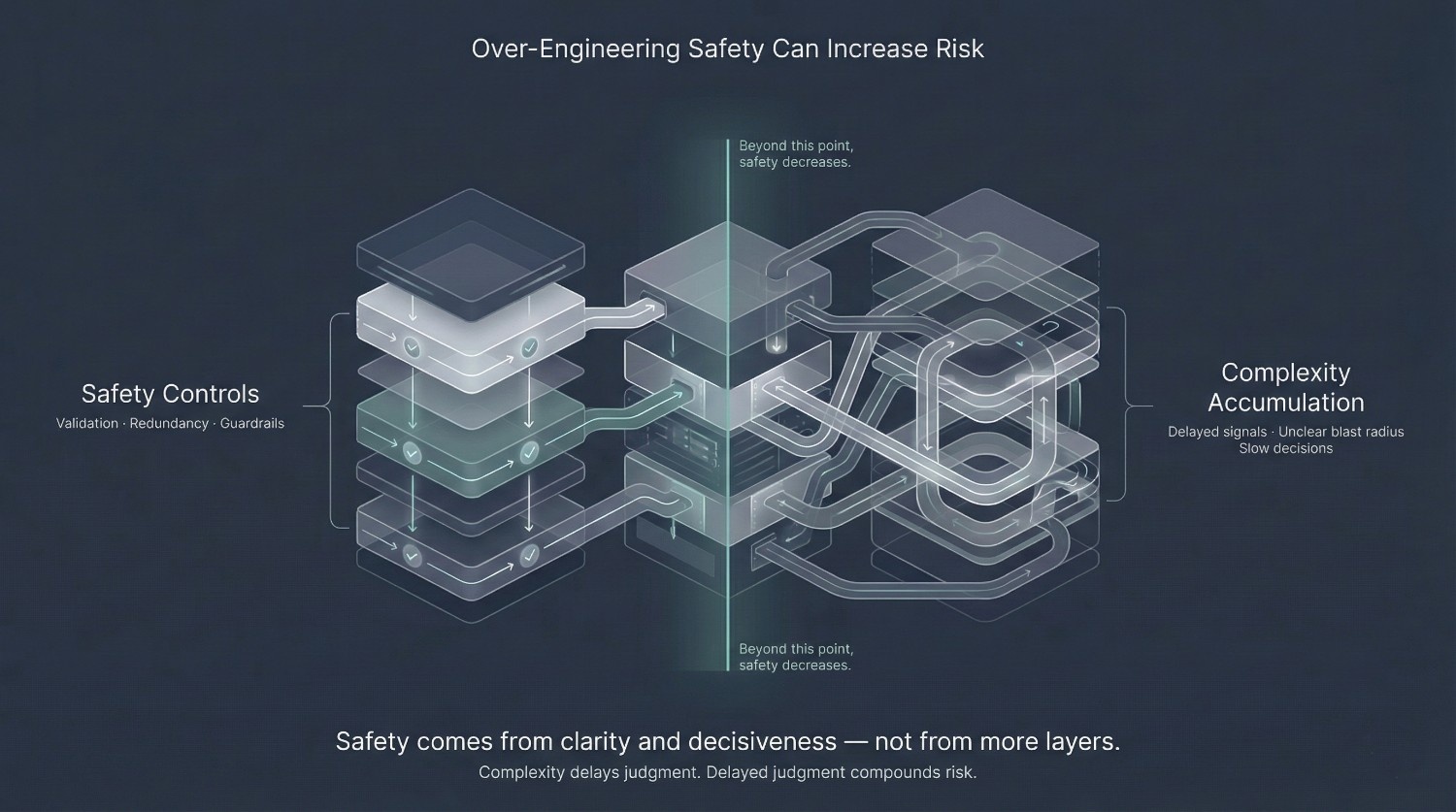

The Hidden Risk of Over-Engineering Safety

When CTOs sense risk in cloud data migration, the instinctive response is often to add more controls.

More validation.

More pipelines.

More safeguards.

Each addition feels responsible. Collectively, they can make the system less safe rather than more.

Over-engineered safety can create complexity that outpaces the organization’s ability to reason about it.

How Over-Engineering Safety Shows Up

In risk-averse migrations, certain patterns often emerge:

- Excessive validation layers

The same checks are implemented at ingestion, transformation, and reporting—each slightly different, each with its own failure modes. - Overlapping pipelines

Multiple paths moving the same data “just in case,” leading to divergence rather than redundancy. - Redundant transformations

Logic duplicated across systems to preserve backward compatibility, even after it should have been retired. - Slow feedback loops

Validation processes that take days or weeks to surface issues, by which time context is lost and fixes are harder.

None of these mechanisms are wrong individually. The danger is that they accumulate without a clear model of what risk they are actually reducing.

Why “More Checks” ≠ “More Safety”

Safety is not primarily a function of the number of controls. It is a function of clarity and responsiveness.

Over-engineered systems often fail in subtle ways:

- Engineers stop trusting alerts because too many fire

- Teams hesitate to change logic because the blast radius is unclear

- Validation becomes a bottleneck instead of a signal

- Issues are detected late, after multiple layers have already propagated bad data

In these environments, correctness often becomes harder to verify, not easier. The system grows defensive—but brittle.

What looks like caution is often fear encoded into architecture.

The Risk CTOs Miss

One hidden risk of over-engineering safety is decision avoidance.

Each additional check defers the moment when someone must decide:

- Is this discrepancy acceptable?

- Is this good enough to cut over?

- Is the residual risk lower than staying put?

Instead of confronting these questions, organizations build layers that postpone them. Complexity increases. Momentum slows.Over time, the migration becomes too fragile to change and too expensive to abandon.

Cloud data migration does not require maximal safety controls. It requires appropriate safety.

CTOs who lead successful migrations resist the urge to eliminate uncertainty through complexity. They design systems that surface risk quickly, clearly, and early—then pair that visibility with decisive action.

Safety comes from understanding risk, not burying it under layers of checks.

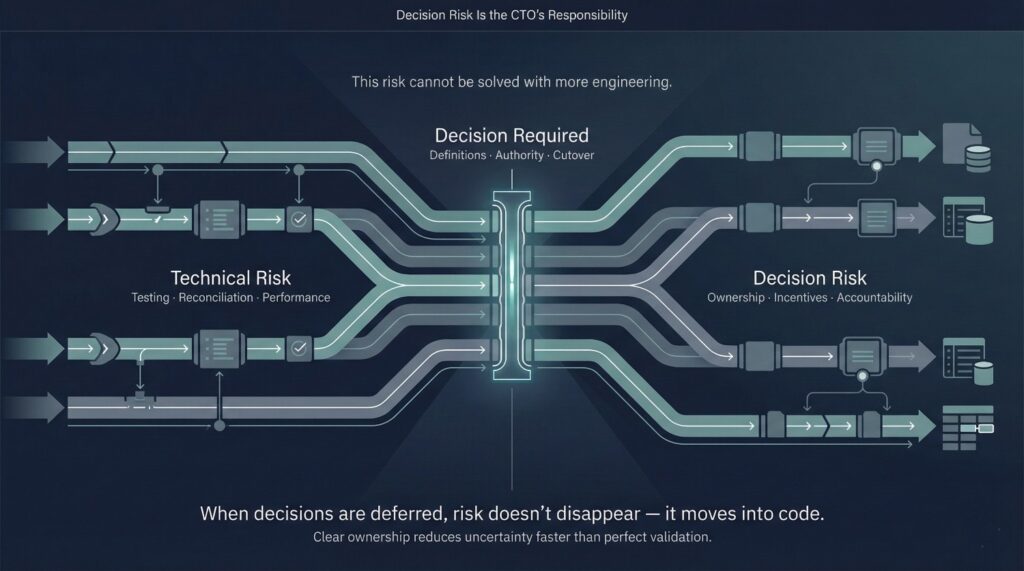

Decision Risk

Among all the risks in cloud data migration, one stands apart—because it cannot be fully mitigated with better tooling, more testing, or stronger engineering discipline.

Decision risk exists wherever progress depends on choices that materially affect incentives, accountability, or power. And those choices cannot be delegated entirely to engineers.

Some Risks Require Executive Decisions

Certain questions surface in most migrations, regardless of industry or stack. They look technical on the surface—but they are not.

Examples include:

- Metric definitions

What exactly counts as “active,” “churned,” or “converted”? Which edge cases matter—and which do not? - Revenue numbers

Which system is authoritative when billing, finance, and sales disagree? Which adjustments are allowed—and by whom? - Customer truth sources

When multiple systems claim to represent the customer, which one wins? And what happens to the others?

These decisions affect reporting, forecasting, compensation, and strategy. They create winners and losers. They cannot be reliably resolved through consensus or experimentation alone.

They require someone with organizational authority to decide—and to absorb the consequences of that decision.

What Happens When CTOs Stay Too Far Removed

When CTOs or executive sponsors remain distant from these decisions, the burden shifts downward.

Engineers are left to navigate ambiguity they cannot resolve:

- Endless debates

Teams revisit the same questions repeatedly, hoping clarity will emerge organically. - Rewritten logic

Transformations are adjusted, reverted, and re-adjusted to accommodate competing interpretations. - Delayed launches

Cutovers slip because “alignment isn’t there yet,” even though no further data will resolve the disagreement.

This is not primarily an execution failure. It is a leadership vacuum.

Engineers often respond rationally by minimizing exposure: duplicating logic, deferring decisions, and keeping dual systems alive. These actions reduce personal risk—but increase systemic risk.

Clear Decision Ownership as a Risk-Reduction Tool

One of the most effective ways to reduce migration risk is not technical at all. It is explicit decision ownership.

This means:

- Naming who decides when definitions conflict

- Clarifying which decisions require executive sign-off

- Defining when “good enough” is sufficient to move forward

- Making it safe to decide imperfectly—but decisively

When decision ownership is clear, uncertainty typically shrinks. Engineers can build with confidence. Validation becomes directional. Dual-runs end on time.

Most importantly, risk becomes owned, not diffused.

Decision risk is unavoidable in cloud data migration. What is optional is whether it is faced directly—or quietly pushed into code, where it becomes harder to see and harder to unwind.

CTOs who engage at the decision layer generally do not slow migrations.

They unblock them.

And in doing so, they turn one of the most dangerous risks into one of the most powerful levers for success.

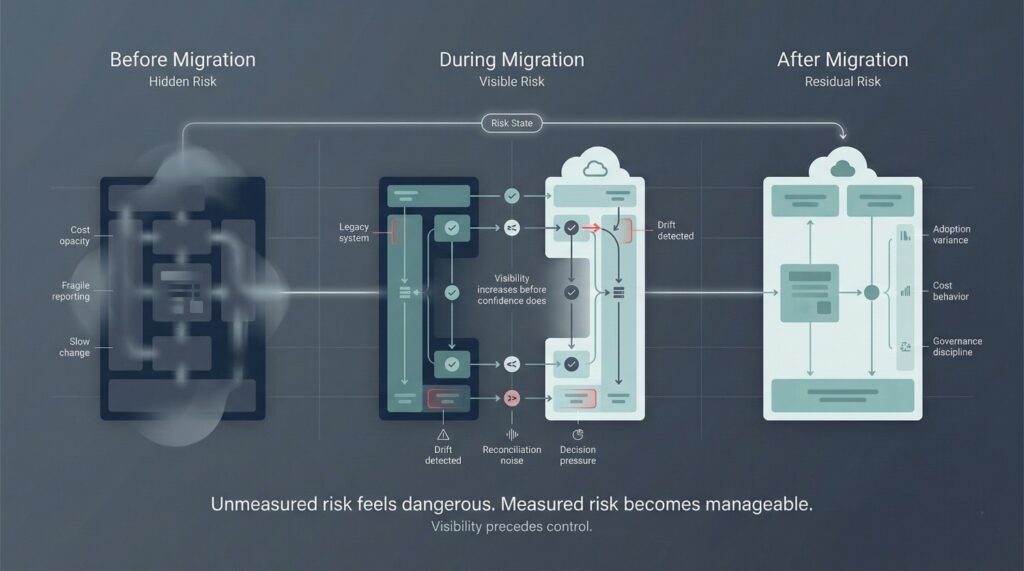

Measuring Risk Before, During, and After Migration

One reason cloud data migration risk feels abstract is that it is rarely measured consistently over time. Risk is discussed in meetings, escalated emotionally, and debated philosophically—but often not tracked as a changing condition.

For CTOs, this is a missed opportunity.

Risk is not static in complex migration programs. It evolves across phases of the migration. When measured consistently, it becomes visible, comparable, and actionable—rather than something teams argue about qualitatively.

What Risk Looks Like Before Migration

Before migration begins, risk already exists—even if it is normalized.

Common pre-migration risk signals include:

- Cost opacity

Teams cannot explain why queries cost what they do, which workloads drive spend, or where inefficiencies hide. Spend is accepted because it is familiar. - Slow delivery

New metrics take weeks to define. Changes ripple unpredictably. Engineers hesitate to touch brittle pipelines. - Fragile reporting

Dashboards break quietly. Numbers require manual reconciliation. Trust depends on people rather than systems.

These risks often feel tolerable because they appear stable. But stability is not safety—it is stagnation.

A key CTO mistake is treating the pre-migration state as “low risk” simply because it is known.

Risk Signals During Migration

During migration, risk becomes more visible—and therefore more uncomfortable.

This phase produces signals that are often misinterpreted as failure:

- Drift between systems

Legacy and cloud outputs diverge. This is expected—but without context, it triggers anxiety. - Reconciliation noise

Validation surfaces discrepancies that were never examined before. Teams struggle to separate real issues from historical artifacts. - Stakeholder confusion

Different numbers appear in different places. Confidence wavers. Questions multiply.

These signals do not necessarily mean risk has increased. They mean risk has become observable.

The danger is reacting emotionally—slowing down, adding complexity, or deferring decisions—rather than using these signals to guide action.

Risk After Migration

Risk does not disappear at cutover. It changes form.

Post-migration risk commonly shows up as:

- Adoption failure

Teams continue using old reports, spreadsheets, or shadow systems. The platform exists but is not trusted. - Cost spikes

Elastic systems expose inefficient usage patterns. Without governance, spend grows faster than value. - Underutilized platform

The migration succeeds technically, but the organization fails to extract new capabilities. The platform becomes expensive infrastructure rather than a strategic asset.

These risks are particularly dangerous because they often emerge after leadership attention has moved on.

What CTOs Should Insist on Measuring

To manage risk deliberately, CTOs should insist on a small, consistent set of indicators tracked across all phases.

At a minimum:

- Error rates

How often data quality issues surface—and whether that rate is trending down. - Time to detection

How quickly problems are discovered after they occur. Faster detection means lower impact. - Cost predictability

Not just total spend, but variance. Predictable cost is safer than cheaper-but-volatile cost. - Business adoption metrics

Which teams use the new platform as their primary source of truth—and which do not.

These metrics do not eliminate risk. They help contextualize it.

When risk is measured, it becomes discussable without panic. Decisions become evidence-based. Leadership confidence improves—not because uncertainty is gone, but because it is understood.

CTOs who measure risk treat cloud data migration as a controlled system, not a leap of faith.

They replace fear with feedback—and that shift often reduces risk more effectively than additional layers of process or tooling.

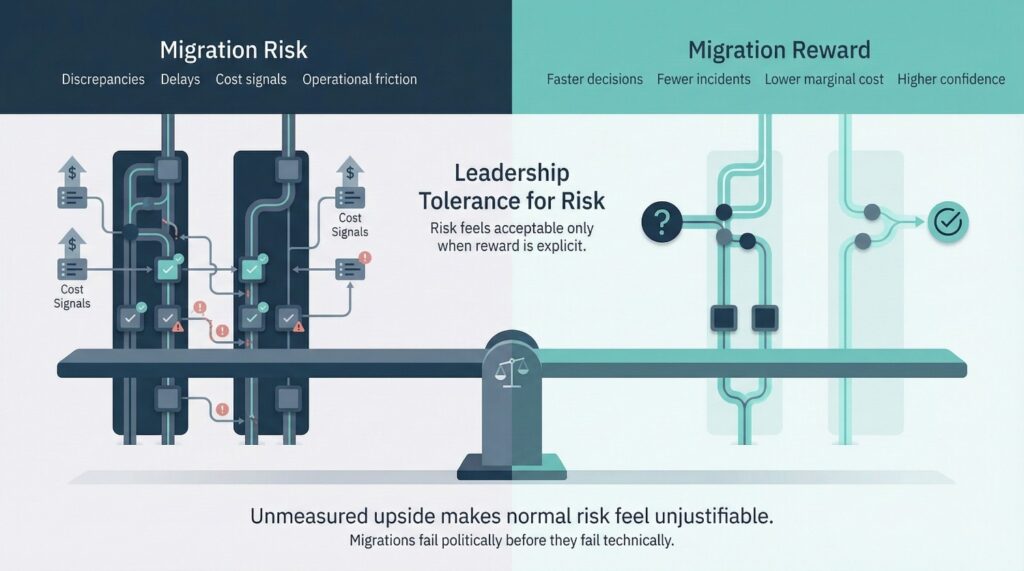

Risk vs Reward

When CTOs say, “We can’t really quantify the gains from this migration,” it is often framed as intellectual honesty.

In practice, it is often a warning sign.

Cloud data migration always carries risk. When the upside is undefined or unmeasured, leadership has little reason to tolerate that risk—and visible issues are more likely to feel unjustified.

Why Migrations Without ROI Narratives Feel Like Failures

Risk is contextual. A migration that introduces disruption is acceptable when its benefits are understood. The same disruption feels reckless when value is vague.

Without a clear reward narrative:

- Every discrepancy looks like regression

- Every delay feels wasteful

- Every cost increase triggers concern

- Every incident erodes confidence

Even a technically successful migration can be perceived as a failure if leadership cannot articulate what was gained.

This is why migrations often stall politically long before they fail technically.

Typical Gains CTOs Can Measure

Most organizations underestimate how measurable migration benefits actually are. While not everything can be quantified precisely, enough can to anchor confidence.

Common gains include:

- Faster analytics cycles

Time from question to answer drops—from weeks to days, or days to hours. This is directly observable and highly valuable. - Reduced incident load

Fewer broken dashboards, fewer emergency reconciliations, fewer late-night firefights. Engineering effort shifts from recovery to improvement. - Lower marginal query cost

Even if total spend grows, the cost of answering each additional question often falls materially. - Better decision confidence

Fewer meetings spent arguing about numbers. More time spent acting on them. This is qualitative—but consistently felt by leadership.

These gains do not require perfect attribution. They require baseline comparison and honest tracking.

Why Not Quantifying Gains Often Increases Leadership Anxiety

Unquantified benefit creates asymmetry.

Risk is visible.

Cost is visible.

Effort is visible.

Value is not.

In that vacuum, leadership fills the gap with concern. They become more risk-averse, more skeptical, and more likely to intervene late—often in ways that slow or derail the migration.

Ironically, avoiding quantification to appear cautious often produces the opposite effect: increased anxiety and reduced tolerance for uncertainty.

Cloud data migration does not require a flawless ROI model in practice. It requires a credible one.

When CTOs can articulate what the organization is gaining—and how those gains offset risk—migration becomes a strategic decision rather than a technical gamble.

Without that narrative, even modest risk can feel unjustifiable.

In the final sections, we’ll focus on how CTOs can actively shape risk—by deciding where to apply discipline, where to accept imperfection, and where to move decisively.

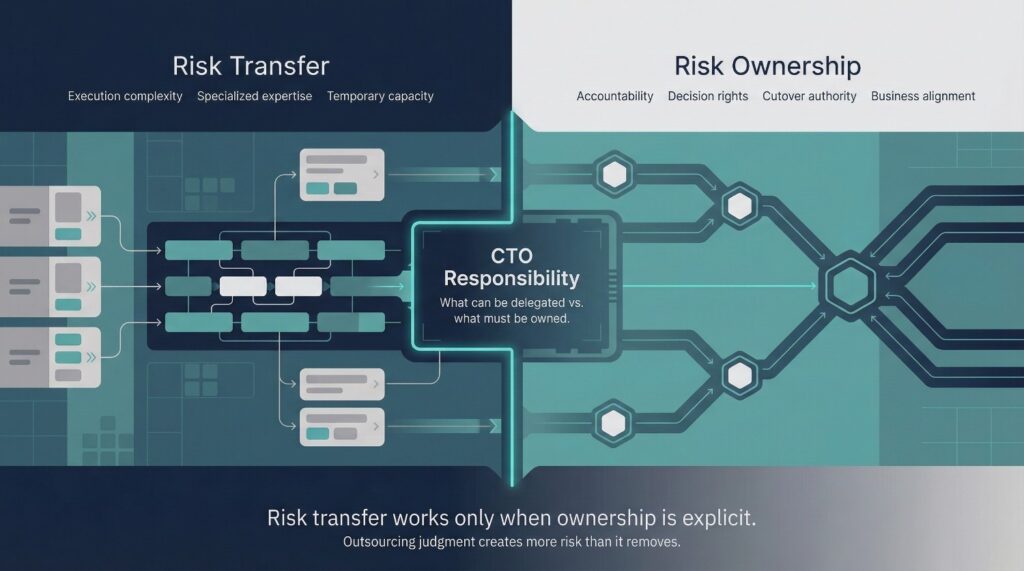

Risk Transfer vs. Risk Ownership

As cloud data migration complexity grows, CTOs often ask a reasonable question:

Which risks can we delegate—and which must we own ourselves?

Understanding this distinction is critical. Some migration risks can be reduced or transferred through tooling, vendors, and external support. Others are inherently non-transferable—and attempts to outsource them often make outcomes worse, not better.

What CTOs Should Own Directly

Certain risks sit squarely within the CTO’s mandate and cannot be pushed downstream without significant consequence.

These include:

- End-to-end accountability

Someone must be answerable for the migration’s outcome—not just its execution. This accountability should not be fragmented across teams or contracts. - Decision framing

Determining which trade-offs matter, which risks are acceptable, and which require escalation is a leadership responsibility. - Cutover authority

The moment when the organization commits to the new platform as the source of truth requires executive ownership. No external party can credibly make that call on the organization’s behalf.

When CTOs retain ownership here, migration risk becomes bounded and intentional rather than diffuse and reactive.

What Can Be Transferred

Other risks are well-suited for transfer—when done deliberately.

Examples include:

- Execution complexity

Building pipelines, implementing validation, handling scale, and managing tooling details can be supported by experienced vendors or consulting partners. - Specialized expertise

Platform-specific knowledge, migration patterns, and failure-mode awareness are often faster to acquire externally than to build internally from scratch. - Capacity risk

Temporary augmentation reduces burnout and prevents migration work from being perpetually deprioritized behind feature delivery.

This kind of risk transfer works best when internal ownership is clear upfront. External support amplifies clarity—it cannot replace it.

What Cannot Be Outsourced

Some risks cannot be transferred without introducing new ones.

Specifically:

- Accountability

If outcomes are unclear, no vendor can be held responsible in a meaningful way. Accountability must remain internal. - Decision rights

External teams can inform decisions—but they cannot resolve political trade-offs or choose winners between competing business definitions. - Business alignment

Only internal leadership can align migration outcomes with strategy, incentives, and organizational priorities.

When organizations try to outsource these responsibilities, migrations often slow. Decisions stall. Engineers and partners wait for direction that never comes.

Cloud data migration succeeds when risk transfer is used to support risk ownership rather than to avoid it.

CTOs who understand this distinction create migrations that are both safer and faster. They leverage external expertise where it reduces execution risk, while retaining ownership where judgment, authority, and alignment are required.

This balance is not about control. It is about clarity.

And clarity is among the most effective risk-reduction tools a CTO has.

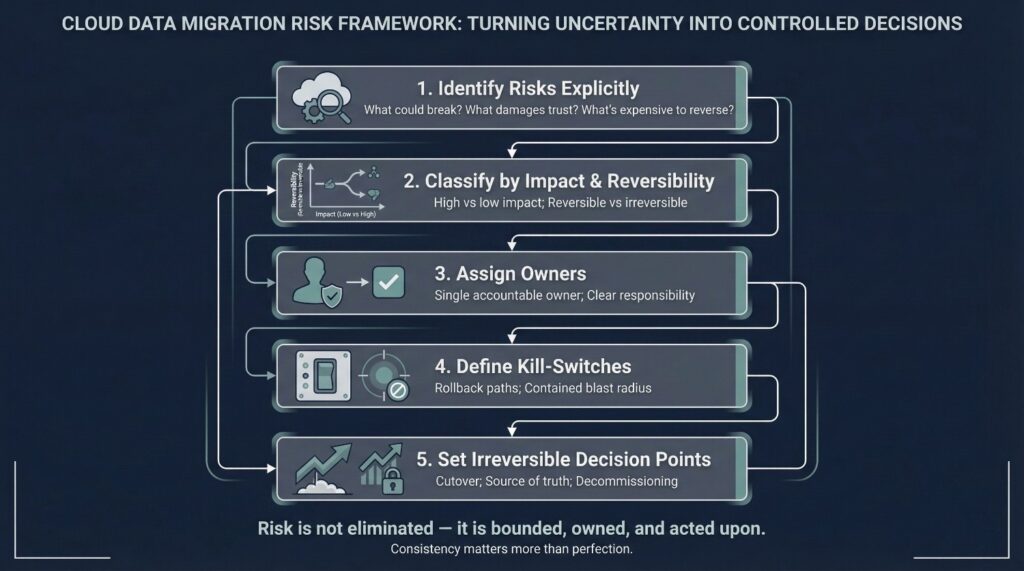

A Practical Risk Framework for CTOs

Risk-aware cloud data migration does not necessarily require complex governance models or heavyweight processes. It requires consistency, visibility, and decisiveness.

Many effective CTOs use a simple, repeatable framework that turns abstract risk into something the organization can reason about and act on.

Identify Risks Explicitly

The first step is making risk discussable.

Instead of treating risk as an ambient concern, successful migrations name it directly:

- What could break?

- What would damage trust?

- What would be expensive to reverse?

- What assumptions are we making?

This forces the organization to separate real risk from discomfort. Risks that remain unnamed often reappear later as surprises.

Classify by Impact and Reversibility

Not all risks are equal.

Each identified risk should be classified along two dimensions:

- Impact — If this goes wrong, how bad is it?

(Minor inconvenience vs. financial exposure vs. customer harm) - Reversibility — If it goes wrong, can we undo it easily?

(Config change vs. data rewrite vs. reputational damage)

This classification guides behavior. High-impact but reversible risks can be taken earlier. Low-impact but irreversible risks deserve caution. Treating all risks the same often leads to paralysis.

Assign Owners

Every meaningful risk benefits from having a clear owner rather than a committee.

Ownership means:

- Monitoring the risk

- Raising signals early

- Recommending action

- Being accountable for follow-through

Without ownership, risks float between teams until they materialize. With ownership, they become manageable—even when uncertainty remains.

Define Kill-Switches

CTOs should insist on kill-switches for major migration steps.

A kill-switch answers a simple question:

If this goes wrong, how do we stop the damage?

Examples include:

- Feature flags that revert data consumers

- Rollback paths for pipelines

- Traffic gating for critical workflows

Kill-switches often reduce fear. They make risk-taking safer by bounding blast radius. Teams move faster when they know failure is containable.

Set Irreversible Decision Points

Finally, successful migrations define when reversibility ends.

These are moments where the organization commits:

- A source of truth is declared

- A legacy system is decommissioned

- Dual-run ends

- Ownership shifts permanently

Avoiding these moments feels safer—but it can extend risk indefinitely. Defining them early creates focus and urgency.

This framework does not eliminate uncertainty. It channels it.

CTOs who apply it consistently can turn cloud data migration from a high-anxiety endeavor into a sequence of controlled, intentional steps.

Risk stops being something to fear—and becomes something the organization knows how to manage.

Why the Best Migrations Feel “Boring”

Many of the most successful cloud data migrations rarely make good stories.

There are no war rooms.

No heroic recoveries at 3 a.m.

No dramatic rollbacks announced in all-hands meetings.

From the outside, they can look almost… uneventful.

That is not a lack of ambition. It is a strong signal that risk was handled correctly.

No Fire Drills

In struggling migrations, risk often announces itself loudly—through outages, broken reports, and emergency escalations. In successful ones, risk is surfaced early and often addressed before it becomes urgent.

Issues still occur. They just appear as:

- Controlled discrepancies

- Expected validation failures

- Known trade-offs being exercised

Instead of fire drills, there are routine adjustments. That quiet is intentional.

No Heroic Recoveries

Heroics are often celebrated in engineering culture. In migrations, they are often a warning sign.

When success depends heavily on individuals working nights and weekends to “save” the system, it usually means risk was allowed to concentrate too late. The system relied on people instead of process.

Boring migrations distribute responsibility:

- Decisions are made before crises

- Kill-switches are tested, not improvised

- Ownership is clear long before things go wrong

The absence of heroics means the system—not the individuals—is doing the work.

No Dramatic Rollbacks

Rollbacks are not inherently failures. But dramatic, last-minute rollbacks usually indicate that confidence was assumed rather than earned.

In boring migrations:

- Dual-runs end on schedule

- Cutover criteria are met gradually

- Rollback remains theoretical, not necessary

When rollback plans exist but are never used, it often means risk was converted into evidence early—and acted on decisively.

Quiet Confidence

What replaces drama is something far more valuable: confidence.

- Engineers trust the pipelines

- Stakeholders trust the numbers

- Leadership trusts the trajectory

This confidence is not blind. It is built through validation, measurement, and clear decision-making. Nothing feels rushed. Nothing feels fragile.

Progress continues—not because people are pushing harder, but because friction has been removed.

Why Boring Is the Highest Signal of Success

Boring migrations are rarely lucky. They are the result of:

- Explicit risk ownership

- Measured trade-offs

- Time-boxed uncertainty

- Leadership willing to decide

When cloud data migration feels boring, it usually means risk has been transformed—not eliminated, but managed so effectively that it no longer demands attention.

For CTOs, that is the real goal.

Not a perfect migration.

Not a risk-free one.

But one so well-governed that success feels almost ordinary.

Final Thoughts

Cloud data migration does not reliably reward certainty.

It rewards judgment.

The CTOs who succeed are not the ones who attempt to eliminate risk. They are the ones who are willing to understand it, name it, and act in spite of it.

What Cloud Migrations Actually Require

Successful migrations demand a specific kind of leadership posture:

- Informed risk acceptance

Knowing which risks are temporary, which are structural, and which are worse than the status quo—and accepting some of them deliberately. - Clear leadership

Not constant oversight, but visible ownership at the moments where trade-offs matter. - Structured decision-making

Decisions framed by impact, reversibility, and timing—not by comfort or consensus.

These qualities do not remove uncertainty entirely. They prevent it from spreading unchecked.

Zero Risk Is a Myth

The belief in zero risk is comforting—and dangerous.

It encourages delay instead of decision.

Complexity instead of clarity.

Duplication instead of commitment.

Organizations that pursue zero risk do not necessarily become safer. They often become slower, more fragile, and less honest about the risks they are already carrying.

The Real Goal: Controlled, Visible, Intentional Risk

The CTO’s job is not to promise safety.

It is to create conditions where risk is bounded, visible, and owned.

When risk is intentional:

- Teams move with confidence

- Leadership stays aligned

- Progress compounds instead of stalling

Cloud data migration often succeeds not because everything is known—but because enough is known to act.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

In practice zero risk is a myth. Every production data system already carries risk—usually hidden. Cloud data migration typically does not introduce new categories of risk; it changes their shape and visibility. The goal is not elimination, but controlled, intentional risk.

Because risk avoidance often leads to indecision. Extended dual-runs, endless validation, and delayed cutovers increase complexity, cost, and fragmentation. This can create more systemic risk than a bounded, well-timed decision would.

Organizational risk, in many cases. While technical and operational risks are real, many failed migrations collapse due to unclear ownership, stalled decisions, competing priorities, and cultural resistance rather than broken pipelines alone.

Often—but typically only temporarily. Dual-runs are useful for validation and confidence-building, but dangerous if left open-ended. Without exit criteria and executive deadlines, they often become permanent risk amplifiers.

At a minimum:

- Error rates and data incidents

- Time to detection and resolution

- Cost predictability (not just spend)

- Business adoption of the new platform

Unmeasured risk creates anxiety and erodes confidence.

Because risk becomes visible while value does not. When gains are not articulated—faster analytics, fewer incidents, lower marginal cost—every issue feels unjustified, even if the migration is technically successful.

Often boring. No fire drills, no heroics, no dramatic rollbacks. Quiet confidence replaces urgency because risk is surfaced early, decisions are made on time, and ownership is clear.